2019 is the International Year of the Salmon, and with Kielder Salmon Centre also marking its 40th anniversary, Sarah Millington examines the fish’s burgeoning fortunes in the region

HAD things turned out differently, Kielder might have been home to the world’s highest fish pass, standing at a colossal 174ft. The question was, would it be too high for the fish to scale? In the event, we never found out – the plan was scrapped and Kielder Salmon Centre was built instead.

Completed in 1978, with the first fish being introduced to the River Tyne the following year, the conservational hatchery was designed to mitigate the reservoir’s effects. While the water was much needed, particularly for Teesside’s burgeoning steel industry, flooding from the dam wiped out vital natural habitat.

“When they built Kielder, it cut about seven per cent of all the Tyne’s catchment area, but in terms of the North Tyne, where Kielder is situated, it’s thought that it covered about 45-50 per cent of all the salmon spawning and nursery habitat for juveniles,” explains hatchery manager Richard Bond. “It was decided to build a hatchery up here at the top end of the reservoir. They looked at the habitat and thought that area would naturally produce about 160,000 juvenile salmon each year, so, as part of a public inquiry, it was agreed that the hatchery would stock 160,000 salmon each year to compensate for that.”

In fact, the Salmon Centre stocks – or releases captivity-bred fish into the wild – significantly more than that. “Over the years, we’ve been involved in a number of restoration programmes,” says Richard. “We’ve stocked the River Trent, in Derbyshire, with salmon, and we’ve been stocking salmon for estuary mortality compensation in the Tyne. The estuary is very long, narrow and shallow and, during the summer, when the water temperatures are very high and the water levels are low, that can lead to very poor water exchange and adult salmon can die. In 2003, more than a thousand dead adults were recovered from the estuary.”

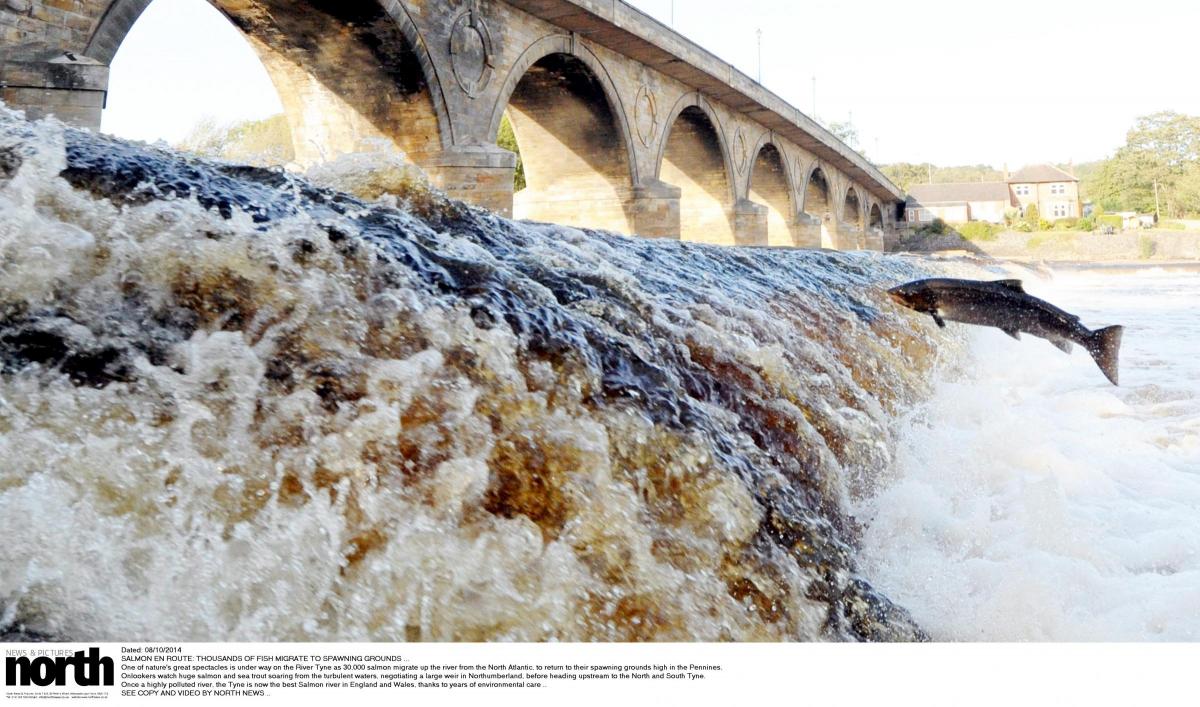

While still at risk from various factors, including climate change, the fortunes of salmon in the River Tyne have significantly improved. For a couple of years in the 1950s, not a single fish was caught by an angler – now the river is the best in England for the species by what Richard describes as “a significant margin”. The reason is mainly an improvement in water quality.

“The Environment Agency (which owns the Salmon Centre) and many other organisations have worked tirelessly over the past 40-50 years to improve the water quality in the Tyne estuary,” says Richard. “It’s probably better now than it has been in 100 years. The Environment Agency monitors it and we work with Northumbrian Water, which releases water from Kielder Reservoir. It doesn’t really improve the water quality, but it encourages those salmon that are in there to migrate from the estuary into the river, where the water quality is better. Without these water improvements, the salmon stocks would still be in the same state as they were back in the 1950s.”

But the Salmon Centre, which has a newly-refurbished visitor facility, isn’t just about salmon. In fact, Richard says he would consider breeding any at-risk aquatic species. “We’ve had a number of other projects running,” he says. “We reared Arctic char from Ennerdale, in the Lake District, to stop that population becoming extinct. Now we have our freshwater pearl mussels. They live to 100 or 110 years old and the River Tyne has the second largest population in England, but there are very few, if any, juveniles under 40 or 50 years old. They’re at the same level as snow leopards in terms of being endangered.”

As filter feeders, the mussels are a good indicator of water quality. No one really understands why they’ve stopped breeding – but the chances are it’s pollution-related. “It’s almost certainly water quality, but which part is hard to know,” says Richard. “It’s probably a number of factors. Microplastics is not something that’s really been studied in terms of freshwater mussels, but there is potential for them to take them into their stomachs. There’s ongoing research into that.”

The way they’re bred is fascinating – the eggs attach themselves to trout's gills, and the Salmon Centre catches the trout and keeps the mussels until they’re robust enough to be released. It’s early days, but the programme seems to be bearing fruit.

“We had a bit of a trial last year and were successful in producing some juveniles,” says Richard. “They’re likely to be the first ones bred in Northumberland for 50 years. We hope to release them back into the River Tyne next spring.”

Plans to mark the International Year of the Salmon are, as yet, vague, but, as the largest facility of its kind in England and Wales, Kielder Salmon Centre is sure play a part. For as long as there’s a reservoir, Richard says it will continue its vital work. “We’re in quite a unique situation in that we’ve got Kielder Water, which we need, so while the reservoir is there, we should be here as well.”

- W: visitkielder.com/visit/kielder-salmon-centre

- The Salmon Hatchery is open to the public until October 31.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel