“ON August 12, we saw a notice on a tree – “Bomb dropped on Japan”. Later a second one, in the Indian camp on August 14. Shots went up. The war was over,” said Les Butler, who celebrated his 100th birthday this week in Sedgefield.

He was out in Burma in 1945 as the news broke of nuclear bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and then the Japanese – his enemy – surrendering.

“But at home, the war had been over for three months and I had a daughter 14 months old,” he said. “Yet I had to stick it out until September 1946, waiting for my embarkation number to come up. It didn’t feel fair, somehow.”

Les was born in Birmingham where he saw the first effects of the war: as he cycled to work, he saw bodies laid out under white sheets – a bomb had flukily fallen through the entrance of an air raid shelter, killing all the cinemagoers waiting inside.

In 1941, he was posted to Hardwick Camp in the north end of Sedgefield to man the searchlight batteries seeking out enemy aircraft.

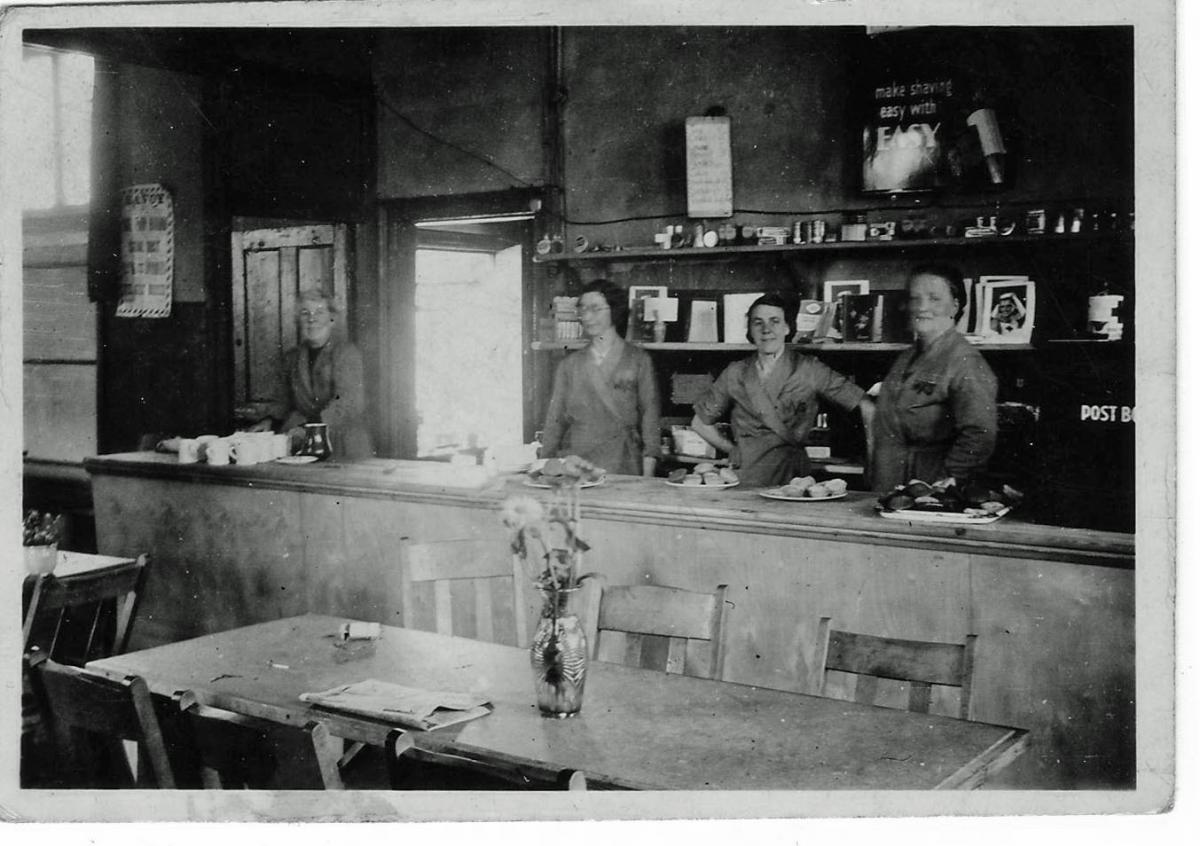

Sedgefield was largely cocooned from the war, but it was still a busy place: as well as the 200 men in Les’ camp, there was another army camp opposite the racecourse, a Red Cross hospital was built on the road to Fishburn, Land Army girls were house in Spring Lane, and there were German and Italian prisoners working in the fields all around.

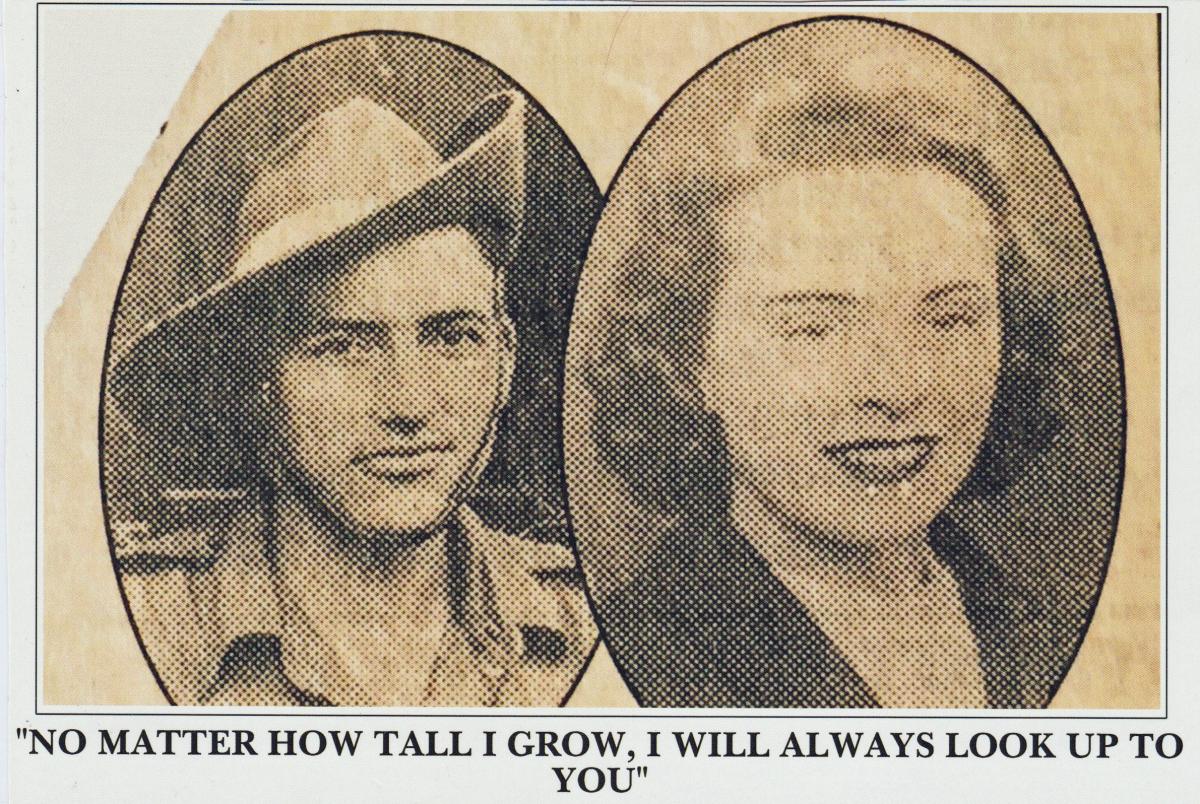

Les met Marjorie from the village, and they married at St Edmund’s Church in 1943. When he sailed for India in 1944, she was six months pregnant.

Life changed very quickly for the father-to-be. He’d swapped the comparative calm of the cocoon for the fear of the frontline – the American pilots who flew them into Burma ordered them to get out of their planes quickly because they were worried about the nimble tanks of the Japanese – and he’d swapped the County Durham climate for the heat of the east.

“It was very hot and we were given fine linen water ‘shaggles’, which kept our bottles cool in the heat,” he said in his memoires, which have been recorded by Norma Neal of the Sedgefield history society. “The lake at Meiktila looked very inviting in this heat, but there was no way for a dip – too many dead Japanese in there.”

He was with the West Yorkshire Regiment, and it was their job to push the Japanese south through Burma – now Myanmar – and out into the Indian Ocean.

“We came upon a high hedge,” he said. “Three of us were facing it when the Japs burst through, coming straight at us. I thought I was finished, but an old hand to our left let go a burst of machine gun fire. Saved our lives.

“Then, as we went through a hedge, a grenade popped up from a foxhole. We ran fast to dodge it, then, looking back we saw one of our Indian friends lob a grenade right in. That finished him off.”

Conditions were rough. Malnutrition led Les to develop green ulcers on his legs, which in many cases led to amputation. “It was my lucky day,” he said. “A male nurse came to me and said the first batch of penicillin had arrived and they were going to try it on my sores. They put a gauze cover over them and sprayed every four hours. The miracle happened and I was left with thin scales of skin.”

He recovered, and made it to Rangoon on the southern tip of Burma, where he learned that was coming to an end.

He didn’t get home, though, until October 1946 – more than a year after the Japanese had surrendered – and his train pulled into Ferryhill Station one night after midnight.

“I thought I would kip the night in the waiting room,” he said, “but a policeman and a porter said it was not allowed. I was told to leave my kit, walk home and come back for it the next morning.

“So I walked the six miles to Hardwick Park Kennels, woke up my wife’s family and was greeted with lots of enthusiasm. It was lovely to be home with my wife and two year old daughter.”

For his 100th birthday, Les’ family named a star after him near his sign of Taurus. He then spotted I’m A Starman was running in the 4.30 at Warwick, put a couple of pounds on it, and it came in at 3-1. That’s the sort of day of which there should be many happy returns.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here