As former pitman and quiet hero of the Labour party John Toft logs on to his tenth decade, he explains why Tony Blair was such a huge disappointment.

NINETY not out, one of the great pillars – the pit props – of the North- East Labour party and trades union movement marked his birthday with a surprise gathering at Durham County Cricket Club.

John Toft received written congratulations from both Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband – “one of the quiet heroes of our party and country,”

said the new leader, though the quiet hero is vocal when talking of Tony Blair.

“My last public speech was on the same platform as Blair, but frankly I don’t boast about it,” he says.

“I disagree with him about almost everything he did – the tragedy of Iraq, the madness of Afghanistan – all except the minimum wage. He had the opportunity to change the world and he didn’t – well he did, but he did it by embracing Margaret Thatcher.

“It’s such a tragedy, but people now need to realise that we’re just a small island off Europe. We’ve no power any more; the decisions are taken elsewhere.”

To take him into his tenth decade, he’s got himself a first laptop computer.

“I’m frightened to death of it,”

he admits. “People tell me it’s going to be a force for good, but I fear it’s a force for evil. I’m having to learn very slowly.”

He was born and remains in Murton, in the former east Durham coalfield, one of a family of nine brought up in a one-bedroom house in the area known as Cornwall because of a past influx of west country tin miners.

“The boys slept head to toe in the kitchen and the girls the same,” he recalls.

He was third in the class but failed the 11+ – “being third meant I had to sit at the back, I couldn’t see the board” – was 14 when he followed his father and grandfather down the pit, can’t remember how much he earned but knows that a bank hand got 28 shillings and that, as a pony putter, he was on a great deal less than that.

“There was poverty, but the compensation was that it was shared poverty. We had a real community. If someone baked, everyone was round there. If Paddy Killeen who lived next door killed a pig, everyone would get a bit. Those pigs had 24 legs.”

He joined Murton parish council in 1947, became colliery lodge chairman ten years later and in 1964 was elected to Durham County Council, which he chaired from 1973-75. He has a 70-year meritorious service award from the Labour party.

He’s been involved in everything in that coal-hewn community from operatic society to cricket club, studied in Paris, was a governor of many schools, served on the Durham University Council from 1977-94 and is a Fellow of St Cuthbert’s College, where also he was a governor.

“I was obviously influenced by the rotten conditions down the pit,” he says. “People didn’t deserve to have to work like that and today they don’t realise how bad it was. It marked my life.”

He was lodge chairman during the strikes of 1972 and 1974 – “I could write a book about that alone” – retired in 1980, swears there’s still seven-foot seams of coal down there, views the old village with mixed feelings.

“I’m not displeased with the way it looks. There’s all sorts of new houses going up and that Dalton Park shopping centre is remarkable. People flock from all over.

“I was all for it because it meant employment but at one time I could walk down Woods Terrace, the main shopping street, and know everybody.

Now I don’t know a soul.

“The pit held the village together, created employment in some cases for people who were otherwise unemployable.

“I suppose there’s also a drug scene and all that in Murton. It didn’t happen in the old days because from the age of 14 you were down the pit, in it together. There was a work ethic and Thatcher abolished it.”

The work ethic was also part of the Methodist tradition in which he was brought up, and which also ensured that he drank little – “I was never very good at it” – and smoked less.

Longevity, he supposes, must be in the genes.

Though never much of a cricketer – “eyesight; I did once score 35 not out” – his 90th birthday venue was appropriate. He’d been involved when Durham initially explored becoming a first-class county, became a debenture holder – guaranteeing a seat for ten years – was also a member of Yorkshire and of the Surrey Taverners.

Cricket and community, colliery and college were all represented at the celebration, organised by his friend John Creaby. John Creaby reckons it went very well – “John Toft is a true North-East character”

– the quiet hero still glad to have been remembered.

“I just hope,” he says, “that I’ve been able to make a little bit of a difference to things.”

FROM one remarkable nonagenarian to another and, specifically, to his wife. “A child bride,” we are assured.

Former town planner Franklin Medhurst, awarded the DFC in the Second World War, was in the news last month following publication of his book “A Quiet Catastrophe: the Teesside Job”. Particularly it concerned the blight that is Stockton town centre, already it’s been twice reprinted.

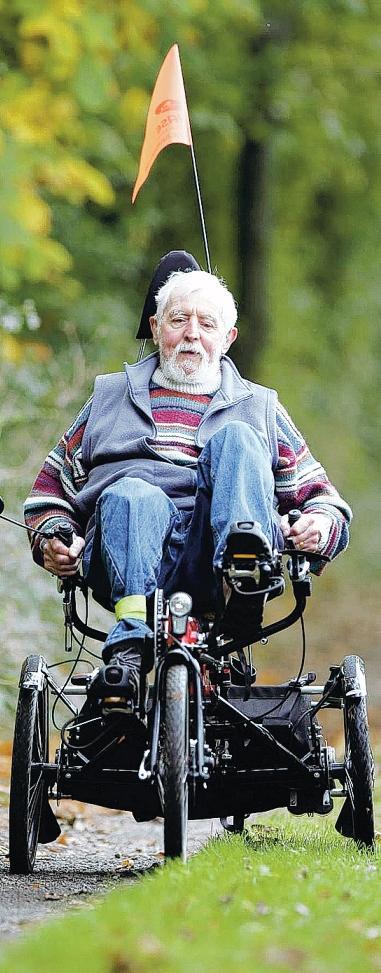

Three years ago, his right leg was amputated below the knee. Still he gets about, up to ten miles a day, on a specially adapted tricycle. “I was told I could have an electric one, but I thought it would be cheating,” he said.

What’s more, we’re told, he still irons his own shirts, an’ all.

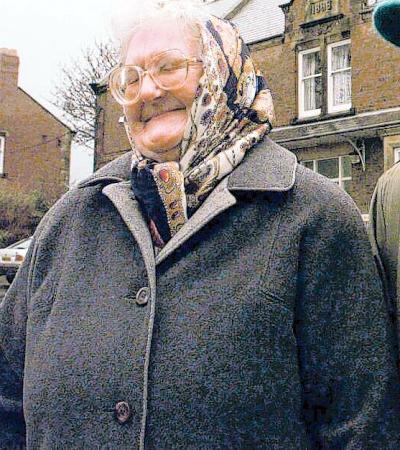

It’s to Jenny Medhurst we turn, however, and to the 25th Fairtrade Christmas shop in Middlesbrough.

Every year she scouts around for suitable town centre premises, marshals an army of volunteers to run it, oversees things every day.

This year the shop’s next to Debenham’s, opposite the House of Fraser.

Except for Sundays, it’s open daily until December 21 from 10am-5pm.

Zurbaran sale? Not on your Nellie!

THOSE who plot by stealth the sale of the Zurbarans, those precious paintings in Auckland Castle, have a new and formidable opponent. Nellie Bowser has written to the Queen.

“Why not, she’s head of our church?” asks 87-year-old Nellie.

“I’m sure she’d like to speak on our behalf.”

Bombed out of London during the Blitz, still with an accent as broad as the Embankment, Nellie has long been in West Auckland. For 40 years she helped her friend Mary Hodgson organise the Tindale Crescent Hospital garden party among much other community work; and in the 2001 New Year honours list received the MBE.

It’s possible, she supposes, that Her Majesty won’t remember but impossible that she won’t be sympathetic.

“It’s all wrong what the Church Commissioners are doing and the way they’re doing it. I’ve written her a very nice letter; I’m sure she’ll help.”

LAST week’s piece on the 40th, trumpet-blowing anniversary of the Tees Valley Jazzmen also noted their efforts to raise money for Cystic Fibrosis Research.

Among others similarly committed is Kate Upshall Davis, back from completing the New York Marathon just 18 months after taking up running.

“I used to hate it at school. I’d do anything to avoid it,” admits Kate, 34.

Like the Jazzmen, she was inspired by the case of the two grandchildren of Norma Salisbury, partner of band co-founder Gavin Belton, who were both born with the disease.

Kate joined the Low Fell Running Club, entered last year’s great North Run in aid of the Crisis charity for which she works in Gateshead, chose the New York Marathon because of its reputation for a great atmosphere and managed it in five hours 33 minutes. “There were a surprising number of hills,” she says.

Kate’s already raised £2,600, hopes to top £3,000. Donations can be made online at justgiving.com/kateis goingtonewyork This Saturday at the Glaxo Social Club in Barnard Castle, the band is joined by the Fenner Sisters from Sedgefield in another concert for cystic fibrosis research. Tickets are £8, including pie and peas supper. Details on 01833-638926 or 07887-520412.

WE’D also anticipated last week the forthcoming fortieth anniversary, on New Year’s Eve, of what began as BBC Radio Teesside. George Lambelle, who presented the opening programme, recalls an unscripted distraction.

George was in the production office when a lovely young lady came in, asked if he were married and – assured that he was – proceeded to remove her clothes at the other end of the room.

She was a guest, George was aghast. “It seems she was a model of some kind,” he says, perhaps euphemistically.

Having assumed a flashy scarlet rig, the lady in red then asked him to zip her up. “I was on air in ten minutes, with sound checks to be included in that time. The opening went ahead with my voice four tones higher than usual. It was only later that someone found her frilly knickers.”

JOHN Heslop, now in Durham, recalls that BBC Radio Teesside began shortly after he graduated from Teesside Poly in 1969, the occasion marked by a “Song for Teesside”

competition. Shortlisted numbers were performed on air by the resident band at the Fiesta night club in Stockton.

At any rate, a friend of John’s – a Dave Brubeck jazz fan – submitted something called The Girl from Teesside (who may or not have been closely related to the Girl from Ipanema.) The song, alas, was rejected because it was too complicated.

Teesside girls are doubtless the same today.

BACK in July we reported outline proposals to redraw the Methodist church map in the Darlington district. If accepted, they’d have meant the closure of village chapels at Gainford, Piercebridge, Barton and North Cowton and the retention of just three Darlington churches for regular Sunday worship.

Following consultation, there’s been a rethink. It’s believed that village chapel closures are on hold though there’ll be further discussions at a meeting tonight.

A report warns, however, that little has fundamentally changed in regard to falling numbers, overstretched resources and financial concerns. “If we carry on as we are, then the future of Methodism in Darlington is bleak.”

THE week before the Methodist ministrations, we’d told the story of the Reccies – the Reconnaissance Corps – based at Reeth, in Swaledale, for part of the Second World War.

For much of the time they were commanded by Major John Parry who, having ferried his beagle pack across London in a black cab, brought them north on the train.

The Reccies’ crew proved colourful cohabitants.

The column of July 22 told of plans to erect a plaque in their memory outside the Burgoyne Hotel, which had been their wartime base.

Last Sunday, Remembrance Day, it was duly dedicated. “A fitting occasion,”

reports Tom Peacock.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article