AN email from Jimmy Taylor in Coxhoe: “I can remember in the late 50s or early 60s when Sunderland were playing Leicester City in a league game at Roker Park.

“The first team goalkeeper was injured before kick-off and a 16-year-old lad had to play in goal for Sunderland. I think his name was Foster.

What happened to him?”

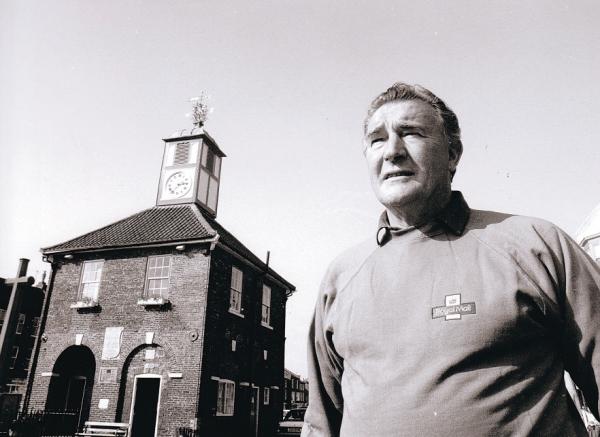

It was August 22 1964, first day of the season, the match ended 3-3 and Derek Forster was just 15 years and 184 days old, still the youngest-ever top flight footballer.

He’s now 61, still in Sunderland, happy for the ten thousandth time to talk about the day he became Monty’s double.

What’s much less widely known is that, three years ago, Derek Forster lost his left eye through cancer.

“It changes your whole life,”

he reflects. “You either jump off the bridge or you tell yourself to get on with it.

“It makes you realise that it doesn’t matter how hard you train, or how careful you are about what you eat, it’s someone else who’s calling the shots.”

He’s since retired after 30 years with the city council’s leisure department. “We presumed that we’d do all sorts when we retired and then I realised that I mightn’t even have got that far.

“Now we don’t presume anything. I’ve changed a lot; if that tumour had spread I was a goner. Now every day is a Sunday.”

HE WAS a Newcastle lad, not a Wearsider, a promising centre forward and St James’ Park regular summoned for trials with the city’s under- 11s.

“One of the goalies didn’t turn up, so they asked me to play there. That’s how much they thought of as a centre forward.

“I’d honestly never kept goal in my life, not even in the back street, but I had a blinder. Caught every ball.

After that, I never played anywhere else.”

He appeared nine times for England schools in a squad that included Trevor Brooking, Colin Todd, Colin Suggett and Joe Royle, was coveted by every first division club in the land, signed for Sunderland a month before the start of 1964-65, joined by fellow Newcastle schoolboys Dennis Tueart, Brian Chambers and Paddy Lowry.

You had to be a bit careful, he recalls, admitting you were Geordies playing for Sunderland.

“Times were different, better then. You learned your football on the back streets, or on the field behind the school, none of this academy stuff.

It’s so strict, it’s ridiculous.”

For two weeks of that preseason month he’d been on a family holiday in Blackpool.

He’d trained for just a week, never seen his new team mates play competitively.

Then regular goalkeeper Jim Montgomery broke his arm in training.

Sunderland were between managers. Everyone assumed that the erstwhile Bank of England club would promote Derek Kirby – reserve goalkeeper throughout the previous season – or dip into what remained of the coffers.

Instead they turned to the man who legally remained a Forster child. For Fulwell End read Deep End.

Gordon Banks stood in Leicester’s goal, the crowd 45,000. The youngster, said the following Monday’s Echo had the agility of a panther, was bursting at the seams with talent, won every heart.

Subsequent issues generated fierce debate over whether the youngster was being subjected to trial by ordeal. He himself insists not.

“To me the Leicester match was just another game of footy, which was great. I’d played in front of 99,000 at Wembley, had dealings with you boys. I could handle it.”

George Mulhall scored two, Nick Sharkey the other.

“Derek’s wonderful prospect.

From what I could see he didn’t make a single mistake,”

said Banks.

“A great game. If he goes on like this he’ll have an exceptional future,” said Roker skipper Charlie Hurley.

Forster played the next few games but in a further eight years at Sunderland managed just 18 in total.

Retrospectively, he regrets not moving on.

“Sunderland were one of the top youth clubs and they were very good to me. I should have left much earlier, seen the signs, but in those days players were genuinely loyal.

You didn’t just ask to leave as soon as you were dropped.

“I decided to stay. It was my mistake. Monty never got injured again for five years, though I tried hard to kick him in training. He was an exceptional goalkeeper.

“It was very similar to Shay Given and Steve Harper at Newcastle. Both very good goalkeepers, but maybe one a bit better than the other.”

His early success had also led to resentments. “It was very difficult for me not to let it go to my head. A lot of people were jealous, people who didn’t even know me.

“You had to be very careful where you went and what you did. because there were people always looking to bring you down.”

Finally he moved to Charlton Athletic, making just nine senior appearances, before Brian Clough took him to Brighton. There he made but three.

“Basically I got a bit cheesed off at Brighton, decided to come home, played locally and in the Over 40s League and got a job with the council.

“I might have been there still, but for what happened with my eye.”

THEY’D sent him to a professor in Liverpool, the top man in Europe. “They tried all sorts to save my eye but unfortunately they couldn’t.

There were people in the same position with a really good attitude; I learned a lot from them.

“You can’t tell I only have eye, it’s so clever what they do.

It’s the same colour exactly.”

Now he plays golf, walks a lot, watches football on television – “I prefer the lower leagues, it’s more genuine” – takes plenty of holidays, always packs a spare eye.

“We thought we’d be bored when we retired but there loads and loads to do, though I still do nowt before 11 o’clock.

“Life’s great. We make the most of it now.”

THERE should have been new pictures of Derek and his wife, but events conspired against. Instead we hear from Derek Jago in Bishop Auckland, his eye drawn to the back page picture in Thursday’s paper of Andy Reid, a Sunderland player of more recent vintage.

“Do you think he’s been modelling himself on The Jolly Fisherman?” asks derek.

Tributes paid to evergreen Allison

MALCOLM Allison was affable, occasionally affluent, eminently quotable. “You get your best experiences from failure,” he once told me. “Optimism is just a cynical pessimism.”

We’d enjoyed two substantial interviews, the first shortly after he became £30,000-a-year manager of Conference side Fisher Athletic – south London – in July 1989.

It was the 39th anniversary, as Kenny Everett reminded his Capital Radio listeners, of Andy Pandy’s television debut.

“I’ve won four leagues already, there’s still time for one or two more,” said the big feller. He didn’t last until Christmas.

The second interview was in a restaurant in Yarm, four years later.

Malcolm was 66, somewhat meretriciously preparing to celebrate the 50th anniversary of his football debut and to start a coaching school in Darlington.

“He could easily be mistaken for 50,”

we wrote. “Pretty good for a chap who thought he’d never reach 30.”

He’d made other Backtrack appearances, too, often in connection with his time at Willington – “I thoroughly enjoyed, it was nice to share success”. On one occasion, he, George Best and Rodney Marsh – an eternal triangle, if ever – had been spotted carousing at McCoy’s, off the A19 near Northallerton.

Though it was among the region’s priciest restaurants, we noted, no expense had been spared. “Allison smoked Romeo and Juliet cigars, Best passed the port, Marsh went through the menu like it was a third division defence.”

Best and Marsh were at the end of a £3,000 a night speaking tour. Allison was an old age pensioner. Malcolm paid.

The two interviews had been linked by Lynn Salton, a Stokesley primary school teacher with whom he lived in Yarm. Scholars Court, truth to tell.

In 1989 she was recovering from a brain tumour that threatened her sight, told just that morning that her driving licence would be returned. He was ecstatic.

Four years later they had a little girl called Gina, not so much the apple of his eye as the veritable orchard. He’d take her to nursery school on the bus.

Malcolm used his pass.

The relationship ended acrimoniously. Whether Malcolm was unlucky in love or love unlucky in Malcolm will have to be one for the historians.

He’d talked of his early days, of how he nearly became a Fleet Street photographer, of the time playing for West Ham when he lost a lung – “I remember lying there thinking I was going to die and there was still £200 I hadn’t spent” – of how he became a professional gambler, won £80,000 in a year, bought a club in London.

His true joy was in coaching, in bringing through kids. He’d been on the same Lilleshall course as Stan Matthews. Stan lasted three days.

Back lunching in Yarm, he’d noticed a traffic warden about to stick a ticket on the photographer’s car. Big Mal, bless him, went outside, gave her a kiss and a cuddle, implored reconsideration.

“I’ll think about it,” she said, The photographer never got his ticket.

The Jolly Fisherman – memorably sub-titled “Skegness is SO bracing” – is history’s most famous railway poster. It was drawn in 1908 by John Hassall, who received 12 guineas for his trouble but had never been to Skeggy and never went until 1936, when a grateful council gave him the “freedom of the foreshore.”

He died, penniless, in 1948.

Andy Reid, bracing himself, may never experience such hardship.

Warburton’s ready for his UFC curtain-raiser

CURT Warburton, that most agreeable young man from Coundon, makes his debut tonight in the UFC mixed martial arts ring, the seriously big time.

Around 200 mates are following him down to the Octogon in London from the former pit village near Bishop Auckland. Paul “Pele” Aldsworth, in charge of arrangements, forecasts that the Saturday night pubs will be empty.

“I’m not saying we’re confident, but we’ve all taken Monday off work because there’s going to be one hell of a party when we got back to Coundon on Sunday.”

Curt, a former Northern League footballer who also played for Coundon Conservative Club in the FA Sunday Cup final at Anfield, has been preparing full-time for the moment at the Wolfslair gym in Widnes.

“I used to dig holes for a living, look out of the window some mornings and wish so hard that I didn’t have to go to work,” he told the column in August.

“I’ve never ever woken up here and wished that I hadn’t to train.”

He fights Spencer “the King” Fisher, an American with 29 UFC bouts behind him. “Spencer’s been going around bad mouthing Curt, saying he’s going to knock him down, ground him and pound him,” says Pele.

“You’d never get Curt doing that. If you saw him in the street, you’d never guess what he did for a living.”

Curt admits he’s the underdog. “I know people are writing me off, but all the pressure’s on him. If I can’t perform on the night, I’ll have to pack in what I love and go back to work.”

MICKEY Little, known otherwise as the Flying Window Cleaner, woke up last Saturday feeling a bit ropy, thus missing his first Over 40s League game for nigh on 20 years. His team, Mill View from Sunderland, were at Trimdon Vets. Beaten 5-0, they also lost their star man with a broken arm.

League secretary Kip Watson rang Mickey to commiserate. “Quite rightly,”

says Kip, “he’d taken himself back to bed.”

ALMOST none of the Over 40s may be senior to 62-year-old John Lee from Belmont, Durham, the referee with the best-known knee support bandage in North-East football.

John, recently named Durham and District Sunday League referee of the year for the third successive season – “the sympathy vote,” he insists – was on the line on Tuesday evening for the STL Northern League match between Chester-le-Street and Whickham.

As usual, too many were standing in the technical area. “If you don’t sit down I’ll kick your a**e,” came the voice of authority.

It worked. “Man management,” said John.

WELL and truly gone to the dogs this time. Rebuked by the Shildon lads at Workington last Saturday, we’re still trying to get right the location of the last Football League ground to double as a venue for greyhound racing. First it was Gateshead, then Chelsea and now – finally – it’s Eastville, home of Bristol Rovers until 1986 and of a dog track for a further 11 years. The greyhounds then ran off to Swindon. Eastville’s now an Ikea.

And finally..

THE two Workington football managers of the 1960s who jointly took their side to an FA Cup final a decade later (Backtrack, October 12) were Joe Harvey and Keith Burkinshaw, with Newcastle United.

Fred Alderton in Peterlee today invites readers to suggest what Kaiser Chiefs’ fan Freddie Maake claims to have invented by removing the black rubber from a bicycle horn.

Cornucopia, the column returns on Tuesday.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here