THOMAS WRIGHT was a boy with a speech impediment from Byers Green who reached for the stars. From humble beginnings in a County Durham backwater, he rose to win a sky-high reputation as a mathematician, navigator and an astronomer – he was the man who first explained the milkiness of the milky way.

And now the site where he was born 310 years ago, and where his life came full circle in 1786, has been marked with a blue plaque by Durham County Council.

Thomas was born on September 22, 1711, in Pegg’s Poole House in Byers Green, which is between Spennymoor and Willington. His father was a carpenter and from the age of eight, he attended King James I Grammar School, in Bishop Auckland.

Because of his speech impediment, he was given extra maths tuition, rather than languages, by teacher, Thomas Munday. Wright was so inspired that he could be found hiding in haystacks poring over books. His father even burned his books because he feared he was becoming too bookish.

Aged 14, Thomas became an apprentice to clockmaker Bryan Stobart, but stumbled upon a scandal: when the Scots Greys dragoons were stationed in Auckland Park, he became aware that Mr Stobart’s maid was seeing "ye captains man".

The maid wished to keep the affair quiet, so "she came to Bed" with Thomas, which so flummoxed the naive 18-year-old that he confessed all to Mr Stobart.

Mr Stobart did not believe him, and with the captain's man threatening violent revenge, Thomas fled from Bishop Auckland. He headed for Ireland, but on reaching Barnard Castle turned back and went to Sunderland where he joined the crew of a ship.

However, his first journey to Amsterdam was so rough he decided he was not cut out for life at sea.

Instead, aged 20, he set up a "mathematicle school" in Sunderland to teach sailors the art of navigation.

He fell in love with the beautiful daughter of a clergyman, a Miss E Ireland, but she had other wealthy suitors and her father went to great lengths to keep her away from Thomas – "2 rich rivals and Miss locked up" was how Thomas described his predicament in his diary.

He fled once more – this time to Barbados. But he only reached London.

He was, though, beginning to make a name for himself. He had been publishing an almanac, which told sailors about the phases of the moon and the times of the tides. He was building sundials, predicting eclipses and compiling a Pannauticon – a book by which a sailor could navigate by the stars anywhere in the world.

In London, he built an enormous brass orrery – a working model of the universe – and delivered lectures on astronomy at Brett’s coffee house. He was a curiosity: a County Durham yokel with a speech impediment and a headful of learning and theories, and skilled, intricate fingers.

Such was his reputation that in 1742, the Tsarina Elizabeth of Russia offered him £300-a-year to become Chief Professor of Navigation at the Imperial Academy in St Petersburg. Thomas turned it down, asking for £500-a-year because he was developing a lucrative sideline: redesigning the gardens of his upper class patrons.

His style mixed ancient Greek with high Gothic. It matched perfect symmetry with wildest eccentricity. He laid out immaculate flowerbeds with serpentine canals running through them.

He built summerhouses, temples, menageries and even stibadiums – rounded, Romanesque seats – and decorated ceilings with models of the universe.

Thomas had the misfortune to go out of fashion quite quickly – many of the stately gardens and homes he redesigned in the 1740s and 1750s were redesigned in the decades afterwards by Capability Brown who preferred more formal, less eccentric designs – so Thomas’ greatest surviving success is Shugborough, in Staffordshire. Now owned by the National Trust, it features Thomas’ revolutionary bow windows – windows that are rounded to follow the path of the sun and so catch more of its rays.

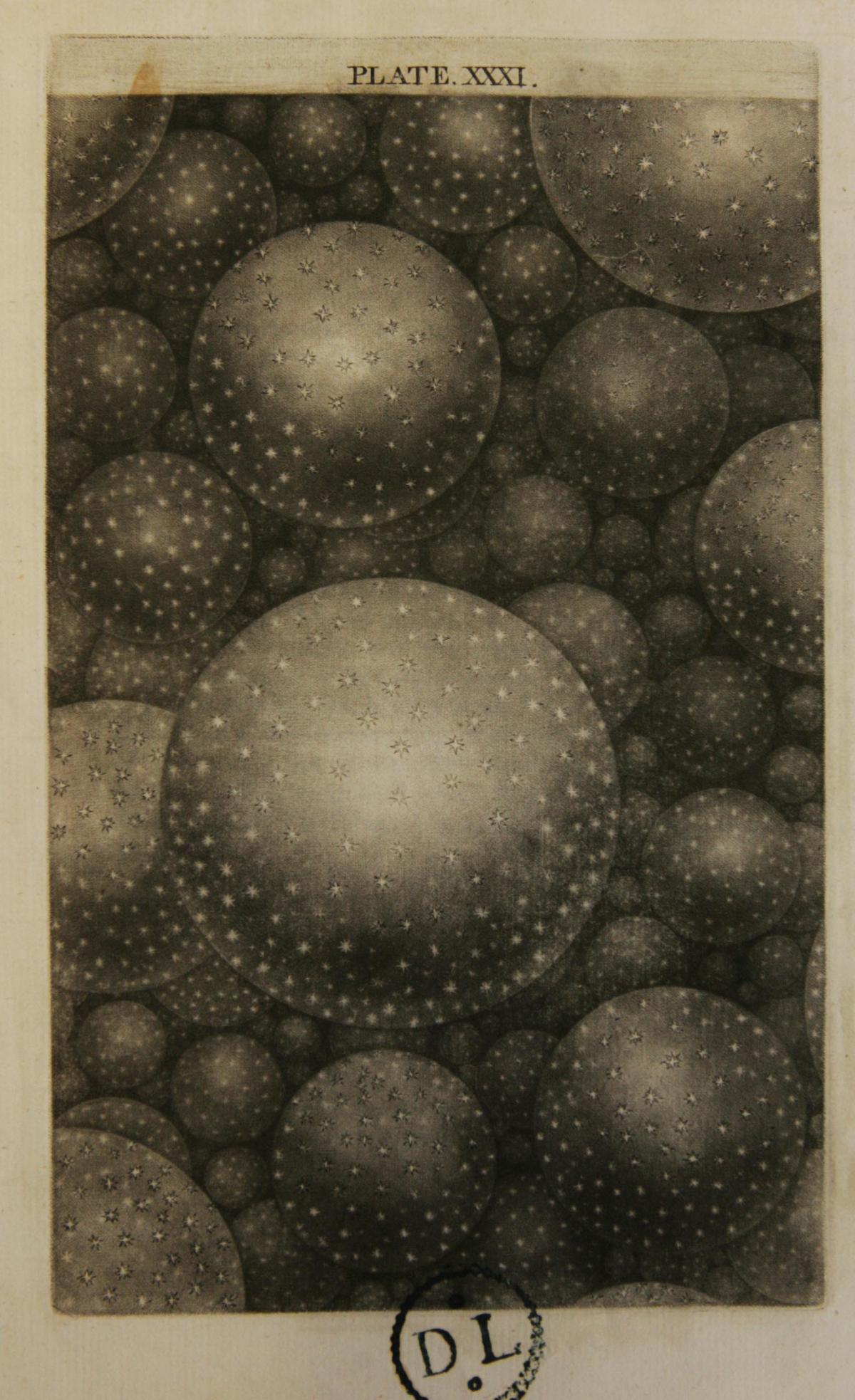

His greatest work was published in 1750: An Original Theory Or New Hypothesis of the Universe. In it, he identified the nature of Saturn's rings, understood the paths of comets and suggested that some stars were brighter than others because some were further away. This led him to be the first astronomer to describe the universe as disc shaped, rather like a millstone.

The Milky Way, he explained, was "an optical effect due to our immersion in what locally approximates as a flat layer of stars".

This was mind-boggling stuff that inspired the German philosopher, Immanuel Kant.

Many of Thomas’ ground-breaking discoveries are now regarded as correct although, in truth, he had stumbled upon many of them while attempting to prove that God physically existed at the centre of the universe and was surrounded by a Gulf of Morality.

Proper academics regarded him as a curious, thought-provoking amateur.

In 1755, he bought his birthplace in Byers Green from his brother for £20. He "pulled the old house down", but kept the timbers, doors, 100 loads of stone and 1,000 bricks which he built into his new home, along with 45,000 new bricks and 50 loads of stone (the mathematical mind likes to record these quantities).

Thomas Wright's "villulet" in Byers Green shortly before it was demolished in 1967

He said it was too modest to be called a villa, so he referred to it as a villula or villulet. Still, though, he based it on Pliny's designs and laid out his orchards and gardens with his customary style. The ceilings were covered with paintings of the heavens, and his staircase featured an accurate model of the universe with all the planets in their correct positions in the ballustrades.

In 1762, aged 51, he retired from the wider world to Byers Green "to finish my home and prosicute my studies".

On November 20, 1763, someone called Elizabeth Wright who was living in the villulet – possibly a housekeeper who coincidentally had the same surname or a distant relative – bore the unmarried Thomas a daughter, also called Elizabeth.

When not busy with his thinking, reading, gardening and horse-racing – he laid out "the finest piece of raceground in the North of England" near Byers Green – he designed a fabulous palace in St James' Park, London, for the king.

Unfortunately, His Majesty was doing up Buckingham Palace at the time, so Thomas' ideas never left the drawing board. Instead, he designed the deerhouse in Auckland Park, and the Auckland Castle north gate on the A688, and he sorted out the lakes at Raby Castle.

Thomas Wright's deerhouse at Auckland Castle, built for £379 in 1757.

Thomas Wright's observatory in Westerton in 1955

In 1778, Thomas started work on what is really his most impressive monument. The village of Westerton is a couple of miles south of Byers Green and, at 200 metres above sea level, it is the highest spot in south Durham. In the centre of the village, Thomas started work on an observatory, based on a design for a circular hilltop folly that he had published in his 1744 book, Remarkable Ruins of Antiquity.

It probably wasn’t meant for astronomical observations, but he certainly made meteorological observations from it, and possibly topographic observations of the lie of the land for the maps he loved drawing. Apparently from its top you can see the tower of Durham Cathedral and the towers of York Minster.

Thomas may not have lived longer enough to see the towers because he died, aged 74, in Byers Green on February 25, 1786, with the tower not completed.

He was buried in St Andrew's, Auckland, (Elizabeth, his daughter, joined him two years later, aged 23).

Most of Thomas' library was purchased by George Allan, the antiquarian who lived in Darlington's Blackwell Grange. He presented several of Thomas' books to Darlington library, including a copy of 1750's Original Theory – it is quite a thrill to sit with the book and think that 250 years ago Thomas himself may well have pored over it when it arrived from the printers.

But while we have his books and, of course, his fabulous tower (above), which was finished after his death, his “villulet” is gone. His gardens, with his carefully manicured views over the valley of the Hagg Beck, had the terraces of Ghent Street and Vine Street built on them in Victorian times, and the “villulet” was demolished in 1968. Even Thomas’ astronomical staircase was destroyed.

At least now, though, the county council has put a blue plaque on the property that replaced it.

The official unveiling of the blue plaque honouring astronomer Thomas Wright in Vine Street, Byers Green. From left, Professor Richard Bower, of Durham University; Sara, Lucifer and John Courtley, who live in the property where the blue plaque has been

HAS anyone ever been in Westerton observatory? What’s it like? What can you see from the top? Can it be opened to the public for one day?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel