An injured soldier, the American Civil War and the chance of a new life in Middlesbrough for a member of the black slave family that saved him.

HARRY DIXON JESSOP set sail for America at the age of 15, was 18 when conscripted into the Confederate cavalry in the American Civil War, was saved from almost certain death by a black slave family called Harridine, promised on his recovery to help them in any way he could and returned to England with a Southern Cross of Honor but with precious little else in the world.

“He’d been to hell and back,” says Ros Robinson, his great granddaughter, and if that’s an awful lot of information for an opening paragraph there’s an awful lot of story to tell.

The Harridines eventually asked for Jessop’s help in return, which is why the entry “Maria Harridine, visitor”

appears in the 1901 census for Middlesbrough and why Hilda Jessop, his 105-year-old granddaughter, is happy to confirm the story.

Hilda lives in a nursing home in Redmarshall, near Stockton, physically frail but mentally Brassobright.

“My aunt Hilda’s very clear on it,”

says Ros. “When Maria came on a boat to England, Harry went to Liverpool to meet her and brought her to live at the family home in Middlesbrough.

“Hilda still remembers that they had to call this little black woman Miss Harridine, and to show the greatest politeness.

“They had seven children so I suppose she was a bit like an au pair, only with more permanence and greater respect. It was the very least they could do. If they hadn’t saved his life, at least 78 people including me wouldn’t be alive today.”

Jessop died in 1909, his Southern Cross buried with him in Linthorpe cemetery and his wife, Ann Ellen, alongside. Maria Harridine has rather vanished off the radar as Ros, jumping a generation, puts it.

Now, following a chance internet encounter, she and amateur genealogist Chris Carter have written a book exploring the remarkable life and times of the man they called HDJ.

ASHORT interlude. Ros Robinson was born in Dormanstown, Redcar, in the middle of an air raid – “my mother was wearing a tin hat and a gas mask at the time” – and has herself had a pretty eventful innings.

Edmund Jones, her father, had the Warrenby Hotel and the Carpenters Arms at Felixkirk, near Thirsk, lived in Brompton, near Northallerton, and until shortly before his death was a regular correspondent to Hear All Sides and these columns.

Usually we called him erudite. Edmund wrote on everything from the Irish author James Joyce to the prices at Betty’s restaurant – £3.95 in 1991 for a cup of coffee and two scones.

Ros, who lives in Darlington, has been a teacher on Tresco, in the Scilly Isles, helped her husband run a restaurant in Penrith, for four years ran the dining room at Middlesbrough FC, became friends with Gazza and was left not just holding the baby – young Rogan, at any rate – but the baby’s rabbit as well.

“Lovely man, daft as a brush,” she says. But we digress.

HARRY DIXON JESSOP was born near Hull in 1844, worked on his grandparents’ farm and, both unhappy with farm life and inspired by William Wilberforce’s anti-slavery campaign, left to work on Mississippi river boats in the Deep South.

“Wilberforce was his hero, someone else from Hull,” says Ros. “He was only 15 but he seemed to have this dream of doing his bit to abolish slavery in America.”

HDJ, she supposes, joined the cavalry – the Alabama Partisan Rangers – because he’d worked with horses on the farm.

“He fought right through to the bitter end, but was badly wounded.

When it ended they just told him that they’d lost and to go home. It didn’t matter that his home was in Hull.”

Jessop, it’s said, was crawling through a forest when he saw a light in a hut and collapsed on the Harrdines’ doorstep. Though they themselves had nothing, they nonetheless nursed him to recovery.

Jessop, who spent another two years wandering around America, gave them a letter and contact details, promising the family help if ever they needed it. Maria, born in 1863, was but a baby.

HDJ returned to Hull, worked as a stevedore, ran a grocer’s and beer shop and finally moved to Middlesbrough, where he helped form his own stevedore company, Jessop and Young, with an office in Bridge Street.

His chronicle records helping Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to load before returning to America.

Quite when Maria Harridine arrived is unclear. What’s not in doubt is the recollection of Hilda Jessop, whose own father – story upon story – is said to have designed the upper structure of the Transporter Bridge and to have allowed her to be the first, fearless, little girl to cross it along the top.

“HDJ’s experiences in the Civil War were so awful that he didn’t talk to anyone about them except grandma, and it was she who told Hilda,”

says Ros. “Hilda knows the story absolutely.

I’ve no doubt that it’s 100 per cent true.

“I really only got to know the full account when I started visiting her.

I know she’s 105, but she’s really excited about the book.”

CHRIS CARTER was with a genealogy group in Linthorpe old cemetery when someone mentioned that the grave of a Confederate soldier was nearby.

Having an interest in the American Civil War, he asked on the internet if anyone knew any more about Jessop. “It was months later when Ros got in touch, I thought nothing more was going to come of it.

“I’ve been into the whole thing big time, lots of American research. His unit even provided an escort for President Jefferson Davis.”

The story of Maria Harridine has proved more difficult to substantiate, though a woman of the same name and age died in Southsea.

“Ros’ aunt is as bright as a button and vividly remembers meeting Miss Harridine on several occasions,” says Chris.

“I’m hoping that there may still be further discoveries to make. The whole thing is absolutely remarkable.”

Chris hopes to publish the book through a local history society. Ros Robinson insists that much of the credit for it is his. “He never met my great grandfather, of course, but I think that Chris has grown rather fond of him.”

No ordinary Joem

It was the ugly duckling, the workhorse, the shunter and gatherer. If not all stubby and brown – as, it may be recalled, the ugly duckling was – then engine number 69023 was usually mucky and black.

One of a class of 113 steam locomotives – built, remarkably, over 54 years by three different railway companies – 69023 could usually be found sidelined on the coal staithes, or the dock side, or pottering about as a station pilot.

A station pilot, it should be explained, had seriously clipped wings.

Now, however, 69023 is the Great Survivor – and last week it emerged immaculate from its shed in Darlington, resplendent in BR green and once again in steam.

“You’re bound to get a lump in your throat,” says Fred Ramshaw of the North East Locomotive Preservation Group. “You spend countless hours doing all the messy, filthy jobs, sometimes almost getting frostbite just by touching the metal and then you put fire in it again and you know it’s been worthwhile.

“I sometimes think I know that engine better than I know my wife, but it was a wonderful moment.”

Starting in 1899, the class J72s were mainly built in Darlington – and all 113 survived until 1958 when they began to be scrapped, mainly in Darlington, too, but also at Thomson’s yard in Stockton.

By 1964 just two remained. Two years later only 69023 survived, bought by a gentleman named Ainsworth for the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway and since they could hardly call it the Ugly Duckling, named Joem after Joseph and Emmeline, his parents.

Bought by NELPG in 1983, Joem – no ordinary Joem – worked on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway, was overhauled at ICI Wilton, returned to the NYMR and to a familiar pilot’s role at Grosmont, but spent several years standing round what railway folk call the deviation shed at Grosmont.

It should also be explained that the lads themselves aren’t deviant, though they do often get quite excitable.

Six years ago, Joem – built in 1951 – came on the back of a lorry to NELPG’s base in Hopetown Lane, Darlington, in need of a complete overhaul. Richard Pearson, assistant engineer on the project, recalls his emotions when finally it emerged under its own steam.

“It’s been a long job, working mainly Monday and Thursday evenings for six years, although there’ve been plenty of other jobs, too.

“It’s a fantastic machine, a real piece of history. It looks really sleek now, all green and gleaming brass.

The sense of satisfaction is unbelievable.”

Joem is now expected to spend much of the summer working at the National Railway Museum in Shildon before steaming later this year on the Tanfield Railway and at Beamish Museum.

None doubts that the Great Survivor will pull its weight. 60923 is the little engine that could.

■NELPG has open days at its Hopetown Lane premises on the third Saturday of each month between 10am and 4pm.

THE Bishop of Durham is to spend the whole of the weekend of March 12 to 14 in the Sedgefield deanery – including Sunday lunch at the street corner Surtees Arms, in Ferryhill Station which by happy chance has its own Yard of Ale brewery at the rear.

Good stuff, too.

The bishop, Dr Tom Wright, will spend Saturday afternoon in Sedgefield itself where John Williams, the curate, has been on a fact-finding mission to Zambia.

“It’s a country the size of England with only 15 Anglican clergy. I’ll never again complain about having to go to Kelloe,” says the Reverend Keith Lumdson, the area dean.

Yard of Ale, coincidentally, has also been commissioned to make a special brew for the Auckland Food Festival, to take place in the grounds of Auckland Castle. It’ll be called Bishop’s Yard, though back yard might be even more appropriate.

THREE years after the column accidentally discovered it, Isaac’s Tea Trail is stretching its legs a bit.

Isaac Holden, it may be recalled, was an itinerant tea seller – the Rington’s man of the early 19th Century – in the high Pennines west of Wearhead. He was also a lead miner and philanthropist. The 36- mile trail followed some of his journeyings.

Now, reports Tea Trail originator Roger Morris from Washington, it’s included in an Independent on Sunday section on the world’s great treks alongside trails in Tierra del Fuego, Morocco and Cape York Peninsula in Australia.

The tea trail’s a bit closer to hearth and home – “and via a good old-fashioned notice board in Nenthead,”

confirms Roger, “you were first.”

ONE of the recent columns on some of the bright shining alumni of Alderman Wraith Grammar School in Spennymoor – Wraith rovers, if ever – recalled Mr Gascoigne, the physics master. Chris Greenwell remembers Dickie Gascoigne, too – booming voice, academic gown and a very good teacher.

“I can still remember, word for word, some of the physics definitions he drilled into us. He had his targets, as you report, but happily I was never selected.”

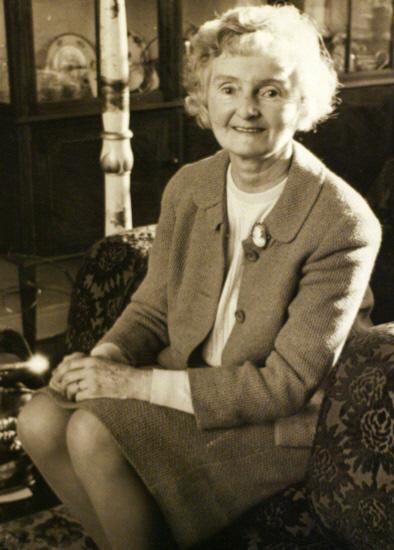

THE remarkable Mrs Thelma Denolm, whose 100th birthday we reported in early November, died on Sunday.

Daughter of William Whiteley, former Labour chief whip and longserving MP for Blaydon, she herself was made an MBE in 1979 – “services to County Durham” – served for ten years as chairman of Durham magistrates and also chaired the county probation committee.

Her husband, Durham’s director of education, died in 1954. “The first half of my life was wonderful. The second, after my husband and parents died, was really not,” she said.

“It isn’t that I haven’t been all right, I have, but there are times when you get really lonely, you know.”

She’d marked the occasion with “at home” days, advertised them in the Telegraph, received a bill for £1,351 which may have contributed to a fall the day before we met.

She was scared of hospitals, she said, didn’t like nursing homes and died, as she would have wished, in her bed. Mrs Denholm’s funeral is expected to be at St Cuthbert’s church in Durham, near her home, at 3pm on Wednesday, March 3.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article