BINKS, as everyone now knows, are the stone tables upon which milk churns were once placed. It’s a northern dialect word, and comes from “benc”, meaning bench.

But what, asks Phil Wilson, the former MP for Sedgefield, about Binks the surname, which is in his family tree.

Isabella and Henry Binks were his great-grandparents, and it must have been bricks which brought them together.

Henry was born in Durham in 1878, although his father, Robert, was originally from the Hipswell area just south of Richmond.

Binks as a surname seems to begin in Yorkshire, and it probably also comes from “benc” which was a Saxon word for an earth ridge – it may have been something that was heaped up to keep out the marauding Scots. The Binks could have been the family who lived in the shadow of the benc.

Robert Binks moved up from Yorkshire looking for work. His progress can be charted by the birthplaces of his children: Barningham, Winston and then Durham. Several of his sons became brickmakers. One, for instance, is listed as a “fire brick moulder”, and Henry himself was called a “brick setter”.

So it must have been bricks that cemented his relationship with Isabella, who was born in Waterhouses, near Durham, in 1877. Her father, George Parsons, was a brickmaker from Wiltshire; two of her brothers are listed as brickmakers, and Phil has a remarkable picture of her at work making bricks. She looks to be late teens, taking the freshly made bricks off a trolley with her bare hands, perhaps helped by her brothers.

The photograph has been trimmed to fit in a frame, but a bit of the photographers’ imprint can still be made out, showing that he had studios in “Durham & Darlington”.

The best guess is that this was taken when her family lived at Houghall, near Durham, where there was a colliery until the 1880s. Was there a brickworks near there?

But there were brickworks nearly everywhere, because as the Durham coalfield exploded in size, brickmakers were just as important as coalminers. Bricks were obviously needed in enormous quantities to build the new industrial premises – the 1,225 yard long Prince of Wales Tunnel that was built beneath Shildon in the early 1840s, for example, required seven million bricks; the 960 yard long Yarm Viaduct, built in the early 1850s, required 7.5m bricks.

But also, due to Durham’s geology, brickmaking was a natural by-product of coal winning.

Climate change about 280m years ago killed a forest that had been growing in the shallow Zechstein Sea. The trees fell to the seafloor and as it dried up, they were transformed into coal and the mud immediately beneath them turned to clay.

In fact, it became good quality clay – fireclay – and the bricks made from it could withstand high temperatures.

It was known locally as “seggar” and most layers of it produced traditional red bricks, in several places around Crook, it produced a creamy,

A local peculiarity was that while most layers of clay produced traditional red bricks, seggar in some places produced creamy, buff-coloured bricks. The main buildings in Darlington – Barclay’s bank, the town clock, market hall and many mansions - are made from this distinctive brick because the clay came out of the Peases’ mines up near Crook.

Most pits had their own ancillary brickworks, most of which pressed the name of the colliery, or its owner, into the bricks. Back in 2017, Memories visited Kenny Bowen in High Etherley who has hundreds of different Durham bricks built into walls around his garden. The tram waiting sheds at Beamish museum are also built of scores of named Durham bricks.

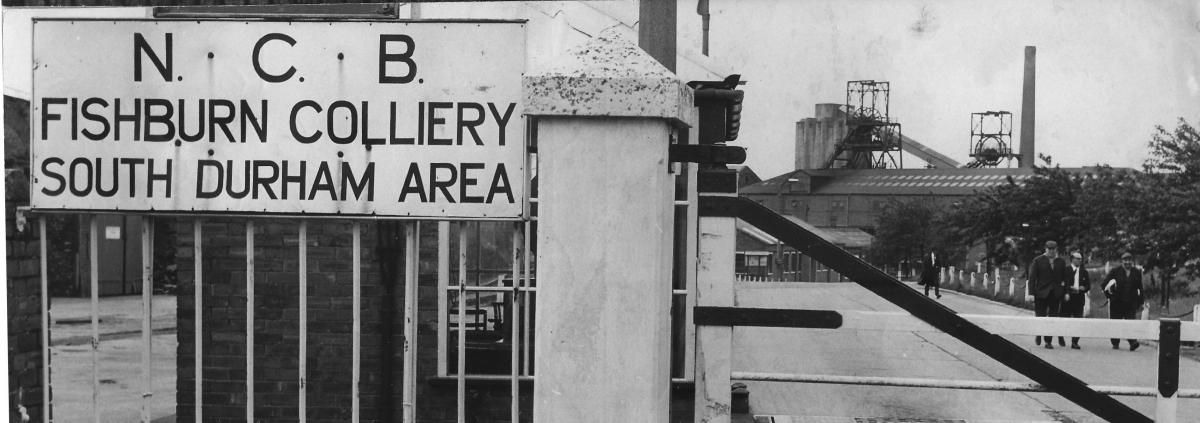

So the marriage between Henry Binks and Isabella Parsons, in 1898 at St Oswald’s Church in Durham, was one that was made in brickmaking heaven. They settled in the Fishburn area, where Phil’s grandmother was born in 1902, surrounded by collieries.

In 1910, Fishburn colliery was sunk, and Henry went to make bricks there.

Isabella had at least six children who survived to adulthood, and she died in 1934, aged 57. According to The Northern Echo of December 19, 1934, she had the honour of being the first burial in the new Fishburn cemetery – previously, people from Fishburn were interred in Sedgefield.

Sadly, she was joined only three years later by Henry, who is believed to have died after puncturing his lung in a pit accident.

- Do you have any Binks in your family tree, or any information about the family? Do you have any brickmakers? Can you help us with brickworks at Houghall or Fishburn? And do you have any unusual Durham bricks – we’d love to see them! If you can help, please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

FISHBURN was one of the last collieries to be opened in the Durham coalfield. It quickly grew into a huge concern, employing 1,522 at its peak in 1935, and its closure on November 30, 1973, meant the loss of more than 600 jobs.

However, the neighbouring cokeworks lasted until the mid-1980s, employing more than 250 people.

Collieries and cokeworks – and, indeed, brickworks – went hand-in-hand, with the Fishburn cokeworks using 365,000 tons of "washed smalls" a year – not underwear, but prepared pieces of coal delivered direct from the pit by a conveyor belt.

Although the pit was only open for 63 years, 74 men lost their lives working there, the last being loaderman JA Charlton, who was killed on May 21, 1970.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here