Without Charlie Maddison, it is possible that Stan Hollis would not have made it back to tell his extraordinary story.

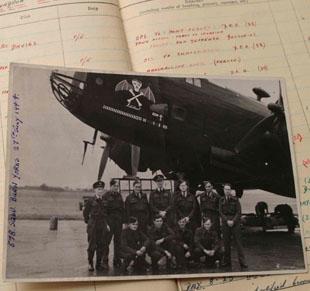

June 6, 1944, was just another morning to Charlie. He now lives in Willington, near Crook, County Durham, but back then was a flight engineer in the RAF, and at 2.35am was called to the briefing room. He was given details of what would be his 28th mission of the war aboard a Halifax bomber.

"At briefing we were told that we were to bomb a gun emplacement at Mont Fleury on the French coast, " recalls Charlie, who flew 37 missions during the Second World War and won the Distinguished Flying Medal. "That's all we were told. We weren't told that D-Day had started. We didn't know until we crossed the English Channel."

The journey from RAF Burn, near Selby, in North Yorkshire, took about an hour as the Halifax, accompanied by 19 others from 578 Squadron, doglegged down the country. It was getting on for 4am when they crossed the sea.

"It was a lovely bright morning, " he says. "We could see the Channel was full of ships and boats. You mention it and it was there.

We were amazed, flabbergasted, and the pilot just said: 'It's started'.

"We all felt proud that we were supporting those lads who couldn't really do anything for themselves in the landing craft and didn't know what they were going to encounter."

Charlie, now 82 and who spent most of peacetime underground in mines such as Brancepeth, Brandon, Dawdon and Easington, consults his handwritten log book.

"We were flying low at about 2,000ft, " he says. "We had to because there were fighter aircraft flying up and down the channel, and other bombers: 16,000 bombing raids were carried out in those 24 hours."

Because of their height, he remembers that there was plenty of anti-aircraft fire as they crossed the French coast, but this only helped them locate their target.

His logbook tells him that his plane dropped 20 500lb bombs on Mont Fleury battery and four cases of incendiary bombs (there were 12 incendiaries in a case).

Mont Fleury battery was the main German defence for Gold Beach. When Hollis' Green Howards came ashore there at 7.37am, the battery had received such a pounding from aerial and naval sources that it was no longer in service - but there was still withering fire from the pill boxes that Hollis cleared out so bravely.

A good half-an-hour before Hollis landed in Normandy, Charlie and his crew had landed back in North Yorkshire, and it was in the immediate debriefing session that they realised the cost of their mission.

Twenty Halifaxes had gone out, but only 19 had returned.

"One was shot down over the French coast, " says Charlie. "The Flight Engineer baled out and was brought back on a hospital ship."

The rest of the crew, though, were lost: possibly the first casualties of DDay.

"You just said 'there's another one gone', " he says.

"Of course, everybody was devastated, but it was a fact of war, and it did make a difference that we'd seen what was taking place in the Channel. We knew it was not in fun."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here