THERE’S a letter I’ve carried around in my laptop case for the past four years.

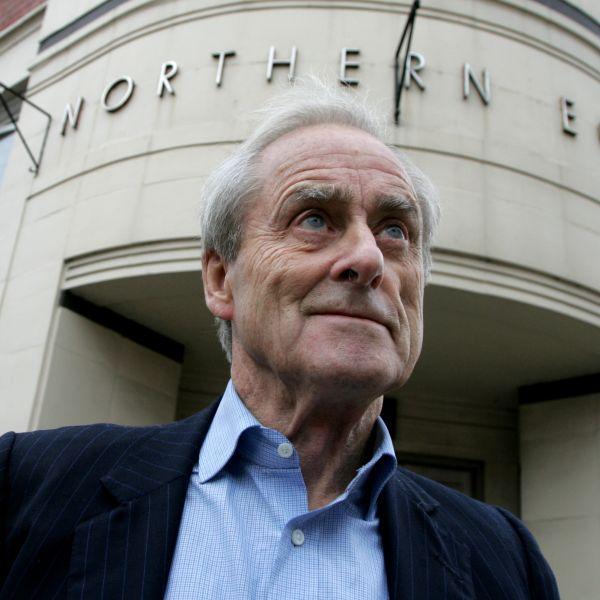

It arrived out of the blue from a Northern Echo reader called Irene, who wanted to say thank you to the paper and its legendary former editor, Sir Harold Evans, for what they had done half a century earlier.

Irene, who lived in Durham, had given birth to a child with deformities. The boy was one of the victims of a new drug called Thalidomide, prescribed to his mother to counter morning sickness.

The devastated family, like many others, felt helpless and alone – until Harry Evans, the firebrand editor of their local paper, The Northern Echo, began to write about the scandal.

“We were always Northern Echo readers, and, through the paper, we began to realise we weren’t isolated,” the mother explained. “There were others in the same position, and we started to contact each other. There was a little boy at Spennymoor, and a girl at Wheatley Hill. Just knowing that we weren’t alone, and that someone was on our side, meant so much.”

The families formed a self-help group, meeting regularly, fundraising, and sharing experiences. Meanwhile, after a trail-blazing eight years in the North-East, Harry left The Northern Echo, to join The Sunday Times.

Once in charge of what he described as a “Rolls Royce” capable of revving up the power of the press on a national scale, he accelerated his campaign to expose the shameful cover-up by Distillers, the drug company responsible for distributing Thalidomide on the NHS.

It led to a life-changing trust fund being set up for the Thalidomide families, and the letter from Irene, posted from Durham 50 years on, ended with the paragraph: “I’ll never forget what The Northern Echo and Harry Evans did for us.”

And there lies the greatness of the man. He made such an impact that, decades later, people remembered that he was on their side and changed their lives for the better.

Irene’s letter of thanks is one inspirational example of Harry’s legacy, but it was reinforced wherever I went when I was editor of The Northern Echo, between 1999 and 2016.

I lost count of how often readers wanted to talk about the time they met The Northern Echo’s great editor from the sixties. Whether I was speaking at Women’s Institutes, Townswomen’s Guilds, Rotary Clubs, or just walking down the street, the people of the North-East loved to recall when Harry Evans was their editor.

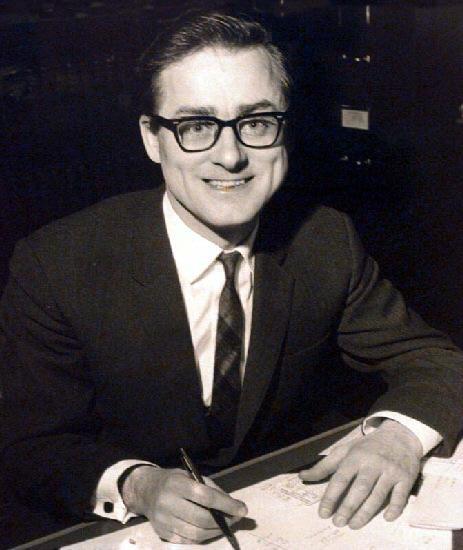

He was a gifted writer, of course, but there was much more to his success than that. He understood the value of what is now known in business circles as ‘networking’. To Harry, it simply meant getting out of the office and meeting people: listening, observing, understanding, then reflecting what was important to them in their newspaper.

There were many more campaigns on Harry’s CV, of course, not least a momentous battle while at The Northern Echo to make cervical cancer testing part of the NHS.

He’d read a three-line filler paragraph in The Sunday Times, reporting that Vancouver was expanding a programme to save women from dying of cervical cancer. Harry’s instinctive response was to question why the same wasn’t happening in Britain, and to instruct a reporter, called Ken Hooper, to fly to Vancouver straight away.

Instead, Hooper saved the owners of The Northern Echo the expense of a trip to Canada, and instead spent seven weeks buried in research in this country until he had enough ammunition for Harry to fire at the Government. Amid repeated rebuffals from Health Secretary Enoch Powell, The Northern Echo kept fighting until cervical cancer testing was finally established on the NHS.

I was lucky enough to meet Harry twice. The first time was in 2000 when he flew to England to collect an honorary degree from Teesside University. He toured The Northern Echo’s offices and was treated like royalty by the staff, many of whom, like me, had aimed their careers at the Great Daily of the North because of the towering campaigning traditions he’d constructed.

He was genuinely thrilled to hear that his old paper had recently fought a campaign to cut NHS heart bypass waiting times from an average of 12 months to three months, following the death, at 38, of Ian Weir, a father-of-two and photographer on The Northern Echo, who’d waited eight months for an “urgent” triple bypass.

“You did that? That’s fantastic – well done,” he said, punching the air.

On the way back to Darlington railway station, I asked him what advice he’d give me as editor: “Don’t take any ******* notice of the bean-counters,” he replied.

The second time we met was two years ago when I travelled to London to interview him for a BBC documentary on the future of local newspapers. We talked for more than an hour and when the discussion turned to the Thalidomide campaign, he leaned forward to thump the table with anger that Distillers and the Government should have tried to evade their responsibilities.

By then, he was a frail old man of 90, who needed to pause to gather his breath and his thoughts, but a passion for campaigning journalism still burned within him.

Many was the time I looked up from my desk at his framed photograph on the wall in the editor’s office at The Northern Echo, and wondered: “What would you have done, Harry?” Indeed, he was someone all those who followed in his footsteps looked up to.

Twenty years ago, Harry told Sue Lawley on Desert Island Discs, how his interest in journalism had been ignited as a boy: “I saw lots of Hollywood movies, and read lots of books, in which heroic journalists slayed dragons, and I thought that sounds like a pretty good job.”

Thank goodness he chose journalism as his profession, because he made the world a better place.

In his autobiography, Mr Paper Chase, his reflections on the Thalidomide campaign speak volumes about the kind of man, and editor, he was: “I’d lived with the story for so many years I kept imagining the daily lives: getting into that harness, opening a bottle with one’s teeth, holding a toothbrush between one’s toes, wondering if they’d know the joys of marriage and family life.”

He was driven by anger at injustice, so much so that he immersed himself in the story, and refused to let go until he’d won.

“My greatest strength is reckless insensitivity to the possibility of failure,” he said. In other words, just get on with doing what’s right.

Not every journalist has an inspirational letter to carry round as a reminder of the dragons that can be slayed through the power of the press, but every journalist should strive to carry on what Harry Evans stood for.

Sir Harold Evans: 1928-2020. Rest in peace

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article