We raise a glass to passing publicans, Darlington’s Albert Hill and the painting and sculpting wizard of Oz.

IT’S a small world, even from here to Australia. A serendipitous one, too, as Harry McNeilly’s unannounced arrival in this office again underlines.

A few days earlier we’d been reminiscing about Edie Darby’s four bob feasts at the Forge Tavern on Albert Hill. Harry’s bearing a book, a very strictly limited edition. Since someone got first to The Folk That Lived on the Hill, it’s called The Hill and Other Memories.

The book’s by Billy Rees, William E Rees when on parade, and thereby hangs yet another tale.

Back-to-back, Harry and Billy grew up on Albert Hill, one in Allan Street, the other in Lucknow Street.

“It was a real community,” recalls Harry. “Fifty per cent Catholic and fifty per cent Protestant and never the slightest bit of bother.

“Mind, it could be rough and ready.

If you saw a dog with two ears, it was probably a tourist.”

Born in 1933, his grandfather steward of the old Nestfield Unionist club, Billy went to Gurney Pease school, was a choir boy at St James the Great – ah, dear old St James the Great – worked for a while at Darlington Forge (“desperate days”) after service in the RAF.

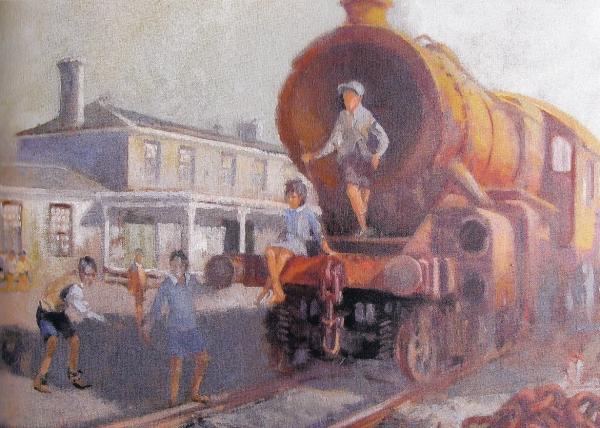

As an RAF caterer he’d cooked for the Queen and Prince Philip, won numerous awards for the intricacy of his icing sculptures, was awarded the BEM. He’d moulded it, as it were, by making streamlined steam engines from the clay found beneath Albert Hill’s paving stones.

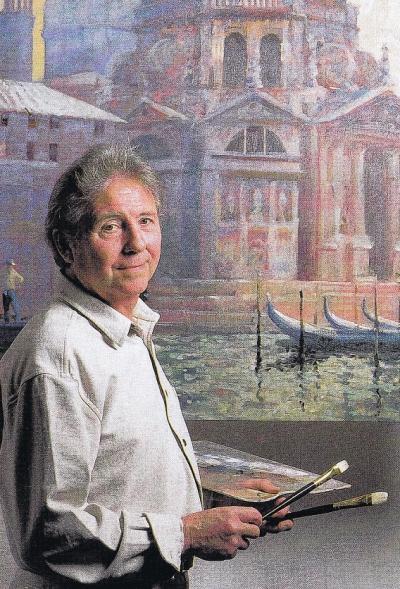

He was also a nature lover, a sculptor and a painter.

“I couldn’t spell so I drew pictures instead,” he insists, down a 12,000- mile line as clear as if we were enjoying a beer in the back bar of Albert Hill club.

As an artist he was in much demand locally, as a sculptor the man responsible for the affectionately remembered collecting boxes in the image of Brother George, he of the order of St John of God at Scorton and the most marvellous, most mischievous, of monks.

They were meant to be a surprise.

Somehow, however, Billy had to get the measure of his subject. “They introduced me to him as if I were a journalist,” he recalls. “George was very shrewd, knew something was going on. He got quite huffy in the end.”

Remember the Morris Minor mendicant who endeared himself to many? He died, aged 92, in February 2003, two years after the Darlington & Stockton Times leader column had described him as “the late” Brother George. After seven days he was resurrected.

“Everybody thinks the old beggar dropped off years ago,”

George protested. The collecting boxes are now collectors’ items themselves.

In 1984, Billy and his wife Sheila emigrated to Australia, thought they’d give it a year, remain. He’s still working, prospers, has made life-size bronze horse sculptures for the Sultan of Brunei, lives in Double Bay, an affluent waterfront suburb of Sydney.

“People here call it Double Pay,”

says Billy. It’s an awfully long way from Albert Hill, anyway.

THE book’s beautifully produced – “you can do anything in the computer age,” says Billy – a nostalgic mix of amateur verse and highly professional art recalling a perfect childhood, and wartime, on the Hill.

“I really just did it for our kids as some sort of reminder,” says Billy.

“Those days have gone, Albert Hill’s totally changed. I was really quite annoyed that there was nothing to remember them by.”

It wasn’t much different, of course, from any of the North-East mining communities or, come to that, from Shildon.

“Oh Shildon Works?” says Billy.

“I’m sure not.”

There are memories of club trips and of whist schools, of smoke and of slag heaps, of digging for victory, of the Five Arch bridge, the Black Park, Mrs Metcalfe’s pork pies and of Katie Duff who delivered the papers.

Old Katie Duff with her very small stature

Would pee in the grate while still looking right at yer.

He recalls the matriarchs, the muck, the skirmishes with the Over the Hill gang, women like his mother – the future Aycliffe Angels – arriving exhausted back at North Road railway station after a long shift at the munitions factory.

Working at Heighington was not always fun

But the work was essential, like carrying a gun.

“Everyone knew everyone else. It was a real community, a perfect childhood,” says Billy. “It’s quite sad, especially all this way away, to think of all the mates you grew up with and that quite a lot of them are gone.

“That’s what prompted me really.

It’s what made me write something down.”

Recalling 30-a-side football matches, a verse on the last page may sum it all up.

That was the bonding of old Albert Hill

With a tear in my eye, I run with them still.

Now time has passed and some are far flung

I sit down and wonder about the unsung.

Some that I know have done well indeed

The Hill that we knew nurtured many a good seed

We might have talked all day but from here to Australia you don’t get a lot of time for twopence. Billy doesn’t suppose they’ll be back. We’re getting a bit long in the tooth now, the family visits us, but I can see it like it was yesterday.

“It was a great place, Albert Hill.”

Albert Hill rides again

IT IS impossible to write of Albert Hill, and of Darlington, without catching up with what might be termed the “other” Albert Hill. His readers know him as Elliot Conway.

Albert writes westerns, rides the range. The first was published on his 65th birthday, the 44th on his 87th, all by Robert Hale. He’ll be 88 this month, celebrated his diamond wedding earlier this year, still runs creative writing courses at Longfield school, chairs Darlington Writers’ Circle, worries about where the 45th is coming from. “I had writer’s block for two years, probably something to do with a prostate operation, though I’m all right now,” he reports.

The latest is called The Death Shadow Riders – “a good title at least,” says Albert, modestly – the next may be some time. He’s started, as always in longhand, but nowhere near finished.

“I’m slowing up. The last few have been a bit of a bind, but I’m going to have to get down to it.”

He was a Sunderland lad, saw wartime service in Burma, worked as a bill poster and wrote bits and pieces for the papers. The name’s coincidental, though he lives nearby.

“There were so many fantastic characters on Albert Hill.

Unfortunately they all appear to have gone,” he reflects.

Mind, the old place had seen better days. Albert recalls a Northern Echo contents bill: “Albert Hill: a blot on the town.”

He was upset, he says, for weeks.

EDITH Darby, a pub landlady from an altogether different age, has died 12 years after her incomparable husband.

She was 85, and smashing.

Theirs was a time when licensees might stay for 20 years, and not 20 minutes, when regulars would identify their local not by the name on the sign but by that above the door. It wasn’t a revolving door, back then.

Sadly coincidental, the death notice below Edith’s in last Thursday’s paper was for Irene Forster, former landlady of the Red Lion in Cotherstone. In that part of Teesdale, the Red Lion was simply Rene’s.

Further coincidence, at church in Lynesack, west Durham, last Sunday we fell to recalling the long-closed village pub in nearby Copley. Few may remember it as the Three Horse Shoes; universally it was Harry Boy’s.

“People like Tom and Edith were like host and hostess. It wasn’t just a business, it was a calling,”

says Ron Darby, their nephew.

“Both of them liked a drink elsewhere but would never have one in their own pub, even if they’d been locked in there for a month. It wasn’t professional.”

Ron’s been manager of the Blue Bell at Acklam, Middlesbrough, for 19 years. We looked across to see him, a large bar, well-filled and probably not a dozen he didn’t know by name.

“The trouble with so many pubs today,” said Ron, “is that no one even knows who the landlord is.”

TOM and Edith came from the Trimdons, where he’d been a colliery blacksmith, became stewards of Chilton club, moved to Darlington where they had the Alexandria – opposite the non-stop Rolling Mills – and, best remembered of all, the Forge Tavern on Albert Hill.

Albert Hill was then a hammerand- tongs industrial area, cheek by heavy jowl with long rows of terraced housing. It was hungry and thirsty work and, early 1970s, Edith would knock out roast lunches for 17p.

“I know myself that food prices are scandalous,” she explained.

“Last week I paid five shillings for a chicken sandwich in Newcastle.”

Edith also did outside catering.

“I especially remember one do in Shildon,” says Ron. “Shildon had never seen anything like it.”

They moved to the Royal Oak in Consett and then to the Newcastle Arms, near St James’ Park, about which more shortly.

Both were dedicated Licensed Victuallers’ officials, both enthusiastic charity workers. “They’d be as comfortable with Sir Paul Nicholson as they would with the lads in the bar,” Ron recalls. “They were also very good friends with Bobby Thompson.”

Edith died in office, lady president of Newcastle LVA. She had become a widely travelled toastmistress, had a rather less formal party piece involving a song about a Little Pink Nightie. Someone may know the words.

Our obituary to Tommy remained framed on her wall in Newcastle.

He was a gentleman, we’d said, and Edith – bless her – was every inch the lady. Her funeral was on Monday.

IT was during Tom and Edith’s time at the Newcastle Arms that I’d first arranged to interview Paul Gascoigne, in the public bar after training. It was only a cockstride from his workplace, after all.

It was February 1986. He was 18, stuck to bitter lemon, declined a second cheese and onion toastie. It was rumoured, mind, that he might seriously be addicted to midget gems. “I get jealous of Beardsley,” he said. “He eats loads of sweets and never puts on a pound.”

His talent was already recognised.

“The newspaper talk’s exciting but I won’t get carried away.

If you do that, you lose your friends,” he said.

“We’ve never been well off in our house and having a few bob’s not going to change me.” Poor Gazza.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article