IN its New Year edition of 100 years ago, the Echo’s sister paper, the Darlington & Stockton Times, devoted a deep column to an unnamed journalist’s experiences during the First World War. As well as providing a fascinating first-hand read, the account tells how Darlington had become a “godparent” to the French village of Mercatel which had been devastated by the conflict.

Mercatel is near Arras, where our journalist arrived in 1916 to find a town destroyed by shellfire. Mercatel, just four kilometres away, was still occupied by the Germans, and the two armies were so close they were exchanging sniper fire.

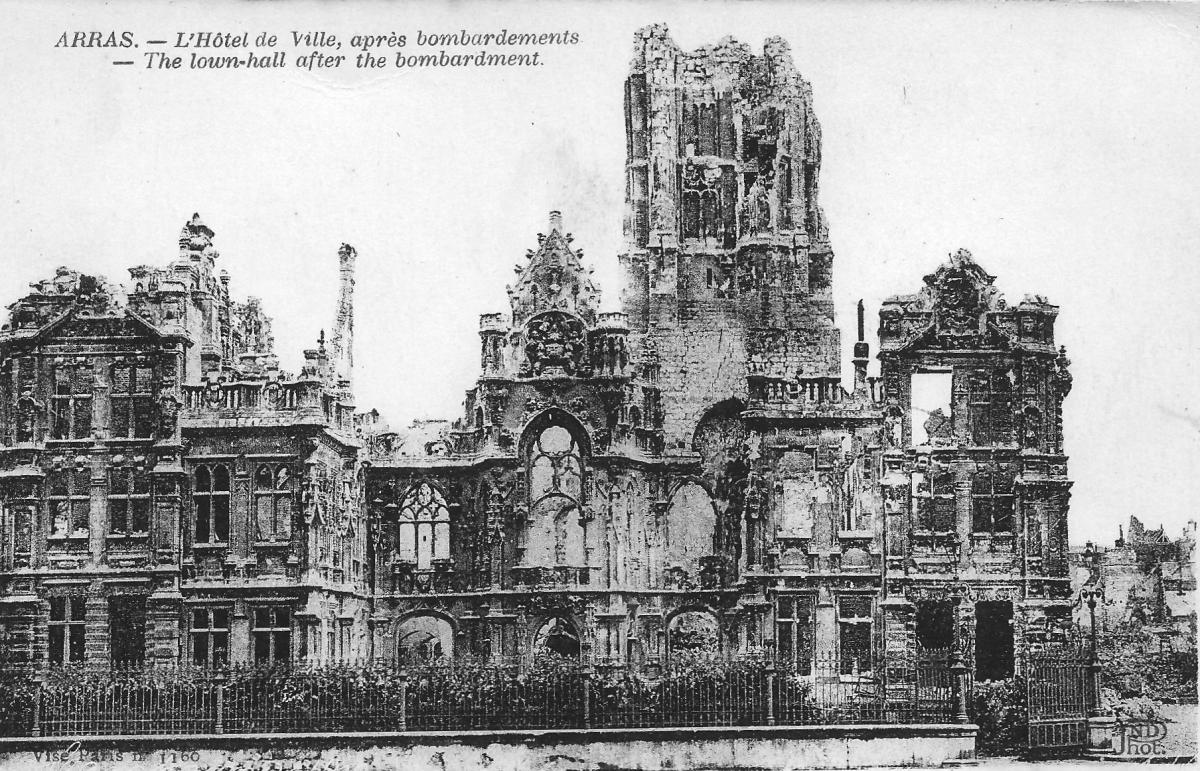

The First World War devastation at Arras

During the day, the British soldiers and the 1,000 surviving civilians cowered in cellars, hoping the ruined buildings over their heads would not collapse in on them.

“No one was seen in the centre of the streets for the obvious reason that those filthy Bosche observation balloons glared at us all day long, but when night set in, what a transformation,” wrote the D&S reporter. “Out from our cellars we poured in our thousands, and for the brief space of two hours, apart from the usual interruptions from the enemy, life was almost sweet. So thronged were the streets with khaki that one could almost picture oneself in an English town were it not for the entire absence of light and the female element.”

Arras under bombardment during the First World War

Our journalist, being an erudite soul, walked around, gawping at the ruined architecture of the cathedral and town hall.

“The less artistic, who were in a majority, preferred the more stimulating pleasures of gulping down in record time large quantities of peculiar liquids of rather doubtful origin, and losing, and less frequently gaining, their fortnight’s pay at crown and anchor,” he wrote.

When the Germans were evicted from Mercatel in 1917, our man remembers walking in a daze through the village looking at the desolation. All the houses, in which 400 people had once lived, were just piles of rubble and “the church had disappeared with the exception of one wall, which seemed to raise itself in protest to the heavens above”.

On the edge of the village, he found a temporary British cemetery from the early days of the war which had been surrendered to the Germans.

“The tide of war had so flowed that the poor little cemetery, containing about 50 Britishers of all ranks, had for a few months been in the centre of no-man’s-land,” he remembered. “As a consequence, graves were ploughed up with shellfire, crosses were smashed, and other things had happened which it will be discreet not to mention.”

The restored church at Mercatel, L'église Saint-Léger de Mercatel, by André Lemoine, from Wikipedia

He was heartened that Darlington had “adopted” Mercatel through a little-known organisation called the British League of Help for the Devastated Areas of France, which had been founded by Lady Bathurst. She had been shocked by the destruction she saw on a tour of the battlefields and urged mayors and civic leaders in British towns to become “godparents” to stricken places.

Many towns refused to join her ladyship’s unofficial scheme, saying they had their own devastation and plenty of war victims to deal with, but about 122 French towns and villages were adopted.

Darlington is the only godparent listed in the North East except for Newcastle which taken on Arras.

Rather oddly, one group, The School of Ladies Hairdressers, is listed as having adopted the village of Lagincourt-Marcel. They chose it because its name contained a reference to the “marcel wave” which was the styling fashion of the 1920s.

The British godparents raised money to repair schools, hospitals, water towers and town halls. In Albert, there is still a Rue de Birmingham in recognition of the second city’s generosity and in Bapaume, near Arras, there are still “les maisons de Sheffield” which the steel city built for French war widows.

It is not clear why Darlington chose Mercatel nor what it contributed.

The D&S veteran wrote: “The fact that Darlington has ‘adopted’ the little place will be a godsend to those worthy peasants, whose life is simply one round of unremitting hard work.” They were, he said, removing war debris from their farmland to make it productive again.

He concluded: “It may be hoped that as a result of help received from Darlington the little place may be once more securely set on its feet.”

We’d love to hear from you if you can tell us anymore about Darlington and Mercatel.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here