ON February 13, to mark his first year as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak tweeted a picture of himself as a small schoolboy, knee-length shorts and oversize cap, on his family doorstep alongside a picture of himself, sharp coat and smart tie, on the doorstep of No 11 Downing Street.

“Growing up, I never thought I would be in this job (mainly because I wanted to be a Jedi),” he wrote beneath the pictures.

The tweet fits into the story of his meteoric rise and today, less than six years after becoming the MP for Richmond, the 41-year-old Star Wars fan is going to present a Budget that, with little fear of exaggeration, could turn out to be the most important for a generation. He has to juggle borrowing and spending hugely – £271bn since March and rising by the day – to keep the economy afloat today with the need to raise taxes so that tomorrow the economy is not sunk by overwhelming debts.

No Chancellor, just 13 months into the job, can ever have presented such a momentous Budget.

Mr Sunak was born and grew up in Southampton, the grandson of Indian immigrants, and the son of a GP and a pharmacist – his is a classic Tory story, reminiscent of Margaret Thatcher’s, of hard work above a shop leading to political success.

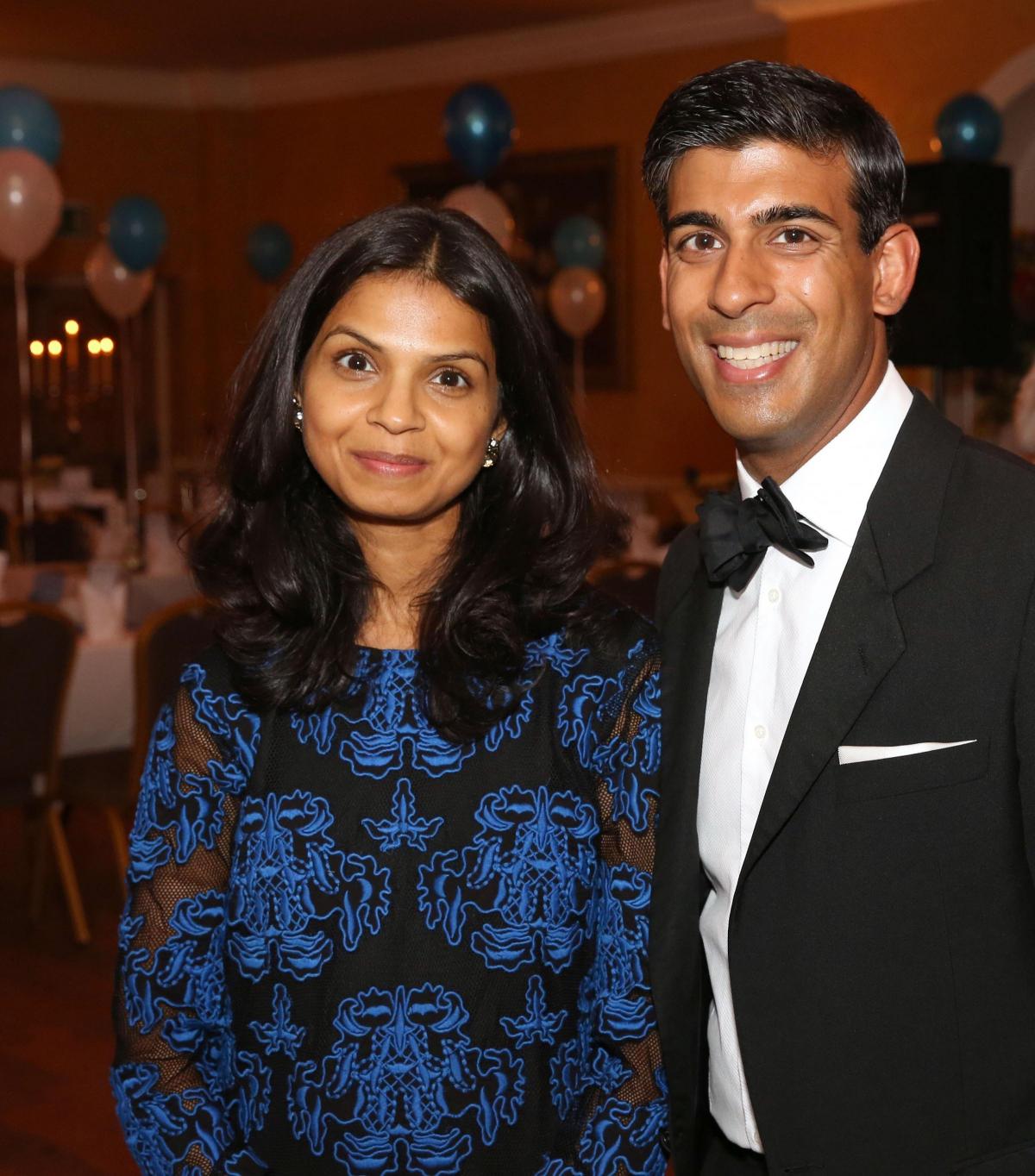

He went to Winchester College, Oxford University and then Stanford University where he met his future wife, Akshata, who is the daughter of Indian billionaire, NR Narayana Murthy, co-founder of the Infosys technology company.

They married in 2009 in a two-day Hindu ceremony in Bangalore, attended by Indian celebrities, including former cricket captain Anil Kumble. They now have two daughters.

Mr Sunak, 39, made his own fortune in finance, working for Goldman Sachs and as a hedge fund manager. Commentators refer to him as “by far the richest member of the British Cabinet”, and he has a £10m property portfolio which includes his £1.5m Georgian mansion to the east of Northallerton which features an ornamental boating lake set off by a 12th Century church.

He arrived out of the blue in North Yorkshire in late 2014 to vie for the safest seat in the country which William Hague was vacating.

There was a natural local successor in Wendy Morton, chair of the local Conservatives, but at the selection meetings, Mr Sunak “blew all the other candidates out of the water” with his sharp mind and ready smile.

In the wider constituency, there was great scepticism about such an outsider being parachuted in – one Yorkshireman is said to have confused him for someone who could trim his privet.

“The Maharaja of the Dales” does stick out like a sore thumb, but there are stories of how he turns it in his favour. He described himself to the Yorkshireman whose privet needed trimming as the same as William Hague, only with a better tan, and on another occasion he is said to have jokingly pointed out how he and his wife make up the entire immigrant population of the constituency.

He won the constituency over in those early years by hard work and ubiquity. He appeared at farmers’ markets, immersed himself in the intricacies of milk pricing and was photographed beside drystone walls wearing artfully muddied wellies – they were city blue to begin with but as he has become more Yorkshirified, they have become farmerly green.

His approachability and enthusiasm won over many doubters – in 2017, he took 63.9 per cent of the vote, more than any Tory in Richmond since 1959.

When the Brexit referendum was called, Mr Sunak was quickly and publicly in favour of leaving the EU – a brave position for an ambitious backbencher in a party led by David Cameron and in which Mr Hague, a remainer, was still hugely popular locally.

Mr Sunak came out at the same time as Michael Gove and Boris Johnson, and when Cameron heard, he reportedly said: “If we’ve lost Rishi, we’ve lost the future of the party.”

Mr Sunak took his message to his constituents in a series of town hall question and answer sessions (I chaired a couple of them). Lean and super-confident, he marshalled his arguments persuasively and with an internationalist slant, but was honest enough to admit there might be a downside.

It was a close run thing, with Richmondshire voting 57 per cent to leave and Hambleton 54 per cent, but it was clear that this former hedge fund manager knew which side to back in a gamble.

Similarly, in spring 2019, he gambled early on backing Mr Johnson’s leadership bid. When Mr Johnson shied away from the TV debates, Mr Sunak deputised: articulate if a bit autoscript wooden, but still safe.

Indeed, when Mr Johnson visited The Northern Echo in December, one of his entourage said they were taking their money off Chancellor Sajid Javid as the first ethnic minority Prime Minister and buying shares in Mr Sunak.

So when Mr Javid fell just over a year ago, Mr Sunak seamlessly slid into No 11 Downing Street.

He is the yin to Mr Johnson’s yan. Just as Mr Johnson looks scruffy and unkempt in whatever he wears, Mr Sunak is always thin and immaculate; just as the Prime Minister doesn’t do details, Mr Sunak is immersed in them.

He has had a good pandemic, despite Britain suffering a deeper downturn than many countries and despite his headline-grabbing Eat Out to Help Out scheme increasing the infection rate by up to 17 per cent, according to one university study.

But so far it has been spend, spend, spend. Today he has promised to level with the British people – can his popularity possibly survive the tough decisions, and the pain, that lie ahead?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel