NO great understanding of the manifold mysteries of the Church of England may be needed to appreciate that few go from being curate – not even of St Nic’s in Durham Market Place – to bishop in one go. Alfred Tucker did.

He became Bishop of Uganda in 1890, shortly after a predecessor had been murdered by the natives, finding just 200 Christians there. When he left 20 years later, there were 83,000. Among them, doubtless, were ancestors of the present Archbishop of York, Dr John Tucker Sentamu.

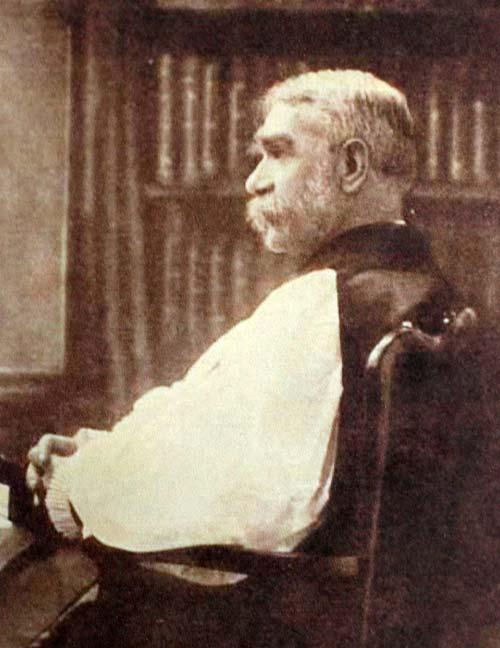

Known as the Ugandan Express – though possibly not to his face – Tucker travelled 22,000 miles, on foot, and wrote 4,200 letters. He is buried outside Durham Cathedral, the grave marked by that familiar Celtic cross outside the north door.

How many, passer-by or pilgrim, know what it represents, or whose mortal remains it marks? “He is nothing like as well remembered as he should be,” says the Reverend David Webster. “Anglicans do not declare people saints, but to my mind he was a very great man.

“We also find it hard to attribute miracles, but to have a spiritual child of Alfred Tucker being Archbishop of York is for me nothing short of a miracle worthy of a very English saint.”

Randall Davidson, a long-serving Archbishop of Canterbury, would clearly have agreed. In the foreword to a 1929 biography he wrote of Tucker’s tireless courage and resource.

“Familiar as his name became in church circles, and far beyond them, I do not think his greatness has ever been appreciated to the full.”

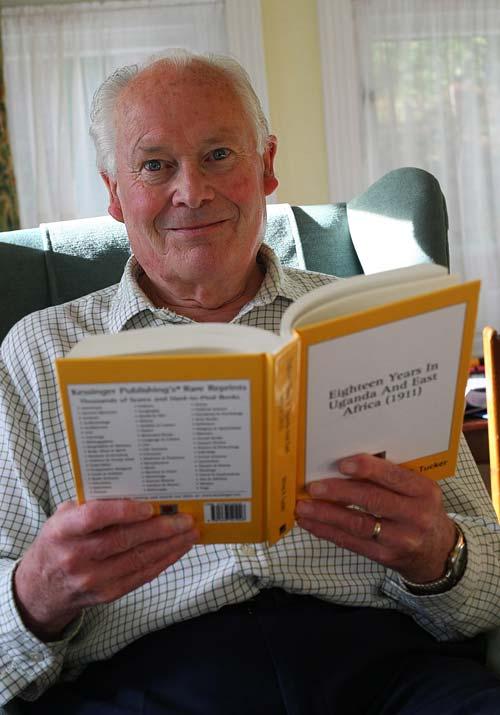

It’s thanks to David Webster, a 78- year-old retired parish priest, that Bishop Alfred Tucker is again to be remembered.

TUCKER was born in the Lake District in 1849, became a mature student at Oxford, was ordained curate in 1882 and three years later moved to Durham.

He is said to have told Henry Fox, St Nicholas’s vicar, that he didn’t expect to be there long. East Africa – wild, pagan, uncharted – was calling.

He was also an outstanding painter, had nine works hung at the Royal Academy, paid for his education by selling his pictures. Some are said to be still in the Durham County record office.

James Hannington, the first Bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa, had been captured, tortured, put on show for a week and then killed with spears. His successor died of fever on the way to replace him.

Tucker offered to go in his place, was appointed bishop by the Archbishop of Canterbury. His diocese, notes David Webster in a pamphlet, was 700 miles east to west, 500 north to south and six times the size of England.

First he had to get there. “There were no roads and no railways,” writes Mr Webster. “There was tropical forest with its animals and snakes, fever-ridden swamps with their malarial mosquitoes, desert areas with very few wells, crocodile infested rivers and a mountain pass of 5,300ft.”

Many died along the way. Bishop Tucker suffered, became for a time almost blind, but made it to Lake Victoria, and to what became Uganda.

For Alfred Robert Tucker there was no such thing as mission impossible.

In 1891, there were 70 communicants, in 1907 18,078. The number of worshippers rose from 25,300 in 1897 to 52,471 in 1907, the number of churches from 321 to 1,070.

By 1901, Tucker had helped establish hospitals with 158 beds and clinics that saw 127,000 people each year.

There were trade schools and mission schools, the number of lay evangelists rose from six to 2,036 with 32 native clergy.

He was instrumental in the abolition of slavery and also helped build a railway, returning to England – and to a public meeting in Durham town hall – to help raise the money. “Never in the modern annals of the City of Durham has such an assemblage been seen,” reported the Durham Chronicle. “The whole city was there in person or by representation.”

He raised £15,000 in a fortnight.

The railway was built.

In 1910, ill health forced Tucker’s return to England, where soon afterwards he was offered a canonry at Durham, the city which he loved.

He was to discover, however, that the Cathedral authorities were far too greatly concerned with pomp and circumstance at the expense of what Tucker thought should be their priorities.

“The Church,” he wrote – and a century later it may sound awfully familiar – “is not equal to the occasion.

Far too much of her energy is consumed in forging for itself ecclesiastical fetters.”

On another occasion, the Cathedral top brass had spent half an hour debating who should carry which communion vessel. “I asked myself,” wrote Tucker, “whether it was for that that I had come back from the mission station.”

The highlight of his last years in Durham was the visit of the young king – whose father had not only ordered the killing of Bishop Hannington but all but wiped Christianity from Uganda. Tucker had converted him.

They visited town and village, dock and colliery, knelt together at the communion rail in Durham Cathedral.

Though he had been ill, a legacy of 20 years in Africa not helped by the then-as-now North-East winters, his death on Monday, June 15, 1914 was unexpected – perhaps not least by The Northern Echo which allowed it just two down-column paragraphs on the front page.

We’d a little more the following day, seven paragraphs when his funeral service was held in Durham Cathedral four days after his passing.

The great church overflowed; the summer sun shone brightly. “To think,” said the Echo, “that he was once only a curate in Durham.”

DAVID Webster was a curate in Billingham, vicar of Lumley near Chester-le-Street and of Belmont, Durham. He retired in 1993 and now lives in Hartlepool.

His eagerness posthumously to raise Tucker’s profile led to letters to the Cathedral chapter – and to action.

The centenary of his death will be marked on October 29, 2014 – the day on which the Church remembers Bishop Hannington’s martyrdom – with a special evensong and a procession to that familiar Celtic cross.

A chalice owned by Selwyn College, Cambridge – from which Mr Webster graduated – will be loaned for the occasion. It includes Bishop Tucker’s wife’s wedding ring.

“With the service still three-and-ahalf years away, that’s as much as has been arranged,” David Sudron, the Cathedral sacrist, tells the column.

“I’m very happy about it,” says David Webster. “I very much hope that I will still be able to be there."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here