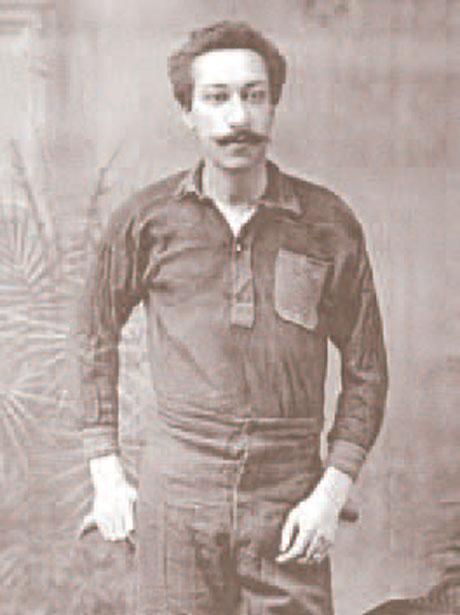

ARTHUR WHARTON was the fastest man in the world. He was the greatest goalkeeper in the country. He was lionised by fans who loved his athleticism and his showmanship, and, wherever he went, he was big box office.

He was also black – the first professional black footballer in the country – and so The Northern Echo fondly called him “Darkey”. The Darlington and Stockton Times referred to him as the “coloured Colonial” and “a brunette of pronounced complexion”

whereas other newspapers termed him “the dusky flyer”.

Times have changed. For the better.

Possibly because Arthur was black, once his sporting powers waned, he was allowed to fade away into a sad decline of alcoholism and penury until he was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in South Yorkshire in 1930.

Now a campaign is beginning in Darlington, the town which discovered him, to have a statue erected in his honour.

Despite Arthur’s sad demise, he’d been born practically into royalty. He came into this world in 1865 in Accra, the capital of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in West Africa.

His mother, Annie, was related, through her mother, to the Fante royal family, although her father was a well-to-do Scottish trader. Arthur’s father, Henry, was born on Grenada in the West Indies, although he too had Scottish genes.

His father was a wealthy sea captain from Glasgow and his mother was an African who had ended up in the West Indies due to the slavery of her ancestors.

Henry was sent to Glasgow for his education, and then went as a Methodist missionary to the Gold Coast. There he met Annie, and together they had ten children, one of whom was Arthur.

Henry wanted a British religious education for Arthur, and at the age of 17 the youth was sent to a Methodist school at Cannock, in Staffordshire. When that closed, in 1884, he transferred to Cleveland College, in Darlington.

In May 1885, he entered the Darlington Cricket Club sports day at Feethams.

“He was then quite unknown,”

said The Northern Echo in a 1913 interview. “He was given a few yards start. Most people thought the was running in his bare feet because of the brown pumps he wore…‘blending’ with the colour of his skin. Darkey kept the lead all the way, but his ignorance in the rules almost proved his downfall.

For when he reached the tape, instead of breaking it he ducked underneath, but Tom Mountford who was second and who could have claimed the race, like a true sportsman, refused to take advantage. Thus Darkey won his first race.”

Suddenly, he was a star – with a superstar’s attitude. The following month, he won a race in Middlesbrough by three yards, but when the organisers handed him the second prize of a salad bowl, he angrily smashed it on the floor and colourfully advised them to make a new one out of the bits.

Arthur had a peculiar running style. The Darlington and Stock-ton Times said: “He has neither system nor style, but he runs like an express engine with full steam on from first to last, with a result that makes both system and style unnecessary.”

The Northern Echo in 1913 went further: “When running, Darky (sic) always wore long, bulky trousers which were suspended by elastic and not buttoned in the usual way. His style of getting over the ground – if it could be called a style – was very ugly.”

At the end of the 1885 summer running season, Arthur joined Darlington FC – as a goalkeeper.

He played about 20 games for the newly-formed club in 1885-6 and was selected for county teams as far north as Northumberland.

In those days, the goalkeeper could legally be barged and booted into the net – some teams specifically appointed a “rusher”

to assault the keeper. Arthur’s speed assisted him in escaping trouble, and his athleticism assisted him in avoiding it – he would crouch at the foot of the post, away from the flying boots, and at the last moment leap to clutch the ball.

“He earned fame as a brilliant goalkeeper,” said the Echo in 1913. “He could fist a ball almost as far as a man could kick it.” He could also swing from the crossbar and catch the ball between his legs.

In July 1886, Arthur entered the Amateur Athletics Association championships at Stamford Bridge in the name of Darlington Cricket Club. He astounded the 2,000 crowd by winning both his 100-yard heat and the final in ten seconds dead – the first time anywhere in the world this had been reliably recorded.

Wherever he went, he was big box office. For the new football season, he signed to play in the FA Cup (the only national competition) as an amateur (collecting sizeable expenses) for Preston North End (then one of the biggest clubs in the country).

They reached the semi-final where they lost 3-1 to West Bromwich Albion – Wharton, though, was described as “blameless”.

As well as county and charity matches, Arthur turned out for the Quakers. In the third round of the Durham Cup, they beat Brankin Moor (presumably a Darlington team based near where the stadium is today) 3-0 with Arthur playing outfield and scoring two goals.

In the semi-final against Darlington St Augustine’s (the biggest team in town), he was back between the sticks. A crowd of 6,000 men (men paid and were counted; women got in free and were not) travelled on special excursion trains to see the game in Middlesbrough. Arthur was “impassable… miraculous” as his team won 4-1.

The final was against Sunderland.

The referee was a “Mr Bastard of Middlesbrough”. But Arthur was absent. It was said that he was suddenly ill, possibly with scarlet fever – an exotic illness for an exotic fellow, but the truth might have been more prosaic: drink. Darlo lost 1-0.

In the summer of 1887, he held his AAA title in a commendable 10.2 seconds, and he cycled from Blackburn to Preston in a record two hours – he would have been

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here