Chief Sports Writer Scott Wilson looks back at the life and times of Sir Bobby Robson, one of the North-East’s greatest sporting sons

SIR Bobby Robson accomplished so much during his lifetime that it must have been all but impossible for him to select one achievement as his most cherished.

Yet two years ago, as he promoted the updated version of his autobiography, Farewell but not Goodbye, a group of journalists asked him to do exactly that.

Perhaps it would be one of the 20 times he played for his country, or the moment when, as manager, he guided England to within a penalty kick of the World Cup final?

Fans leave tributes for Sir Bobby Robson at St James' Park and a wreath is laid by Newcastle United players in his honour.

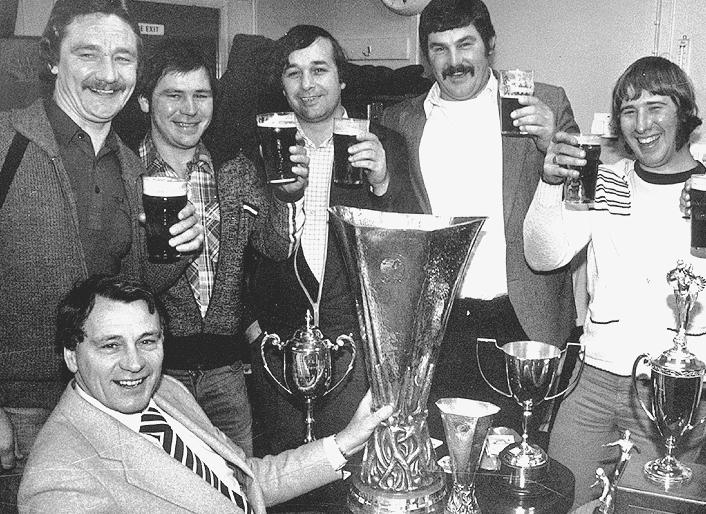

Maybe it would relate to the May day in 1981 when he lifted the Uefa Cup with Ipswich Town, or the September morning 18 years later when he was confirmed as the boss of his beloved Newcastle United?

Or would it be linked to the bestowal of his knighthood, an honour that reflected his standing at the pinnacle of the English game?

All might have flickered through his mind, but after a brief period of contemplation, Robson described something entirely different.

“When I was a 15-year-old, I went down the pit like my father and my oldest brother, Tom,” he said.

“It was only for a yearand- a-half, but I remember one day like it was yesterday.

“I had to crawl 100 yards to get to a coal cutter that had broken down.

“That’s almost the length of a football pitch, and I honestly didn’t think I could do it.

“It was just like being a soldier with snipers getting at him, and there were times when I really thought I was never going to get to where I had to go.

“Somehow, I crawled through an 18in space with thousands of tons of earth above me held up only by props.

“Even with everything I went on to achieve afterwards, I don’t really think I ever surpassed that.”

Humble, self-effacing and passionately proud of his roots. Little wonder Robson remained one of the most popular figures in English football right up to his death.

BORN in Sacriston on February 18, 1933, Robert William Robson was immediately introduced to mining and football, two of the pillars of North-East life. The first would do much to mould his character, the second would come to define his life.

Accompanied by his father, Phillip, a young Robson would travel from his family home in Langley Park to further his footballing education at St James’ Park.

Watching the likes of Jackie Milburn, Len Shackleton and Albert Stubbins persuaded him to redouble his own efforts to carve out a career in the game, even when his early attempts to secure an apprenticeship with Newcastle United ended in failure.

And, in May 1950, his efforts with Langley Park Juniors’ under-18 team paid dividends, when Fulham manager Bill Dodgin paid a personal visit to the Robson household to offer Bobby a professional career in the capital.

“My schoolboy forms had been held by Middlesbrough but the offer they made me after my 17th birthday could not compete with the riches Bill laid on our table,” remembered Robson.

“Boro proposed to pay me £4 in winter and £3 in summer, while Bill enticed me with the maximum straight away – £7 during the season and £6 in the summer, which was twice the amount I was earning at the colliery.”

So began a playing career that would eventually see Robson make 584 appearances for Fulham and West Bromwich Albion, and another 20 for England.

The most memorable came at the World Cup finals in 1958 and 1962, although the wispy wing-half was unable to prevent England crashing out of the tournaments at the hands of the Soviet Union and Brazil respectively.

“There is no escaping the sense I have that my international career was unfulfilled,” admitted Robson in his autobiography.

The same could not be said of his domestic playing days, yet Robson will not be remembered for his achievements on the pitch.

When he eventually called time on his playing career in 1968, his greatest glories were still to come.

IT was as a manager that Robson established a worldwide reputation, first with Ipswich Town and England, then with a host of Continental club sides in Holland, Portugal and Spain, and finally back in the bosom of his first footballing love at St James’ Park.

In all, he won four domestic championships, four domestic cups and two European trophies.

Even more impressively, thanks to a unique blend of talent, enthusiasm and warm affability, he was feted and loved wherever he went.

Ipswich fans erected a statue in his honour, commemorating a 13-year reign that culminated in 1981’s Uefa Cup success.

Porto supporters christened him “Bobby Five-O”

because of the number of 5- 0 wins the club recorded during his two-year tenure.

The PSV Eindhoven faithful still sing songs in his honour to celebrate the back-to-back titles Robson won in the early Nineties.

In this country, though, he is revered for two of the narrowest misses in the history of English football, 1986’s World Cup quarterfinal defeat to Diego Maradona’s Hand of God and 1990’s penalty shoot-out defeat to West Germany in the semi-finals of the same competition.

The first hurt him the most and, in later years, Robson would grow increasingly suspicious of the events that conspired against England in Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium.

“At the time I put it down to rotten luck and a bad decision that hadn’t gone our way, although I was quite clear about my feelings towards Maradona,” he explained.

“‘It’s not the hand of a god, it’s the hands of a rascal.

He’s cheated the game,’ I declared.

“It never occurred to me to suspect dishonesty on the part of the match officials.

“We were the victims of mendacity and incompetence.

“In those days, I believed that people in positions of power at that high level were straight, and that a cheating referee would always be exposed.

“Since then I’ve changed that optimistic opinion.”

Nevertheless, by guiding England even closer to the World Cup final four years later, Robson, a national boss who was once spat at when he visited St James’ Park after dropping local hero, Kevin Keegan, from the side, came to be widely regarded as England’s most successful manager since Sir Alf Ramsey.

His post-international career was just as notable, although his days on the Continent also saw the beginnings of his long battle against cancer that would ultimately prove his beating.

IN 1992, Robson was diagnosed with colon cancer and, three years later, surgeons discovered a malignant melanoma in his face the size of a golf ball.

An intrusive bout of surgery, in which his top teeth were removed and an internal plastic frame inserted to hold his face in place, ensured his survival, but his surgeon, Dan Archer, urged him to call an end to his managerial career.

“Quite frankly Mr Robson, at your age you should not work again.

Simply, people do not go back after this particular operation.”

That Robson was back behind his desk at Porto within two months was perhaps to be expected.

That he finished the season with a league title to his name, however, was remarkable even for him.

Further health scares became a feature of his later days, although his enthusiasm for football remained undimmed. So much so, in fact, that he accepted arguably his greatest challenge at the age of 66.

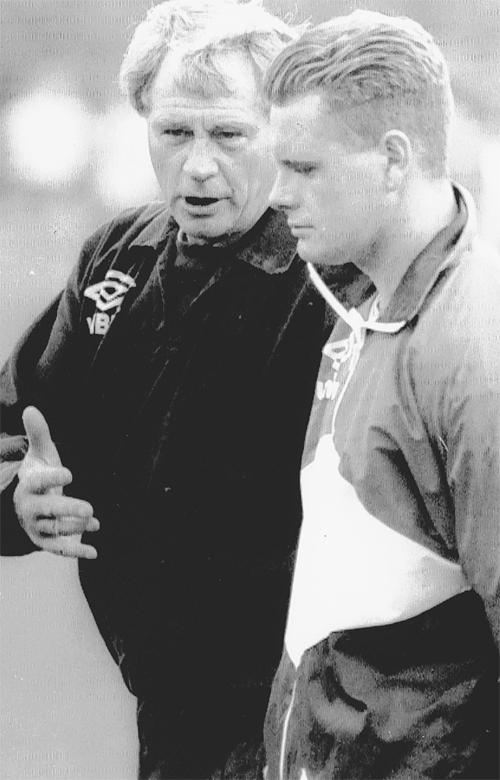

APPOINTED as manager following the resignation of Ruud Gullit, Robson was charged with the task of rescuing a Newcastle side that sat at the foot of the Premiership table.

Some viewed the job as impossible. Robson won his first game 8-0.

The following five years saw the childhood Newcastle fan enjoy some of his happiest moments, as the Magpies qualified for the Champions League on two successive occasions and played a brand of attractive, attacking football that won them admirers far and wide.

It also brought one of his biggest regrets, however, as he proved unable to end a trophy-less run that continues to stretch back to 1969.

“I’d been away for 50 years, so it seemed fanciful to believe that the circle of my life would complete itself with a homecoming at the club I had watched through dazzled eyes as a young boy from Langley Park,” said Robson.

“I had some fantastic times there, and the day when I was granted the freedom of the city by the people of Newcastle was the proudest moment of my life.”

That day came only months after Robson was sacked by chairman Freddie Shepherd, an act of betrayal from which Newcastle have arguably never recovered.

Robson refused to disappear from football entirely, taking on a consultancy role with the Republic of Ireland, but his involvement ended when medical tests revealed a brain tumour in 2006.

Further surgery followed, and the septuagenarian was diagnosed with cancer for a fifth time in May 2007.

He leaves a wife, Elsie, and three sons, Andrew, Paul and Mark, as well as a host of never-to-be-forgotten memories. His death will be mourned all over the world, but felt most keenly in his native North-East.

“My father went down the pit white and came up black,” said Robson.

“Those two colours symbolise a city’s love of football, a love that burns within me and will never fade.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here