Darlington Borough Council is spending nearly £4m of National Lottery money to restore South Park. Echo Memories begins a series on the park by looking at how it became the first of its kind in the North-East

THE story of one of Darlington’s finest leisure facilities begins, strangely, in Hartlepool. Because, in the 17th Century, in Owton, which is now one of Hartlepool’s less salubrious council estates, lived James Bellasses.

His family came from France with William the Conqueror in 1066. The family name came from a corruption of their motto “Bon et bel assez” (Good and beautiful enough).

The “Bel-assez” settled at Cowpen Bewley, near Billingham, and tried many ways of spelling their surname.

In the 12th Century, John of Bellasis wanted to go on crusade to the Holy Land, but found his huge estate required too much looking after to allow him to leave. So he agreed with the church in Durham to swap it for the working village of Henknowle, near Bishop Auckland, which could look after itself in his absence.

When John returned from his crusade he wanted his green and pleasant land near Billingham back, but the church refused to undo the deal. A stained glass window in St Andrew’s Church, in South Church, near Bishop Auckland, bore testament to John’s stupidity. It contained his coat of arms and the rhyme: “Bellysys, Bellysys, daft was thy sowell When thee exchanged Bellysys for Henknowell.”

After this setback, the Belasseses married well and soon regained their position as one of County Durham’s leading families.

One of their number was Sir Henry Belasses, MP for Grimsby, who died while under the befuddling influence of alcohol during a duel with his drinking buddy.

Lady Susan Bellasis became one of King James II’s mistresses, knocking around with another of the king’s lovers, Catherine Sedley, the Baroness of Darlington.

Thomas Bellasses, the second Baron Fauconberg of Yarm, married Oliver Cromwell’s daughter.

Sir Richard Bellasyse of Ludworth and Owton, MP for the City of Durham from 1701 to 1717, was buried in Westminster Abbey.

And Elizabeth Bellasses, despite being married to the Duke of Norfolk, eloped with Lord Lucan, by whom she had a son. He also went by the title of Lord Lucan and it was he, with Bellasses blood coursing through his veins, who sent the Light Brigade charging down the wrong valley during the Crimean War.

One of this noble family’s lesser lights was James Bellasses of Owton – although he, too, clearly had his moments, because in September 1633 he was fined £200 by the High Court in Durham for improperly marrying Isabel Chaytor.

On October 10, 1636, James made his will ready for his death in 1640. He left five shillings each to 20 men and 20 women “to helpe carry me to the church and buriall”.

He was buried in Stranton Church, near Hartlepool, and at one time had a marble monument over his grave that showed his body rising from his tomb. The monument disappeared when the church was refurbished in the 1850s.

James left 40 shillings for the poor of Blackwell, on the outskirts of Darlington, 40 shillings to repair the highway from Whitland Gate into Darlington, and 40 shillings to repair the highway between Haughton-le-Skerne and Darlington.

He also left a cottage on the corner of Skinnergate and Blackwellgate for poor linen and woollen workers, plus sufficient timber, bricks and stone to build a small factory for them beside the cottage.

Unfortunately, the idea never really worked, and the property was turned into three almshouses for poor widows.

The almshouses were demolished in 1898 and the Bainbridge Barker store built on the site (a motorists’ shop with a gym above it stands on the corner today).

When the almshouses were demolished, the large stone lintel was removed to 164 Yarm Road, where it was last heard of in 1960. If it is still there, it will be hard to miss, because carved on it are the words: “Almshouses left by James Bellasses Esq, 1636.”

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of James’ will was that he bequeathed “four beast gates on Bracken Moor” to the town of Darlington. These beast gates, or fields, were to be administered by trustees who would rent them out to farmers.

In 1652, one of James’ descendants, Lord Fauconberg of Yarm, greedily demanded that he should receive the rent, but the trustees stood firm and gave the money to povertystricken linen and woollen workers.

These fields made up a thin plot of nearly 20 acres beside the meandering Skerne, off Grange Road. The plot was known as “Howdens” – or “Poor Howdens” because of its charitable status.

The charity worked well for two centuries until Darlington started to change. In the 19th Century, linen work died out as industrial workers moved in.

They lived in tight terraced houses and grubby alleyways with no sewers, no fresh water and no rubbish collections.

Overcrowding was common, with humans living cheek by jowl with animals. Houses were next to belching factories, which were next to bloodstained slaughterhouses.

Disease was rife. Death was a regular visitor.

To address these problems, Darlington changed the way it governed itself. Previously, an unelected board of commissioners had run the town, but it had been so unsuccessful that ten per cent of ratepayers used the 1848 Public Health Act to demand the Government set up a board of health.

On September 27, 1850, 74 ratepayers stood as candidates in the elections to choose the 18 members of the new board.

What happened to Poor Howdens was a product of these changes. The trustees needed a way to channel the charity away from the few remaining linen workers to the new industrial underclass.

The commissioners needed to save their skins by showing how dynamic they were. They entered into negotiations with the trustees to set up “a Park or Pleasure Ground” on Poor Howdens, “for the free daily use of all classes of society”.

The board of health took up the project with alacrity to show how much better it was than the commissioners – although the board, the commission and the trustees were, by and large, the same powerful people.

But there was much merit in the scheme. William Ranger, a doctor, said in 1850: “There are no places for exercise or recreation for the inhabitants, many of whom are pent up in confined courts.

“The importance of providing for those engaged in manufacturing the means of rational amusement has now been recognised, and the setting apart of places for the above purpose forms properly a part of the sanitary measures for every town.”

Indeed, Sheffield (1841) and Liverpool (1842) had formed the first municipal parks in the North. But Darlington can lay claim to having the first in the North-East, ahead of Sunderland (1857), Gateshead (1861), Middlesbrough (1865) and Newcastle (1873).

Public meetings were held, and the town agreed that the board of health should lease the fields from the trustees of Poor Howdens for 21 years at £32 per annum.

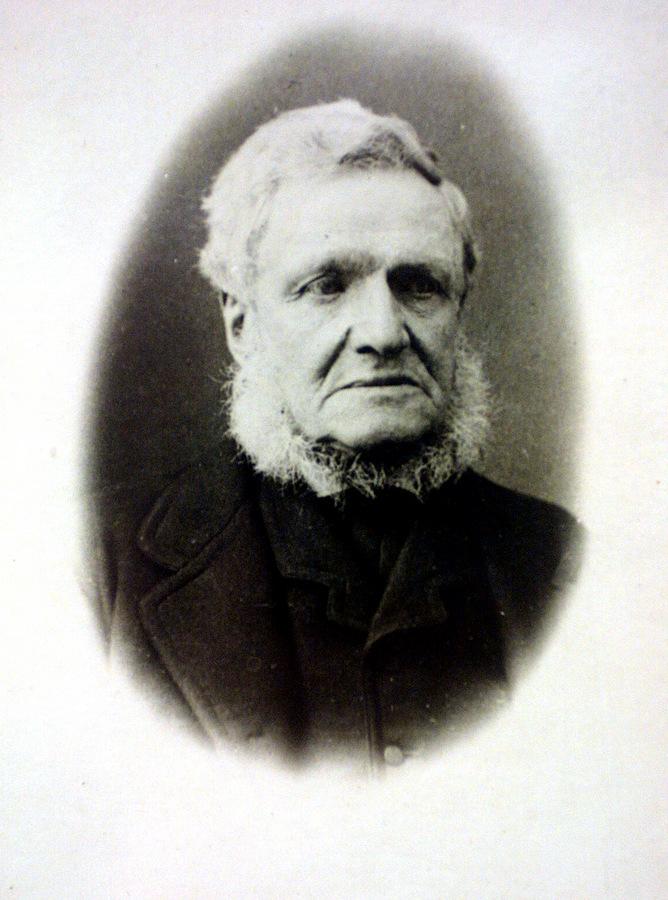

In 1851, the board set up a committee to oversee the creation of what we today know as South Park. Its members were: Joseph Stephenson (1800 to 1883) – An uneducated relative of railway pioneer George Stephenson. He started as a platelayer on the Stockton and Darlington Railway before it opened, but became one of the foremost railway surveyors of his generation.

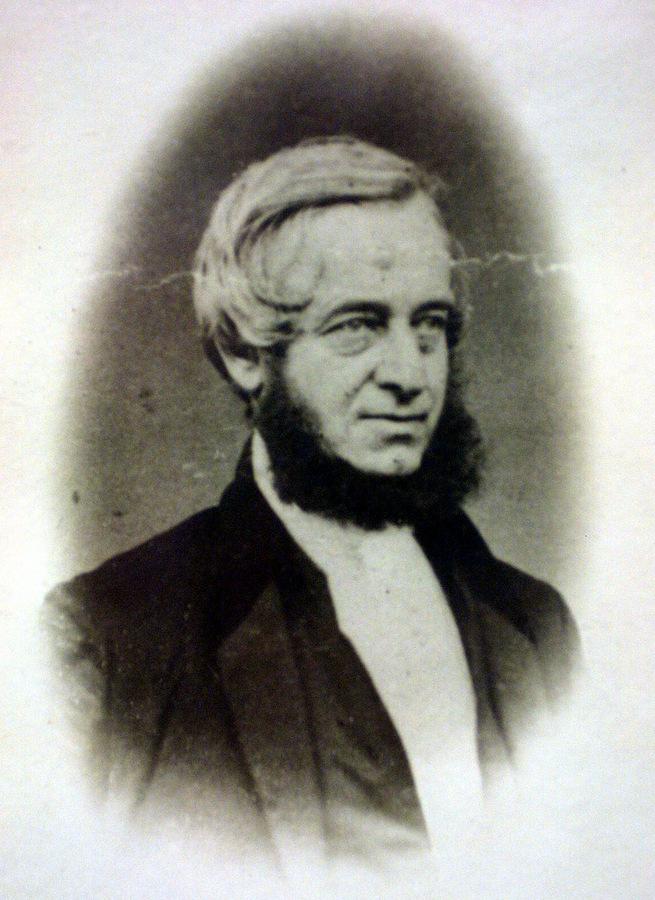

John Harris (1812 to 1869) – A penniless Lancastrian Quaker when he arrived in Darlington in 1835, he became one of the foremost railway engineers of his generation. He ran a foundry in Albert Hill, and lived in the Woodside mansion almost opposite South Park.

In 1851, he built the Freeholders’ Estate, off Yarm Road, where the properties were big enough for the owners to qualify for a vote (he hoped they would follow his example and vote Liberal). A street on the estate is named after him.

William Backhouse Junior (1807 to 1869) – A banker who, with his father, William (1779 to 1844), helped to create herbaceous borders and alpine rockeries at their mansion, Elmfield (now the KFC takeaway, in High Northgate).

Elmfield’s grounds make up most of North Lodge Park.

John Church Backhouse (1811 to 1858) – Another banker, who married into the Gurney family of Norfolk bankers. His baby daughter and his wife died in 1848. He then died, aged 47, leaving a 14-year-old orphan whom his sister, Eliza Barclay, of Blackwell Hill, adopted.

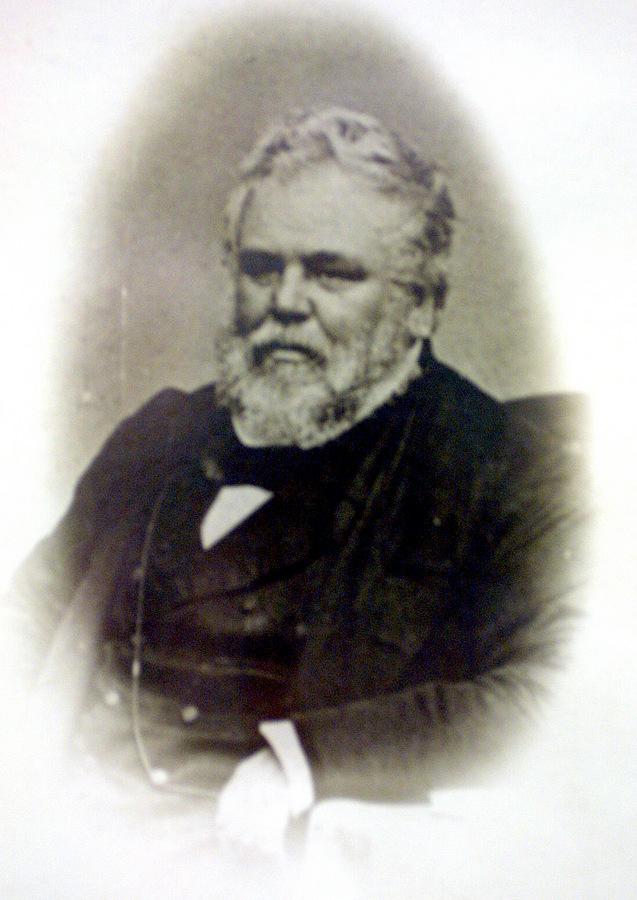

Robert Thompson (died 1884) – The black sheep of the committee. With his brother William, Robert was Darlington’s leading stockbroker and proprietor of the Darlington and Stockton Times.

The Thompsons were passionate advocates of the park, but could not have foreseen how their business catastrophe would make it such a valuable asset.

That catastrophe is a story for another week. But as Robert and his fellow committee members set about creating the park, it will come as no surprise that his newspaper, the D&S Times enthused about it: “Nothing is more calculated to benefit those who during the live-long day are confined to the crowded workshop, or the close habitations which abound in our towns, as to provide for them a place of recreation – away from the smoke and nuisances and pestiferous influences which in the best regulated towns undeniably exist – out in the country, amidst the pure air, where old and young, the man and the child, can ramble at freedom over several acres of land, surrounded by no influences but those of beautiful scenery and picturesque landscape, and under no fear of being ‘had up’ for trespass,” it said.

“We congratulate our fellow townsmen upon this most important adjunct to our town.

It will become one of the lungs of the place, and will, we trust, prove a great and lasting benefit to its inhabitants.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here