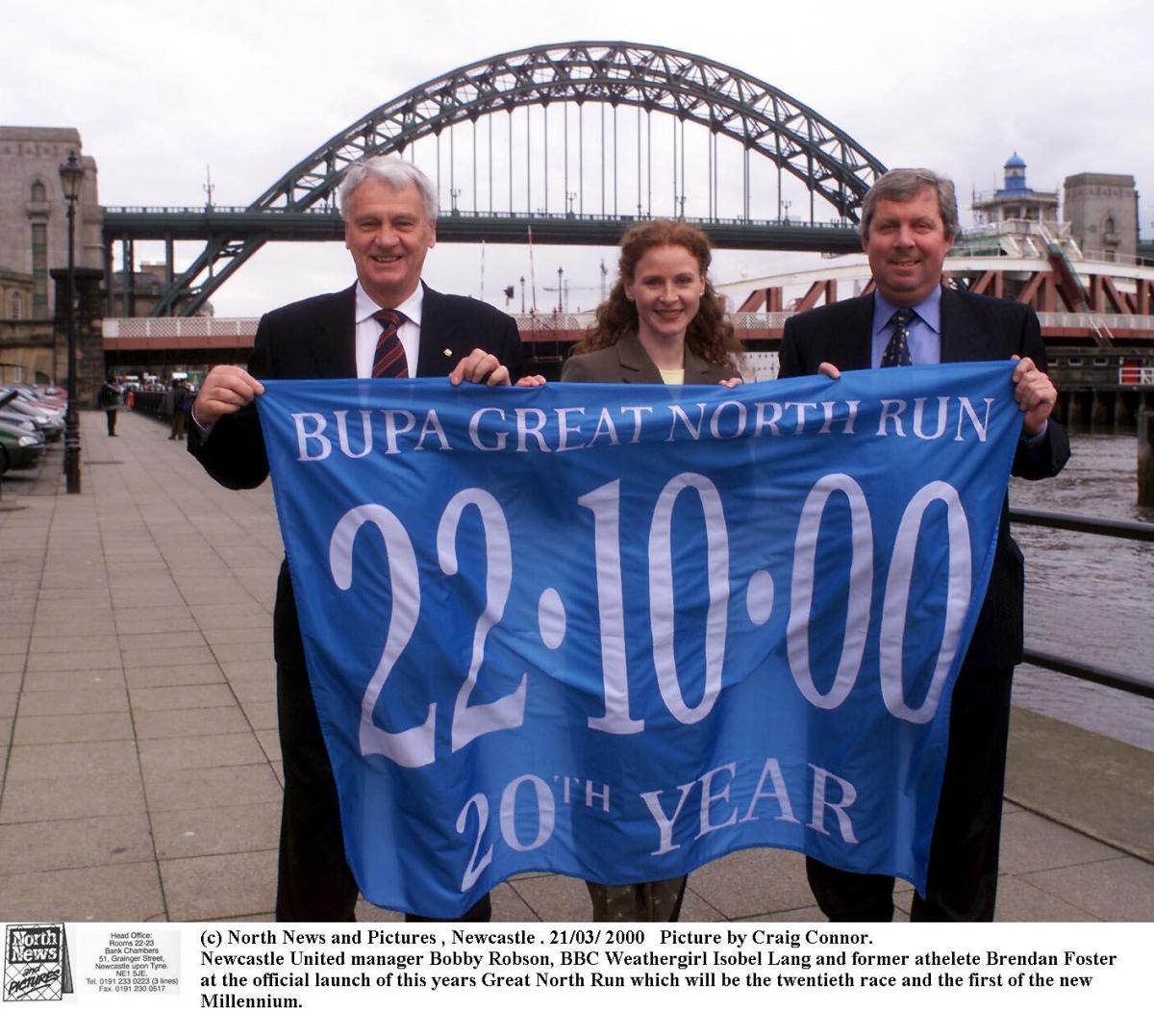

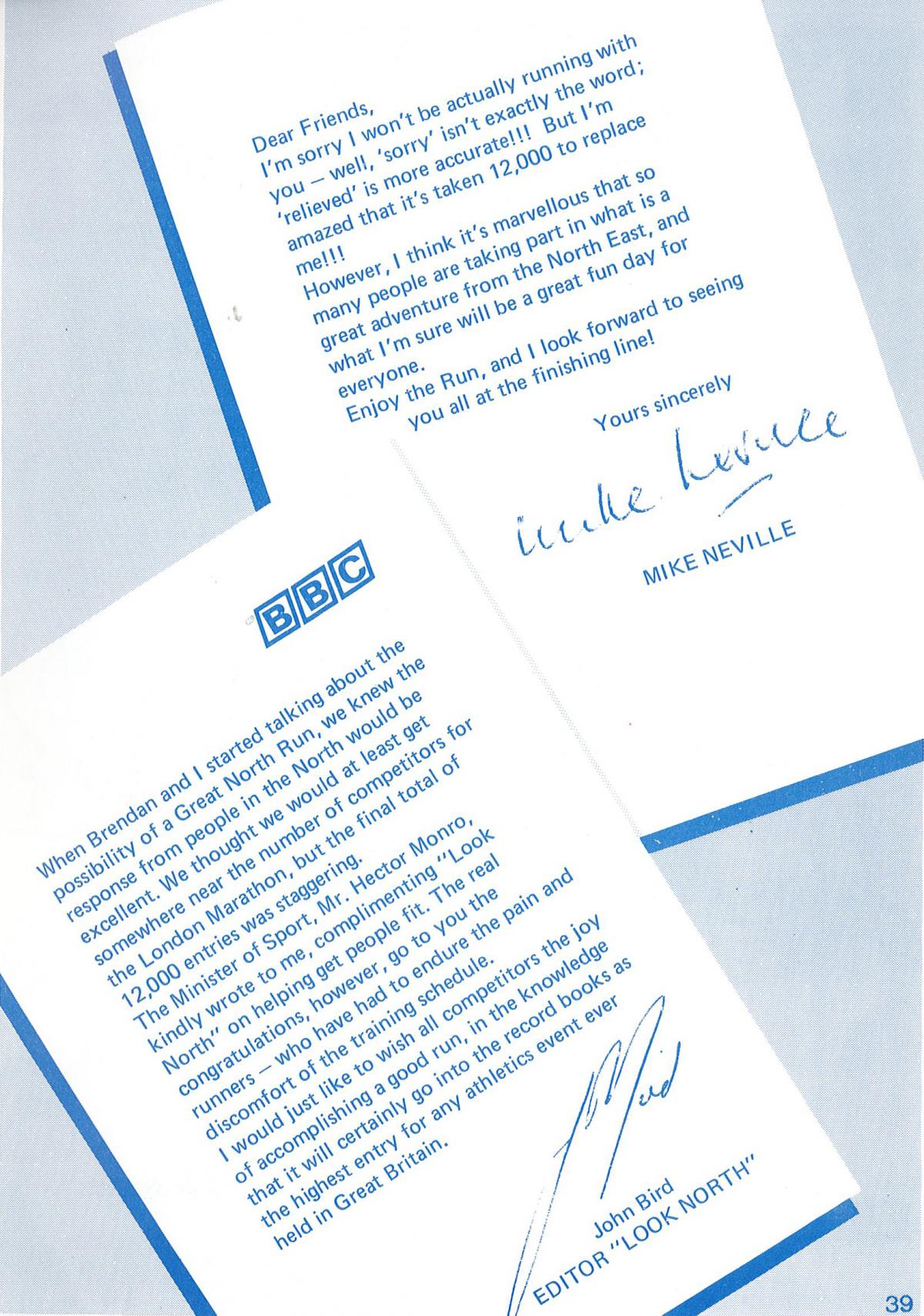

DECEMBER 1980. Brendan Foster, newly-retired as an athlete of Olympic standard, invites four of his fellow Gateshead Harriers for a get together.

Little did they know what they were letting themselves in for as they entered the Five Bridges Hotel. A pint and a sandwich was on the agenda in room 320. The first starting gun for the Great North Run was about to go off.

Some 40 years later, the biggest half marathon in the world is part of the North-East’s fabric. More than that, it’s become a must-do for many: fun runners, club athletes and the world’s elite alike.

“We all got together John Cain, Dave Roberts, Max Coleby, Johnny Trainor and me –and it was right, you do the start, you do the course in the middle, you do the finish, you do the promotion and it went from there. We were all Gateshead Harriers.’’

Coleby recalled: “When we arrived, we didn’t know what it was all about, but you could see in his eyes the enthusiasm he had for the idea.

“When Brendan gets locked on to something it generally happens.”

Foster, with his global standing, looked at the event promotion, dealing with sponsors and the media. Caine, appointed race director, was tasked with finding a route, Roberts managed the start, Coleby had to map and measure the route while overseeing the medical aspect of the event and Trainor had the finish to arrange.

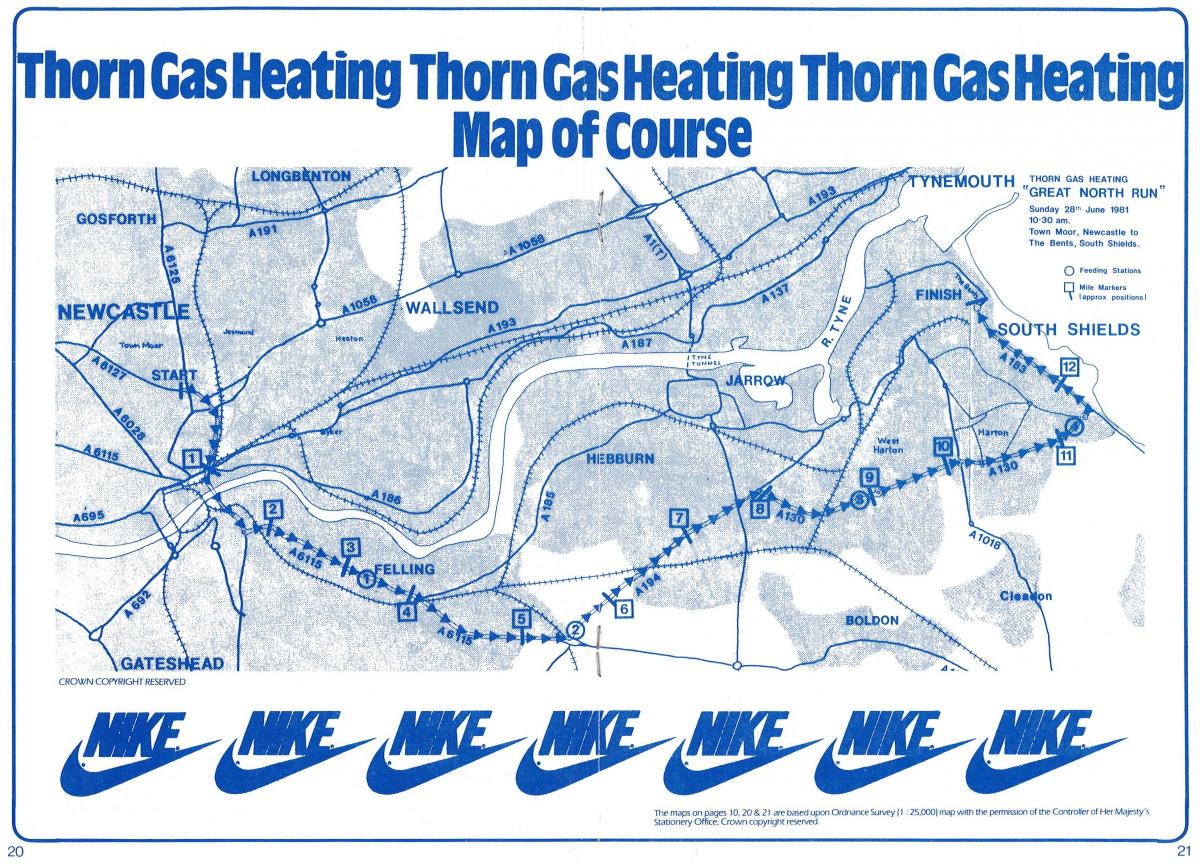

Caine left the hotel, walked to his car and, instead of heading home, decided to drive in different directions to see where 13.1 miles would take him.

Starting at the Tyne Bridge, he first finished north at Morpeth, which had to be ruled out because there was already an established race there. Back to the start, then he ended up at Chester-le-Street; a pronounced hill brought an end to that thought.

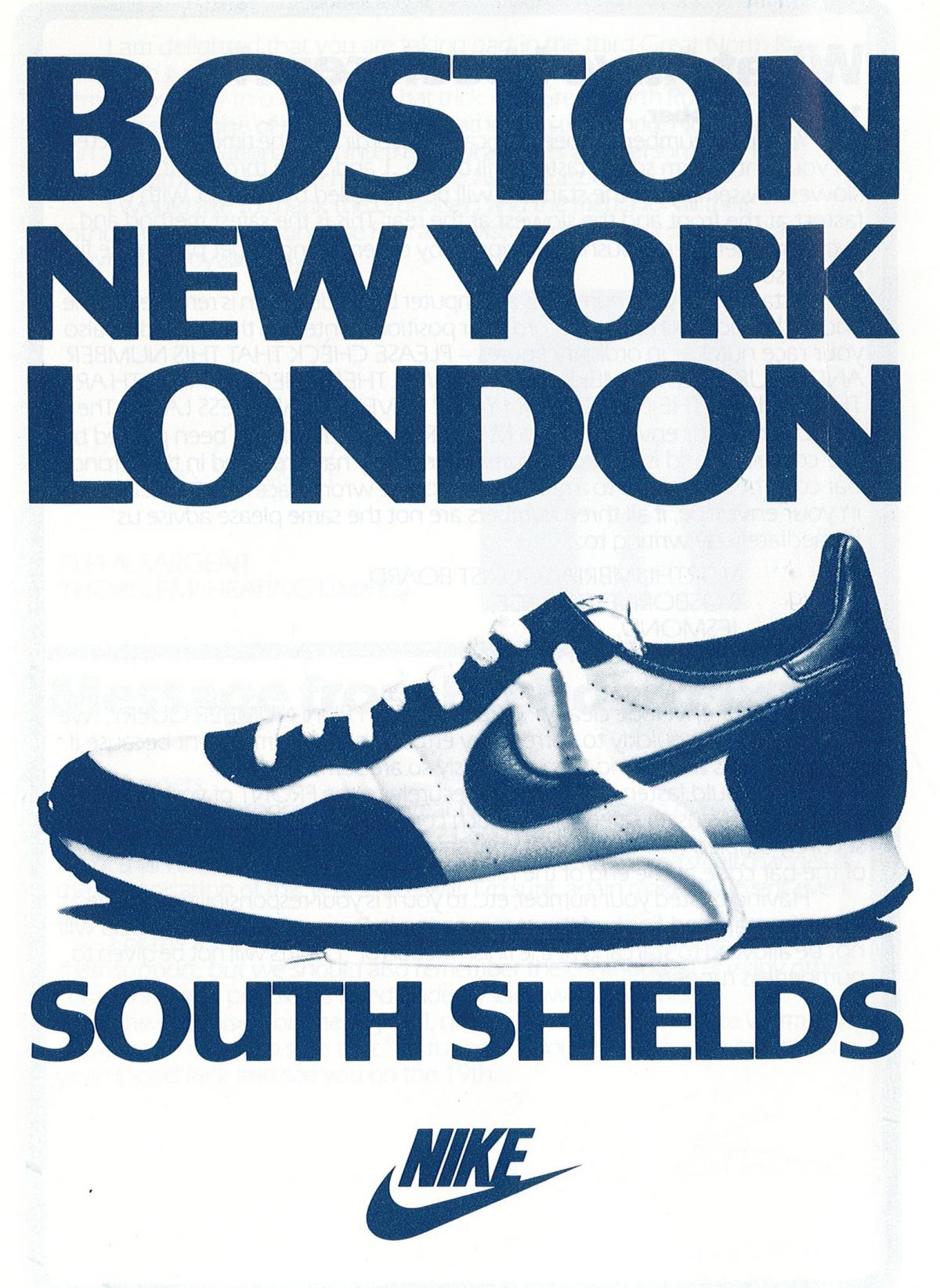

Then he headed east, across to South Shields.

He said: “It didn’t feel right and then I made the dramatic drop to the sea front. The impact hit me. I thought ‘wow.’ I had this big stretch of road ahead of me.”

Having convinced the rest of the team that this was the route, they had to decide on a name.

The Geordie 5000, the Tyne Race or even just the Newcastle-Shields Race had been mentioned.

Instead, drawing on comparisons to the A1, known as the Great North Road, Caine suggested it be named the Great North Run. “Just like that,” he said.

The notion of a North-East event was initiated on the other side of the world. Foster, in training for the Moscow Games, had signed up for the Around The Bays race in Auckland. Thousands of runners took part, and while the running boom was yet to really hit the UK, Foster knew there was scope for it to grow back home.

“I’d ran a big race in New Zealand, 10,000 runners and I’d seen nothing like it,’’ he recalled. “After I retired following the 1980 Olympics I asked about starting an event, in the city and running to the seaside – the same as had happened in Auckland.

“We only ever planned one, the first run and nobody knew what it would be like, what would happen. The biggest race in the country only had 1,300 runners so we didn’t know what it was like to organise an event like that.

“But it went well. Everyone was happy, the atmosphere was amazing and I was then asked the question at the end of the run ‘Are you going to do it again?’ And my answer was simple: I’ve got no choice in the matter’.’’

He added: “We managed to map the course out, driving a car on the tripometer to measure it, but I didn’t get involved in that.

“Of course it had to be measured out, but the first year wasn’t a half marathon, it was more than that. Then we decided on a half marathon, a proper distance.

“Some people said we should make it a marathon, but we resisted that for two reasons: people are more likely to run a half marathon and you cannot get any further than South Shields when you get to the coast!’’

Starting a race of any size takes planning, organisation and a determination. There’s no hurdles to clear along the route, but there was plenty for Foster and his team of four to get over.

“Initially the police said no, then they allowed us to do what we wanted,’’ recalled Foster. “Closing the Tyne Bridge was a big thing, the only time it had been closed before we got the Great North Run started was the opening with King George VI, so we are in good company.

“It’s an iconic image, the Tyne Bridge. The key shot is the runners going over it with the Red Arrows flying across – it never ceases to amaze me.

“We are in the queue for the Red Arrows again, they love to do it and we hope they come again this year.’’

He smiled: “Kevin Keegan did it, in the second year, he was a professional footballer. Professional sportsmen weren’t allowed to compete in amateur athletics events, so we got into trouble.

“They told us in the second year we weren’t going to get permission to go ahead with the event. So I told them, right – you come and tell everyone they can’t do it because I’m not!’’

The public ballot is open now and it’s already attracted more runners hoping to nab one of the 57,000 places than previous years.

South Shields in September seems a long way around now, but it’s not for Foster and co.

He added: “The finish line in South Shields is iconic and now it’s exciting that people are training now for getting across the finish line. We have to make that exiting, with music, sound and a new dimension so people love it and come back again.

“We never expected it to get this big because nothing had ever been this big. We started with 11,000 entries – almost ten times more than any other event in the county. We just couldn’t envisage that then and we can’t now.

“People still want to come along and do it - more this year than ever before. In sport you can stand outside looking in, but this is about getting in. Go to St James’ Park, Stadium of Light, Durham Cricket Club and look on. This isn’t like that, it’s about coming in, taking part and being part of it. There’s a piece of this for everyone.’’

Mo Farah has won the last six Great North Runs. There’s every chance he will go for seven in September. Having the world’s finest runners pacing along John Reid Road, past the homes of South Tyneside residents is part of the attraction. The crowds respond to the elite as much as they do the fun runners, those in fancy dress, the dinosaurs, monkeys and mascots.

Mike McLeod, Tynesider born and bred and of international standard won the first in 1981. The benchmark had been set.

“From day one we have always attracted the elite athletes,’’ added Foster. “Now they all know about the Great North Run and these big athletes want to be in it. Mo Farah wants to win it again, we want him to run again, we want someone to run against him again. That makes it a big event when they want to take part.

“Go with the women’s list of winners and anyone who is anyone in the elite group over the years has won it.’’

From those quiet and simple beginnings in Gateshead a little over 40 years ago, the Great North Run has become something known and respected across the globe.

This year it encompasses a weekend, with runs on the Friday evening and Saturday before the main event. It’s becoming a festival of running as much as a race.

Foster takes a back seat these days, his role in charge of the Great Run Company is at an end. He knows it’s in safe hands, but he can’t help but ponder what comes next and beyond the 40th anniversary.

“It’s not just where the event is now. People who organise the event, they need to sit down now and ask what the event looks like in 10 years time, in 20 years time. One of the biggest challenges is to stay top of the pile.

“Look in sport and Manchester United were top of the pile, but not now. Newcastle United were nearly top of the pile. Individual sportsmen were top of the pile, but not now. Unless you plan to be top of the pile in the future you won’t be.

“In any walk of life if you don’t get better, you get worse because people catch you up. Sit there and take it for granted and you don’t stay at the top.

“That’s true in sport, life, business and now it’s up to the team about what they are going to do next.’’

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here