The first Butlin’s holiday camp opened 75 years ago next month. A new book warms to the Redcoats.

BILLY Butlin was born in South Africa in 1899, moved to England and then to Canada, lied about his age to become a bugler in the Canadian army and then worked his way back to England on a cattle ship.

He landed with just £5 to his name, £4 of which he paid to take over the hoopla stall on his uncle’s travelling fair. His aunt sold gingerbread on the next one. Stall set out, Butlin burgeoned.

Part of his success, it’s said, was that he’d sawn the corners off his hoopla blocks so that punters might win. That way they’d come back more often.

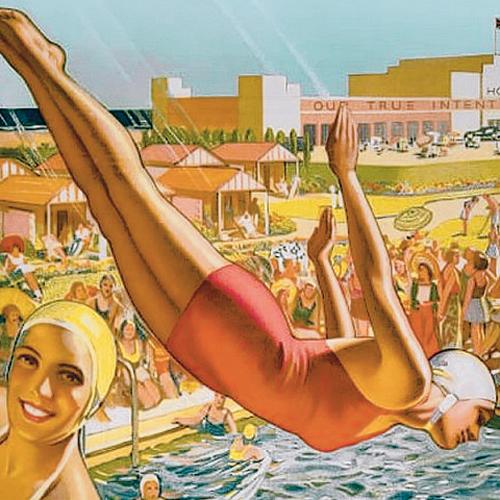

By 1927, he owned a static fair in so-bracing Skegness, had won exclusive rights to import dodgem cars and had customers going through the hoopla at Olympia. Still nursing memories of a childhood holiday where the landlady locked them out all day, he then planned his first holiday camp. With the watchword “Our true intent is all your delight”

– thought aptly to have been pinched from A Midsummer Night’s Dream – it was built on turnip fields at Ingoldmells, near Skeggy and opened by Amy Johnson, the aviator, 75 years ago on April 11. A week’s break began at 35 shillings.

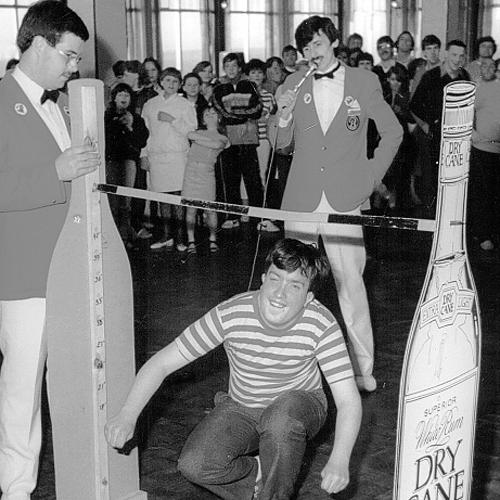

Soon Butlin’s had tens of thousands of camp followers. The biggest, at Filey near Scarborough, covered 400 acres, could accommodate 12,000 all-in holidaymakers and employed 1,000 staff. The best remembered were the Redcoats – the Reds, they called themselves – in a different age the endlessly enthusiastic epitome of the hi-de-high life.

To mark the 75th anniversary, Frank McGroarty and Rocky Mason, Reds in truth and clause, have combined on an affectionately, appropriately jolly book and are helping organise an October reunion in Scarborough.

The book’s sub-titled “A celebration of a holiday institution”, which may be a little ambiguous. They mean the Redcoats, not the captivating camp itself.

Actor/comedian Tony Peers, himself a Scarborough legend, reckons in the introduction that the Redcoats were the “real heroes” of Butlin’s – “the thousands who toiled at the coal face of entertainment, from first-sitting breakfast to late-night entertainment.”

Frank still smiles at the memory.

“The adrenaline pumped 24/7, the job satisfaction was tremendous. It was either the best job in the world or the worst job in the world, depending on what you wanted out of it, but it certainly wasn’t about being a star. It was such an accolade to put on that red jacket. You even took pride in calling the bingo.”

BACK in 1936, however, they weren’t very happy campers at all. Billy Butlin thought them bored, discussed it with the site engineer – a cheery chap called Norman Baker – told him to get a red jacket and inject some life into the proceedings.

It worked at once, the Redcoats a force to be reckoned with. Those who subsequently became stars ranged from Helen Shapiro to Clinton Ford, from Terry Scott to Freddie Davis.

Comedian Charlie Drake also began at Filey, teaching boxing and jujitsu, afforded the dubious distinction of being personally sacked by Butlin after being caught fiddling the bingo.

From the moment of arrival at the railway station to the time of departure seven days later – “instant friends, elevated almost to celebrity status by the end of the week”, says Frank – the Reds became the smiling face of Butlin’s, formally instructed to mix and to mingle. “Don’t seek out the young and attractive,” said one standing order, “they’ll quickly find friends of their own”.

Among the key jobs, mixing and mingling, were the endless competitions, from knobbly knees to donkey derby. Butlin, it’s said, had introduced glamorous granny after finding himself on a plane next to the actress Marlene Dietrich, the model of glamorous grandeur. “You can’t be a grandmother,” he told her. The rest is Butlin folklore.

When Frank McGroarty started at the Ayr camp in 1982, the take-home pay was £38 for a six-day week that usually meant working 16 hours a day. The chalet-alley accommodation could best be described as basic – two iron beds, a chest of drawers and a curtain on a frame which served as a wardrobe. It hardly mattered.

“The long hours and low pay were just a side issue,” he says. “It was just an iconic thing to be a Redcoat.”

The Filey camp lasted until 1983, was briefly reopened in 1986 as Amtree Park by Harrogate millionaire Trevor Guy – whatever happened to that young man? – but has never been redeveloped.

FOR Frank, as for millions more, Butlin’s holidays had been part of childhood. “There was such a fantastic atmosphere whichever camp you want to. I never dreamed that I’d get a job there.”

He’d worked in a bakery, was an accomplished ballroom dancer, told the job interviewer he’d had hospital radio experience. “I didn’t tell them it was reading the racing results.”

Best of all, he was to meet his wife.

Wendy Winkworth was a Middlesbrough lass, studied at technical college in Durham and hoped to be a laboratory technician. The experiment unsuccessful, she was told at the Job Centre that Butlin’s were interviewing down the street and – “any job better than none at all” – worked in the kitchens in Ayr.

The following year she became a Redcoat, loved it. Her parents now live in Ferryhill Station. “It was hard work, but wonderful. I feel quite sorry for the Redcoats today because they can’t do all sorts of things that we did because of health and safety and working hours directives.

“It wasn’t hard to keep cheerful.

The campers were there to have fun; we did it together.”

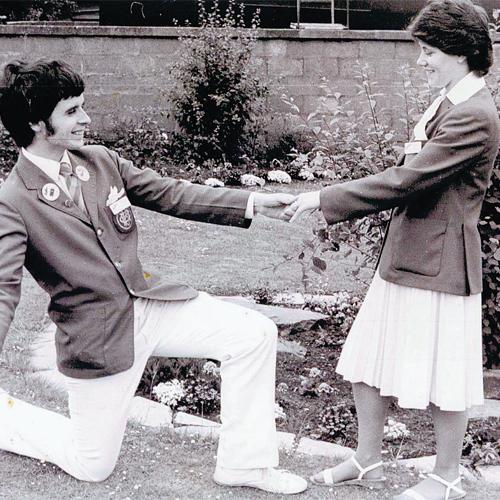

She and Frank were on reception duty at Ayr station, joined by a fullfig piper called Tony Middleton – he was from Bishop Auckland – when Frank used the dinner hour to go down on one knee to propose. “It brought the whole station to a halt,”

she says.

Frank’s now unemployed, lives in Scotland, describes his book as work experience with a difference. “I mean no offence to them, but being a Redcoat probably isn’t the same these days.”

Rocky Mason, a former Butlin’s entertainment manager, is 80 and lives in Bristol. The co-authors have never even met, though there’ll be plenty of time for reminiscence at the Redcoat reunion at the Grand Hotel – another former Butlin’s emporium – from October 7 to 9.

“The response has been fantastic,”

says Frank. Camping it up once again.

• Evocatively and extensively illustrated, Here Come the Redcoats is published by Authorhouse UK, price £11.99, and with infrequent exceptions – “One of my saddest days was when Gertrude the elephant drowned in the south pool” – is as relentlessly cheerful as its heroes. Full details of the book and of the reunion at irnwurksmedia.com/redcoats

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel