AS everyone in Durham knows, Witton Gilbert is pronounced Jilbert with a soft G and is located two miles north-west of Durham City.

It overlooks the valley of the River Browney and unlike Sacriston, its near neighbour to the north, lies within the Durham City council area.

Sacriston, for the record is in Chester-le-Street, although Witton and Sacriston have almost merged on the border of the two districts with the onset of 20th century housing.

Witton Gilbert’s next nearest neighbour is Langley Park which, like Sacriston, is a former mining village. It lies on lower ground within the Browney valley but is across the other side of the river from Witton about a mile to the west.

Langley Park is also in a different district to Witton, being situated in Derwentside, though Langley Park’s easterly outskirts form part of Witton Gilbert parish.

This eastern part of Langley Park is Wall Nook, a little hamlet that existed before Langley Park came into being.

It lies near the Browney and was once the site of Witton Gilbert railway station.

This old station is now a private dwelling and can still be seen, but we will leave Wall Nook for another day.

Wall Nook probably takes its name from a corner of the walled medieval park called Beau Repaire Park, which gave rise to the name of Bearpark – Witton Gilbert’s next nearest neighbour, yet another former mining settlement, a mile to the south.

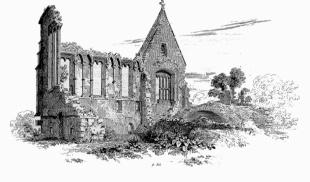

Like Langley Park, Bearpark is on the opposite side of the river to Witton, but the ruined medieval manor house of Beau Repaire is on the same bank as Witton and may be reached by a pleasant walk from Witton church.

Now we know a little about Witton Gilbert’s setting, it is important to realise that Witton Gilbert developed as a village back in medieval times.

This distinguishes it from its near neighbours because they only came into being in the 19th century as a result of coal mining. It is true that miners lived at Witton Gilbert, but Witton never really had a colliery of its own.

Some Witton miners worked at Bearpark or Langley Park, but the actual Witton Pit was at Sacriston.

So you could say that Witton Gilbert’s story begins in medieval times, but that would ignore one very significant aspect of Witton Gilbert’s past, namely the prehistoric finds that are frequently found in the area.

In the North-East, only north Northumberland and parts of Teesdale can match Witton Gilbert for its carved Bronze Age rocks.

Several rocks with simple carved cup-like features have been found throughout the area, but two very prominent slabs have been found with mysterious cup and ring markings.

One of these was found on land belonging to Witton Hall Farm and another was found in 1995 in a field belonging to Witton Gilbert’s Fulforth Farm.

Subsequent excavation of the field revealed the slab was used to cover one of two burial cists housing the cremated remains of prominent prehistoric individuals.

Carved stones and cobbles, possibly used in the for mation of a cairn above the burial chambers, were also found nearby. Cup and ring markings usually date from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age, and those at Witton Gilbert date from approximately 1700BC.

Despite its wealth of prehistory, Witton Gilbert did not come into being as a permanent settlement until Anglo-Saxon times about 2,500 years later.

Like other places called Witton, it was originally Widu-tun, meaning wood settlement, implying that it relied on the felling of wood for its livelihood.

The addition of Gilbert to the name did not occur until after the Norman Conquest, when French was the language of prominent landowners.

This explains the pronunciation of Gilbert, but the actual Gilbert in question could be either Gilbert de la Leia, who owned Witton in the 1100s, or Gilbert De Layton, who held land there in the following century.

The first of these Gilberts played a significant part in the history of Witton Gilbert and is the most likely candidate.

He was the owner of the vast Witton estate, which in those days stretched from the River Browney as far north as Beamish, Stanley and Tanfield Lea.

In fact, the last of these places was called Tanfield De La Leigh after Gilbert’s family.

The Bishop of Durham had granted this large tract of land to Gilbert around 1154 and, in a location called Witton Field near the Browney, Gilbert established a leper hospital.

Dedicated to St Mary Magdalene, this was a religious establishment founded for the upkeep of five lepers under the jurisdiction of an almoner.

Norman chapels were built nearby and one, connected with the hospital, may have stood at St John’s Green, near the River Browney, close to where a sewerage works is now situated. However, its actual existence is uncertain.

The other chapel can still be seen, as it is now Witton Gilbert’s parish church of St Michael and All Angels.

The church was substantially rebuilt in the 1860s, but some rounded Norman windows betray its earlier origins.

It was originally a local chapel belonging to the parish of St Oswald, in Durham City, but became a parish church in 1423 following a petition by William Batmanson and other Witton Gilbert residents.

Witton Hall Farm stands near the church and looks like a late 18th century farmhouse. It incorporates masonry from the leper hospital that stood here and the most obvious remnant of the hospital is a pointed window head dating from the late 12th or early 13th century.

The church and Witton Hall form the oldest part of Witton Gilbert village and are situated along a short lane running south towards the River Browney.

This little known part of the village predates the rest of Witton Gilbert, including the village Front Street, and is now separated from the rest of the village by a modern bypass road.

The buildings here are clustered along a short culde- sac known locally as the Coach Road, which is linked to Front Street by a bridge across the bypass and in next week’s Past Times it is to Front Street that we turn our attention.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article