TEN years ago this week, Newcastle United faced an uproar from furious fans after Kevin Keegan announced his resignation as manager.

The atmosphere outside St James' Park grew increasingly tense as hundreds of fans vented their anger and a police cordon was prepared for tempers boiling over.

After a week of turmoil at the club, as many as 10,000 fans threatened to turn their backs on the club by boycotting the following home game against Hull City.

Fans blamed club owner Mike Ashley for the manner of Keegan’s departure after an ongoing row between the two over control of the club's transfer policy.

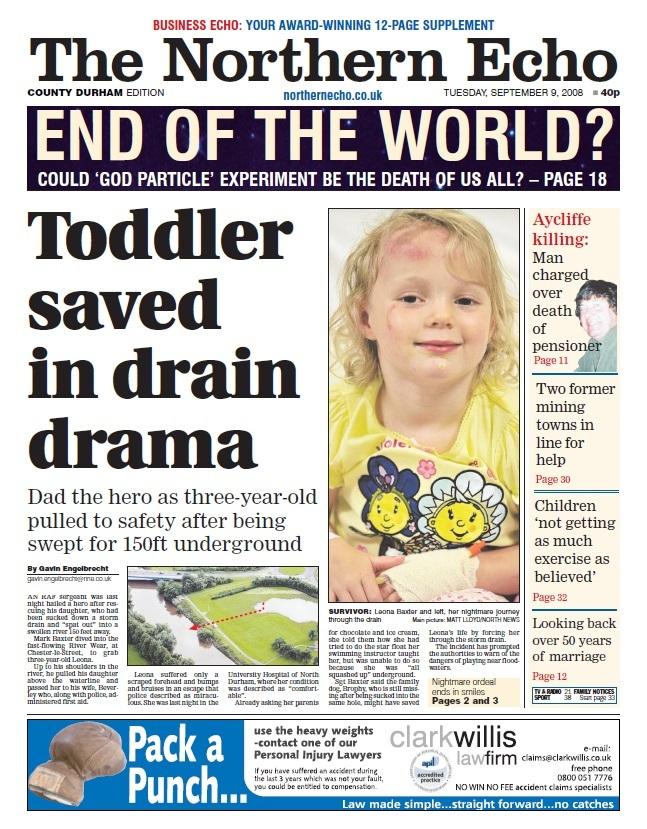

Also that week, an RAF sergeant was hailed a hero after rescuing his daughter, who had been sucked down a storm drain and "spat out" into a swollen river 150 feet away.

Mark Baxter, 34, dived into the fast-flowing River Wear, at Chester-le-Street, to grab his three-year-old daughter Leona.

Leona was happily splashing around in puddles caused by heavy rainfall when she fell down an open manhole cover and was swept away.

Mr Baxter went up to his shoulders in the river to pull his daughter above the waterline and passed her to his wife, Beverley.

Mrs Baxter said: "I just thought I had lost her. I kept saying 'we've got to get her'.”

Northumbrian Water spokesman Alistair Baker said the massive pressure to the water surface drainage system, caused by heavy rains, had forced the manhole cover to "pop off".

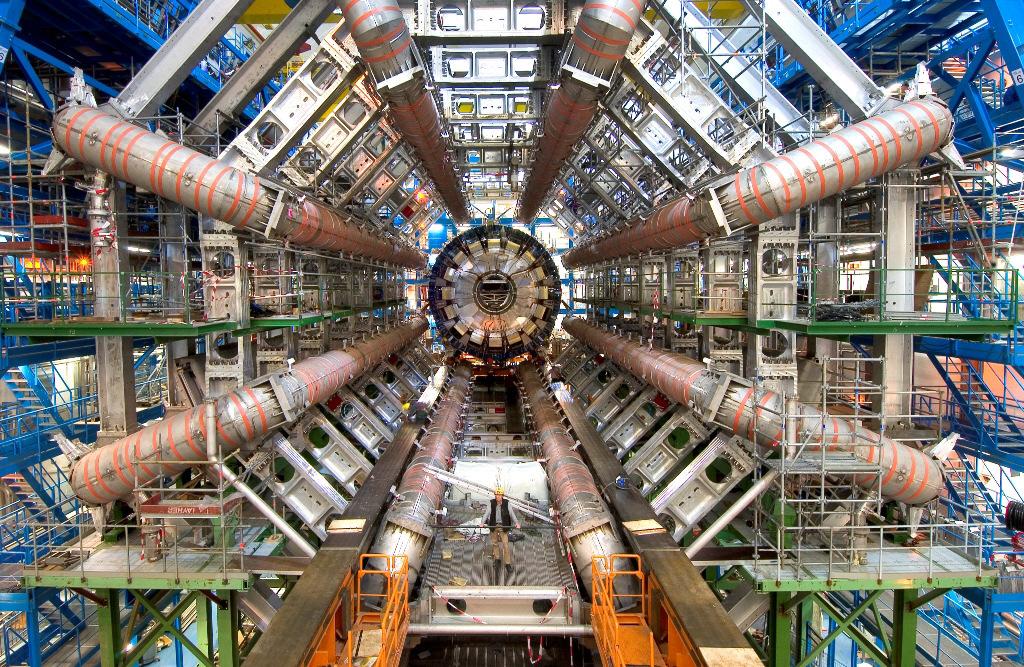

Meanwhile, scientists were divided as the countdown began to switch on a £4bn machine so powerful it could spell the end of the world.

Buried 300ft beneath the FrenchSwiss border, the Large Hadron Collider was designed to smash particles together at the speed of light in a re-creation of the Big Bang.

As its switch-on drew near, the scientific community awaited the first collision with anticipation - but some feared the worst.

Professor Otto Rossler, from the University of Tubingen, in Germany, believed the collider would create mini black-holes that could destroy the Earth within months.

However the European Nuclear Research Centre (CERN) conducted two safety investigations and concluded there was no significant risk posed by mini black-holes, insisting the world had nothing to fear.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here