Major Tim Brown, the only Briton to command tanks in both Gulf Wars, formed a special bond with the mighty war machine during his military life. He tells Steve Pratt about his fears for the future of the tank in warfare as a new book about his regiment is published.

THE occasional distant rumble that disturbs the peace and quiet of the Yorkshire countryside is a reminder of Major Tim Brown’s past life. “I live between Leyburn and Bedale and you can hear the roar of the Challenger up in the training area from time to time. You never forget the roar of tanks and when I hear it...”

His voice trails off as his mind goes back to the battlefields of two Gulf wars, a million miles away from the estate agent’s office in Bedale, where he now works as head of property sales.

But his attachment to the mighty war machine and the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards is obvious.

He now lives – with wife Sonia and son Tom, 15 – in the Dales, where he enjoys country pursuits like walking and shooting and indoor pursuits like trying all the beers in Yorkshire.

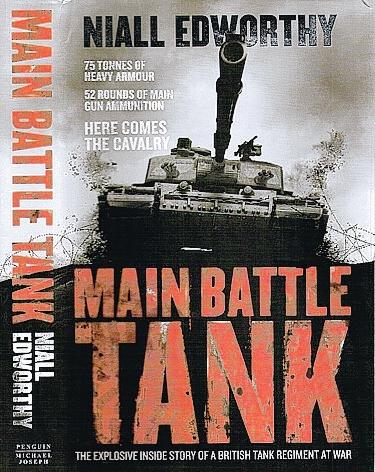

But four years after leaving the Army – with the distinction of being the only Brit to command tanks in both Gulf wars – he has recalled his battlefield experiences in a book, Main Tank Battle, which aims to make us see tanks in a whole new light.

Author Niall Edworthy sees it as recent history told in the style of a thriller, rather than a dry chronicle of events. Brown, 46, was one of three squadron leaders interviewed for the book – and he approves wholeheartedly of the approach.

“The nice thing is Niall said he wanted it to be a readable book, a story – faction, as he called it – rather than just a textbook,”

says Brown. “The final result is a very accurate account of what happened, but written with a really good touch that puts you in the turret of a tank. For someone who has never served in a tank, he’s really captured the spirit of the tank crew.”

The book is also a chance to put the case for this war machine, whose place in the Army of the future is the subject of some debate.

“Technology has produced tanks now that are absolutely superb in terms of armour, mobility, speed, protection and firepower. But it takes about 20 years to design the next generation of tank and throughout my life that’s been happening. One tank comes out and they’re starting research on the next one.

“And I believe there is no replacement for Challenger II. There’s no future tank because the attack helicopter has to a large extent taken over in terms of firepower. But it can’t cover the ground and can never have that morale-boosting effect that tanks have on the battlefield, which is cataclysmic really.

“The cavalry has been such an influential part of the battlefield going back to Alexander the Great, offering very fast, shock action and huge morale boost. And yet, in less than 100 years, we could have seen the first and the last tank.

“Now the majority of tanks are being mothballed.

The trouble is once that happens you lose the expertise. But it’s an expensive thing to have up your sleeve because you keep a tank 365 days of the year – blokes have to work on it, change parts and all the rest – all for the day when they might go into action.

“For 30 years during the Cold War, we had all those tanks and they were never called into action.

Over the past 20 years, tanks have been deployed three times in operations – in two Gulf wars and Kosovo – and yet we’re looking at them being pulled out of service. So I think it’s a bit short-sighted, but that’s because I’ve got a soft spot for them.”

BROWN followed his father, Kenneth Brown, into the regiment after studying estate management and deciding he’d like to go into the Army before starting a career as a chartered surveyor.

“He’d been in tanks, so I joined in the late Eighties with a view to doing a few years. The Cold War was still on and it was a bit of a shock when the first Gulf war came along and suddenly we had to go off to war, which meant postponing my wedding.”

He stayed in the Army for 19 years, commanding a tank squadron in both Gulf wars.

“It’s a lot more complex commanding tanks. It’s a physical and mental challenge, it’s an awesome beast. My choice of regiment was based on family history, but I think very few people who join the cavalry join to command tanks.

You grow into tanks. It’s funny how you form a fondness, a bond with them and your fellow soldiers.

“It’s quite a unique thing, and the bond within a tank crew is very close, much closer than the infantry have or the artillery. Relationships within a cavalry regiment are much stronger and much closer because you work so closely.

“For instance, in my tank of four, there’s me sitting at the top as a major and my driver was a trooper, so a massive difference, but you become very close. You sleep and you work so closely together.”

He led the raid by British tanks into Basra in Iraq in 2003 that took out a 20ft high statue of Saddam Hussein, a television and radio mast and a Fedayeen headquarters. Using tanks in towns led to one bizarre incident. His tank had lined up the building to be targeted and was ready to fire when his gunner spotted a man in a jacket and shirt carrying a leather briefcase about to cross the road.

As he approached the Challengers, his head a few feet below Zero Bravo’s muzzle, he looked up at the tank, nodded and smiled as if to say thanks for giving him the right of way. Brown held fire until he was safely across the street.

His way of dealing with the dual feeling of excitement and danger was to compartmentalise it. “There are times when you allow yourself to think about the dangers and the consequences.

Other times – the majority of times – you just put it aside and get on with the job in hand,” he says.

The scariest moment was an artillery attack which began while the squadron was asleep in its hide. “Yes, there are scary moments when you’re in action and you can see rounds flying around. The artillery was horrendously scary; then, two hours later, we had to lead the raid on Basra,” he says.

■ Main Tank Battle is published in Penguin Hardback, £20

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here