Twenty-five years after it was founded in a garage, Amazon has obliterated the global delivery market. As it prepares to open a massive operation just outside Darlington, Luke Rix-Standing looks at the man behind the company that changed the face of retail.

THERE are almost as many opinions on Amazon as there are products in its warehouses. Ask a time-poor consumer, and they might describe an ultra-convenient, customer-centric service, supplying their every need with metronomic regularity. Ask a high-street retailer, and Amazon personifies predator capitalism, using market heft to decimate opponents.

Perhaps the most mercurial opinion belongs to Amazon founder and world's richest man Jeff Bezos, who has repeatedly claimed that large companies have a lifespan of around 30 years, and Amazon faces an inevitable and imminent demise.

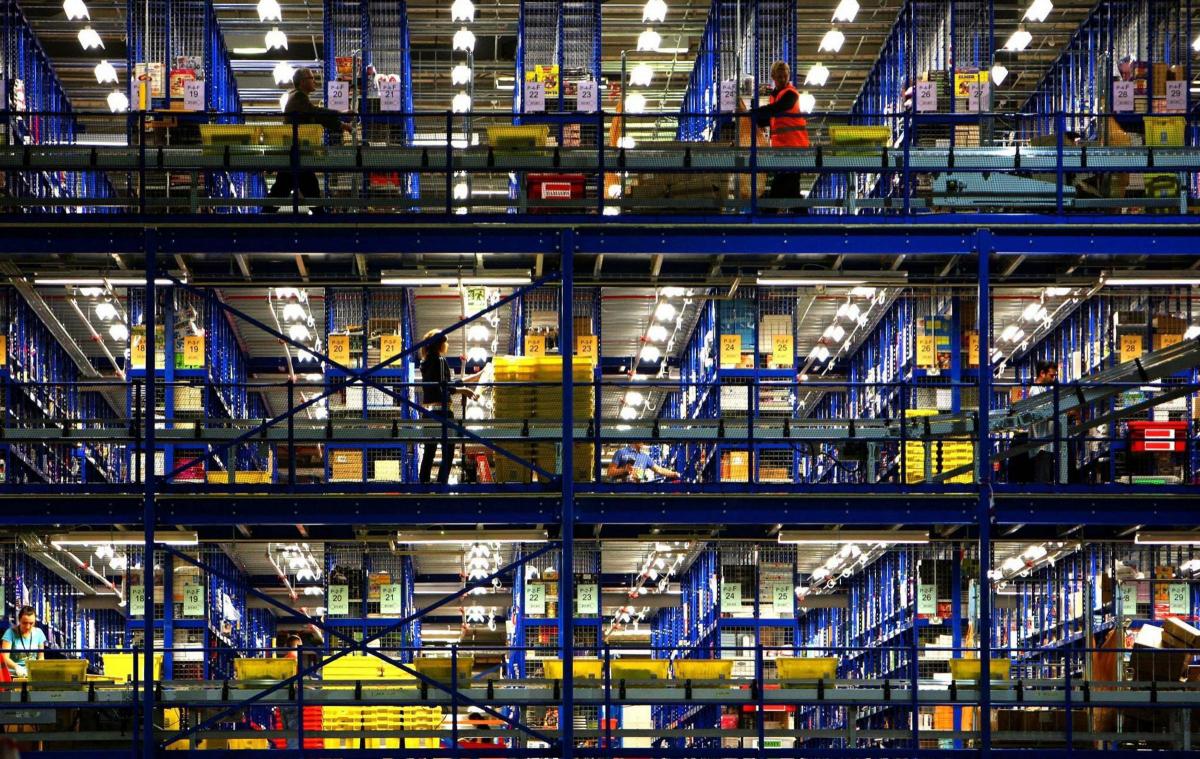

Whatever your views, Amazon is part of the furniture for billions worldwide. Locally, later this year, it will open a massive fulfilment and distribution centre at Symmetry Park, just outside Darlington, bringing thousands of jobs to the area. So who is the man behind this phenomenon?

Even as a teenager, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos was never afraid to dream a little bigger. At his 1982 high school graduation, the 18-year-old valedictorian informed his peers he intended to "build space hotels, amusement parks... and colonies for two or three million people orbiting around the earth".

Born in New Mexico, raised in Texas and schooled in Florida, his working life had begun in his local McDonald's two years earlier - an experience he later credited with teaching him essential management skills.

A born problem-solver with an acute sense of the long view, he studied computer science and electrical engineering at Princeton, and promptly set about climbing the greasy pole of Wall Street after graduating. With an outrageous IQ, a restless disposition and no girlfriend, Bezos famously established an analytical flow chart for dating, calibrated to select and attract suitable partners.

It's hard to say how much his 'model' helped, but he did meet his now ex-wife MacKenzie during this time. They split earlier this year after 25 years of marriage (there reportedly wasn't a prenup).

Perhaps more than anything, Bezos is a risk-taker, with Amazon possibly his greatest gamble. The American dream made flesh, he left his cushy hedge fund job and headed west to make his fortune, setting up an online bookstore nobody believed could succeed, settling on the name Amazon for the disappointingly mundane reason that the eponymous river is big, and carries lots of stuff.

The business began with books, but Bezos was already aiming more at Walmart than Waterstone's, and went to great lengths to structurally understand how products could be ferried around the country. From the very beginning, the Amazon philosophy was forensically centred on customer experience.

The company took off very, very quickly; within its first month the site received orders from all 50 US states and 45 countries. Bezos promptly hired billboards to drive past Barnes & Noble stores emblazoned with the question: 'Can't find the book you wanted?'

Amazon's working methods have always been unorthodox: PowerPoint presentations are banned, every employee spends two days a year on the customer service desk, and idea pitches must never be more than six pages. "You can work long, hard or smart," Bezos told a meeting of shareholders in 1997, "but at Amazon.com you can't choose two out of three."

Always intended to sell (quite literally) everything, Amazon quickly became a jack of all trades. Own-brand products include the Kindle - an electronic library slowly eviscerating traditional books - and the inter-connected empire that is Amazon Echo, and its helpful mascot Alexa.

Amazon spends money to make money, and acquisitions range from online shoemaker Zappos to supermarket chain Whole Foods, audiobook service Audible, and live-streaming website Twitch. Masters of market manoeuvring, many of these moves were meant more to price out competitors than return instant profits.

One transaction stands out from the crowd - in 2013, Bezos completed the personal purchase of veteran newspaper The Washington Post. For him, the $250 million outlay was the equivalent of a large lunch, but six years on the move still has analysts scratching their heads.

At Amazon, innovation is practically a religion, and new divisions cracking new markets are regularly formed and funded. There's Amazon Shipping - a recent delivery service that had FedEx share prices tumbling - and the much vaunted Amazon Prime, which can claim an active account in roughly 50 per cent of all US households.

Perhaps most of all, there's Amazon Web Services (AWS), which today draws more revenue by itself than Amazon's entire e-commerce department. AWS hosts roughly a third of the world's cloud services, including commercial rivals like Netflix, and large swathes of the US government.

You don't get as big as Amazon without making a few enemies, and as public scrutiny of tech giants has intensified, Amazon has endured a steady stream of criticism. In 2015, it weathered its worst PR to date after an investigation by the New York Times alleged a "bruising" corporate culture, with "unreasonably high" expectations that left workers regularly sobbing at their desks. Company spokespeople excoriated the article's conclusions and methods, while Bezos said the piece "doesn't describe the Amazon I know".

There's also Amazon's tax payments, or to be more precise, lack of. The company made headlines last year for reportedly logging a grand total of $0 US federal taxes, despite posting $11.2 billion in pre-tax profits. The company indignantly maintains it pays every penny that's due.

Then there's Bezos himself, and his perceived unwillingness to engage in the usual lashings of billionaire philanthropy. His name is notably absent from The Giving Pledge - a commitment by many of the world's most wealthy to give away half their fortune before they die. Set up by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, signatories include Mark Zuckerberg and, intriguingly, MacKenzie Bezos.

These perceived iniquities have all garnered plenty of pushback, but recent protests have taken a more political tone. Amazon Web Services hosts Homeland Security databases that allow the government to track and apprehend migrants - an enormously controversial issue in Trump's America.

Attempts have been made to boycott Amazon, and they've been as effective as trying to turn back the tide.

Amazon is not currently facing imminent decline, but as and when that day comes, Bezos may already have moved on from the terrestrial realm. His passion project, Blue Origin, is one of the big three private space firms - alongside Virgin Galactic and Elon Musk's SpaceX - and in recent weeks scientists have undertaken final tests for fully-fledged commercial space flight.

This may seem like a giant leap for mankind, but for Bezos it is merely a small step. "It is time for America to return to the Moon," he told a rapt audience earlier this year, "this time to stay."

One is reminded once again of his high school valedictory address, almost 40 years ago. "Space, the final frontier," he signed off. "Meet me there."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here