COCKFIELD station was a mile from anywhere on the edge of a rather wild fell, yet new lockdown analysis of old counterfoils has given a fascinating insight into the life of the remote railway at the start of the 20th Century.

During the Covid-19 restrictions, Ian Mitchell occupied his time by examining three books of dockets in the archive of the North Eastern Railway Association to create a picture of the people who lived and worked at Cockfield between 1901 and 1911.

Cockfield station on an Edwardian postcard

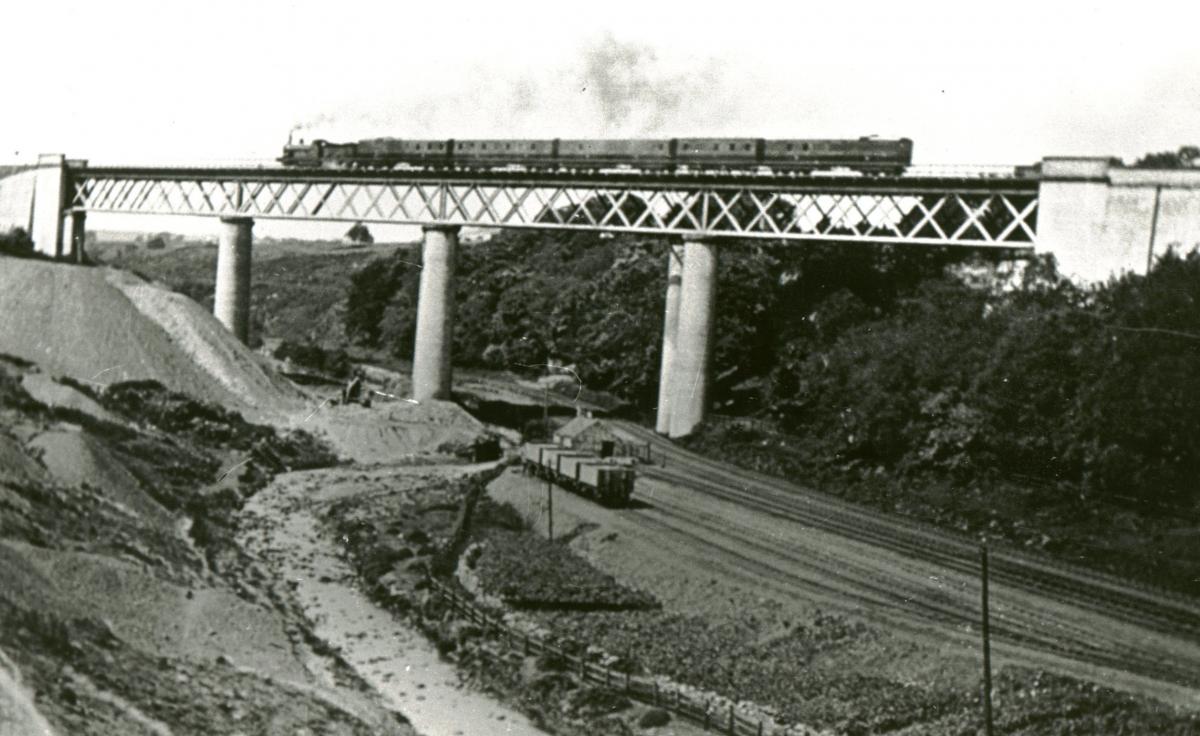

The station, which is a mile from both Cockfield and Butterknowle, opened in 1863 on the Bishop Auckland to Barnard Castle line. The line’s main purpose was to transport Durham coking coal to the west and bring Cumbrian iron ore back, but even so, six passenger trains a day in each direction stopped at Cockfield.

Except on a Sunday. There were no trains on a Sunday.

But on holidays, there were more trains: “specials” brought visitors into Cockfield so they could attend big events at nearby Raby Castle like the annual Cottage Flower Show, and summer excursions took day-trippers away from Cockfield to places like Keswick, Windermere or Redcar and Saltburn (where, of course, the railway tourists stocked up on crested china souvenirs).

In August 1900, there was even a royal train at Cockfield as the Duchess of York – later Queen Mary – was collected after her stay at Raby and taken to Durham.

Looking through Cockfield station towards Barnard Castle

Nearly 40,000 passengers a year used Cockfield station in the first decade of the 20th Century. As the population of the parishes of Cockfield, Butterknowle and Woodland was 6,619 (today it is 3,498), many local people must have been frequent train travellers.

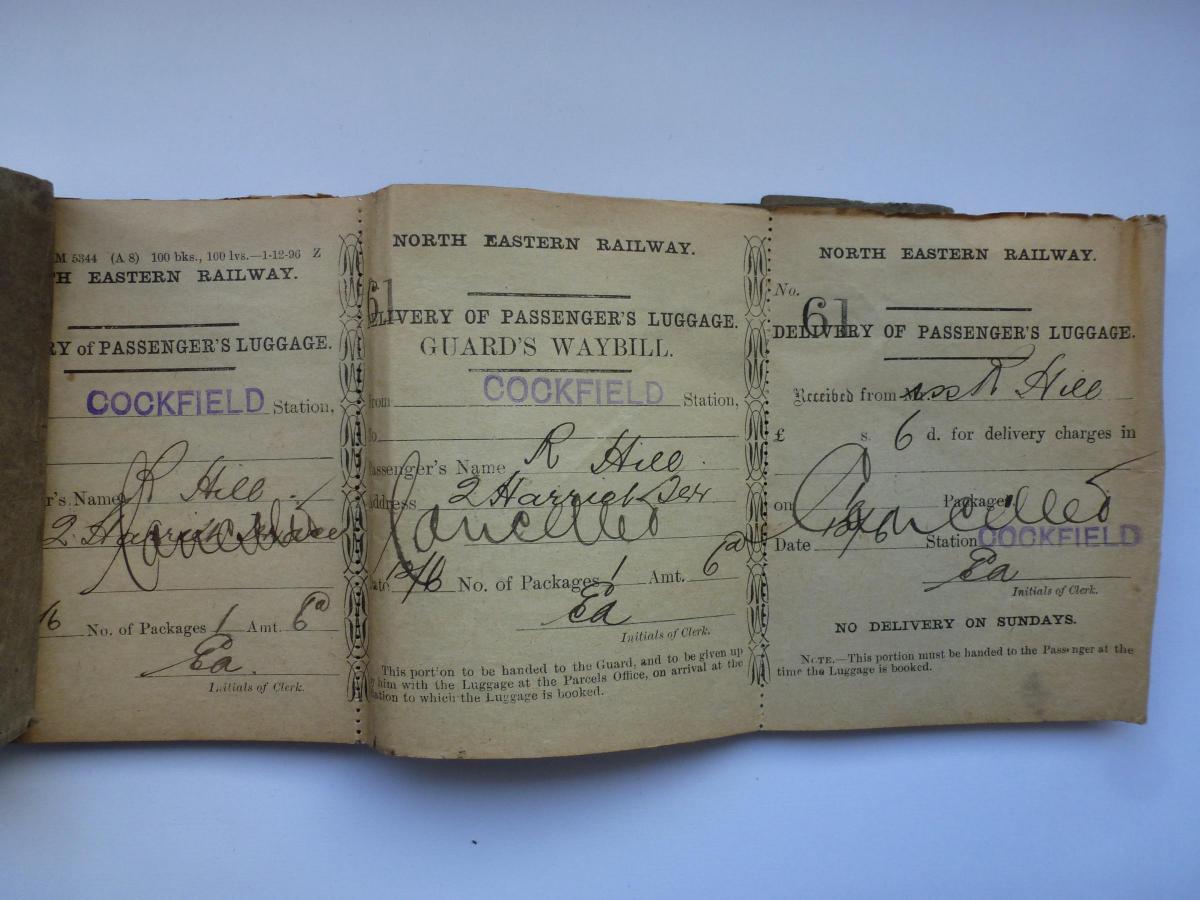

An unusual passenger's luggage delivery counterfoil from the NERA archive which is complete because the sender, Miss R Hill, cancelled the delivery. The right hand portion should have been given to the passenger, the central portion would have gone with guards on the train with the luggage, while the left hand portion would have remained at Cockfield station. Why did Miss Hill change her mind and cancel the delivery, which was set to cost her 6d? And where is 2 Harriet Terrace that she was planning to send it to? Perhaps we shall never know

A book of passenger luggage delivery counterfoils shows how keen they were on their holidays, particularly in July and August each year. These holidaymakers sent their luggage on ahead to their boarding house in Redcar High Street or even Douglas on the Isle of Man so it was ready for them when they arrived; John Teasdale, the Copley grocer, sent a perambulator to Morecambe in preparation for his family holiday.

All this railway activity required a small army of railway workers. The Cockfield stationmaster for 35 years until he retired in 1913 was Stephen Elcoat, who earned £97.50-a-year – equivalent to £40,900 today. He was born at Redworth, near Shildon, joined the railway at the age of 15, married Mary from Cockerton and worked his way up to occupy the Cockfield stationmaster’s house, for which he had £14 1s 8d deducted from his year’s salary.

Stephen and Mary had six children and were assisted by a live-in servant. At least three of their children also became lifelong railway workers.

At the station, Stephen had at least 10 people working for him: two clerks, on £60-a-year each; six signalmen, on £58.93-a-year, and controlling mainline traffic as well as access to the colliery yards; plus two platform porters on £34.45 each, which Ian works out is equivalent to £28,890 today.

Between them, they dwelt with two fatal dramas during the decade: in 1905, a man with epilepsy collapsed and died on the platform, and in 1908, a woman’s body was found on the tracks. She appeared to have taken her own life.

Cockfield Fell station derelict in 1968 and, below, as it is today (Picture: Elaine Vizor)

Because of the station’s remoteness, nine railway houses were built on the edge of the fell. Although the station closed to passengers in 1958, and the tracks were soon lifted, those houses can still be seen, as Memories 611 told.

Now, because of Ian’s lockdown investigations, we have a detailed picture of life, and death, at this lost station. Ian had written his findings into a booklet which is available to download for free from the NERA website, even to non-members. Go to ner.org.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here