In an echo of the Moat case, in 1982, police spent nearly three weeks hunting an armed gunman who had killed three people. Mark Foster reports.

PICTURES of armed police combing the countryside looking for a crazed killer conjure up memories that many would rather forget. In 1982, great swathes of North Yorkshire were enveloped with fear when an embittered SAS failure went berserk, killing two police officers and a farmer and sparking what, at the time, was an unprecedented manhunt, For 17 days that summer the sight of hundreds of armed police, hovering helicopters and TV crews from around the world converging on normally placid towns, villages and countryside became almost common.

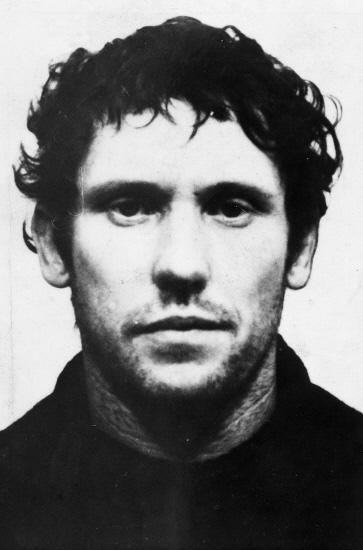

The killer was a small-time crook and bully who was born in Leeds in 1944 as Barry Peter Edwards, later changing his surname to Prudom after his mother married a man of that name.

After an unremarkable youth – apart from a spell in a borstal in Aycliffe, County Durham, for housebreaking – he developed an obsession with guns.

An outdoor enthusiast, he was rejected by the TA regiment of the SAS in 1969, apparently because of his dislike of discipline.

The death of his mother in a holiday drowning accident in 1973 deeply scarred him, and three years later, his wife left him and he went on to live a gipsy-style existence, drifting around the US with a girlfriend.

By 1982, he was back in Leeds and in January that year, the swaggering bully severely injured a motorist with an iron bar. He later jumped bail – and the terror began.

On June 17, PC David Haigh, a 29-year-old father-of-three, came across Prudom sleeping in a car at Norwood Edge, near Harrogate, and stopped to question him. Prudom produced a .22 Beretta pistol and shot him dead at pointblank range.

A huge police operation swung into operation, but it was six days later when Prudom resurfaced, in the tiny village of Girton, near Newark, in Nottinghamshire, where he came across an isolated bungalow owned by smallholder George Luckett, 52, and his wife, Sylvia, then 50.

Prudhom wanted their car and tied the couple up, but they tried to protect themselves and Prudom blasted them both in the head. Mr Luckett died, but his wife, although seriously injured, survived.

He stole their Rover and inexplicably returned north to North Yorkshire, where he was already public enemy number one.

The next day, June 24, dog-handler PC Ken Oliver, then 37, went to Dalby Forest, near Pickering, to investigate a possible sighting of the Rover by children.

He found Prudom torching the car in a clearing and the killer turned and fired at him. The officer only survived because the bullet failed to penetrate his thick clothing and he was able to raise the alarm.

The sprawling woodlands then came alive with activity, with hundreds of police searching for signs of the fugitive.

Again he escaped the net, but four days later, in Old Malton, unarmed local sergeant David Winter, a 31-year-old father, saw him walk out of the village post office.

He stopped Prudom, who he thought was an elderly farmworker. But as the sergeant started to get out of his car, Prudom pulled out his gun. Sgt Winter died from three bullet wounds.

Hundreds more police, many armed, poured into the area. At the manhunt’s height, ten forces were involved and it became the biggest armed police operation the country had ever seen, with about 1,000 officers on the ground.

But Prudom again disappeared. Various sightings were reported in the area and each was carefully checked by officers with their guns at the ready.

For the next few days, a tangible atmosphere of fear gripped the area. Malton was virtually sealed off and not a door was left unlocked.

Keys were even left in cars so the gunman could take one if he wanted without another killing.

A new element controversially joined the hunt when police called in former paratrooper Eddie McGee, who at that time ran a survival centre at Pateley Bridge, to track the killer down.

A survival guide by Mr McGee, called No Reason To Die, had become Prudom’s bible and a copy had been found among his possessions.

Eventually the fugitive did what police had feared. He took a family – pensioners Maurice and Bessie Johnson and their son Brian, then 43 – as hostages at their house in East Mount, Malton.

On July 4, he tied the family up and slipped out in the early hours, making his way to nearby tennis courts, where he built himself a makeshift shelter.

Mrs Johnson said later: “He quoted several things from the Bible. He said he would not let the police take him. He would kill himself. He said he did not intend to spend 30 years in prison.”

The family managed to struggle free and raised the alarm. Dozens of police were on the scene within minutes.

Mr McGee then stalked his prey through the suburban undergrowth, leading officers right to the makeshift bivouac Prudom had created.

The killer knew he was caught. A single shot rang out, which was answered by a fusillade of police fire.

But Prudom had aimed that first shot at his own temple. He killed himself on a compost heap.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here