A weathered stone and an enthusiastic mason all at sixes and nines - both the ingredients needed for a blunder that has survived more than a century.

A literal is a common mistake in something as common as a newspaper: a slip of the fingres and two letters are accidentally switched around. Such is the ephemeral nature of newspapers that the literal is consigned to the recycling bag before the day is out, and the embarrassment is forgotten.

NOT so the stonemason.

If his chisel perpetrates a literal, it is carved in stone for all to see, in perpetuity.

As it is in Barnard Castle, which may well be home to the North-East’s most monumental mistake.

For more than a century, the date stone on the County Bridge has said 1596. Yet the stonemason should really have carved 1569, the date the bridge was rebuilt following a famous uprising.

Man has crossed the Tees near the bridge for millennia, certainly since the Romans marched this way from Lavatrae (Bowes) to Binchester (Vinovium).

They used a ford – the village of Startforth on the Yorkshire bank takes its name from the “street ford” – which was a little to the north of the current crossing.

Being Romans, they didn’t bother with today’s meandering along Bridgegate, up The Bank and through the Market Place. They yomped straight over the river, up the bank, and, without deviating, went out along Galgate. In the Romans’ day, there wasn’t much to cause them to stop in Barnard Castle – there was no castle, and no Barnard. Indeed, Barnard Castle is a new town: it only grew up after Bernard de Baliol had built a castle there in the early part of the 12th Century.

Bernard’s family had been placed in charge of much of the North by William the Conqueror, and Bernard’s castle was at the southern gateway to his territory. He built it on the rocks 80ft above the Roman ford so he could keep a watchful eye on who was crossing.

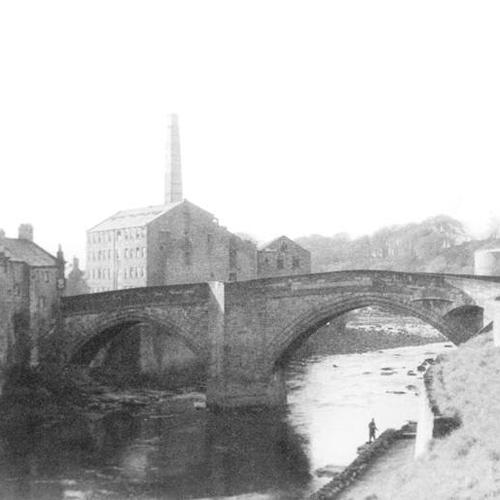

Man doesn’t like getting his feet wet, though, and so in the 14th Century, a bridge was built. Sixteenth Century travel writer John Leland described it as “the right fair bridge on the Tese of three arches”.

Attached to the town by a new street called Bridgegate, it made Barney a trading centre.

The big drama, though, was played out in 1569: the Rising of the North. Queen Elizabeth I decreed that England was Protestant, but the Catholic families of the North-East, led by Charles Neville, the Earl of Westmoreland, who lived in Raby Castle, disagreed, and a plot was hatched to overthrow the Queen.

Sir George Bowes, of Streatlam Castle – between Barney and Staindrop – was loyal to Elizabeth and, worried by the bellicose antics of his neighbour, in November, holed himself up in the stronghold of Barnard Castle.

Westmoreland captured Streatlam and then, on December 2, surrounded Barnard Castle with 5,000 men. Sir George was stuck inside, armed with only four slings and one cast iron cannon.

Westmoreland held all the advantages: more men, superior weaponry, freedom, food and water. He just had to sit and wait for Sir George to starve to death.

Westmoreland’s men taunted Sir George with a playground rhyme that must have inspired Monty Python:

A coward, a coward of Barney Castle

Daren’t come out to fight a battle.

Sir George’s men couldn’t take this taunting. He wrote: “In one daye and nyght, 226 men leapyd over the walles, and opened the gaytes, and went to the enemy; off which nomber, 35 broke their necks, legges or arms in the leaping.”

The defectors told the enemy of the secret underground water supplies that were keeping Sir George sustained within the castle. The supplies were cut, and on December 14, Sir George surrendered.

But because he was a good egg, Westmoreland didn’t kill him. He allowed him to walk free, no doubt taunting him some more as he went.

During the course of the siege, the Queen’s commander, the Earl of Sussex, had arrived at Croft Bridge, near Darlington, with an army of 20,000. Sir George joined up with him, and when Westmoreland’s men heard about the enormity of the force facing them, they ceased their taunting and melted away into the Teesdale countryside, where they pretended they hadn’t been up to anything naughty, certainly not any besieging.

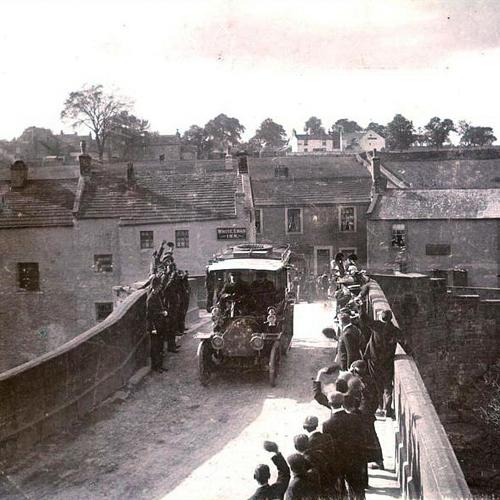

The Rising of the North was over. The Queen was still on her throne. But the County Bridge had been so damaged during the siege that it had to be rebuilt, its three arches being replaced by two which seem to spring out of the riverside rocks.

A stonemason carved the date 1569 on a stone in the refuge in the centre of the bridge. Other stones in the refuge noted the county boundary between Durham and the North Riding of Yorkshire, which gave the bridge its name.

It was also the boundary between the dioceses of Chester and Durham. A building that remained in the centre of the bridge until the start of the 19th Century may even have been a chapel, which gives rise to the story of Cuthbert Hilton.

Cuthbert was the son of the Reverend Alexander Hilton, who was curate of Denton in 1681. He studied theology under his father, but was no more than a Bible clerk, yet he occupied the chapel and, on payment of half-a-crown, he would lay his broom along the boundary across the bridge.

A couple who needed to marry in a hurry would jump over the broom and as they were in mid-air – when they were neither in the territory of the Bishop of Durham nor that of Chester – Cuthbert would pronounce them man and wife. They went on to live together “over the brush”.

The climate in those days must have been very different.

In 1740, the river at the bridge froze so solidly that horse races were held on the ice.

Tents were pitched on the Teesdale tundra, and braziers warmed the racegoers.

On November 15, 1771, the greatest flood overwhelmed the district – riverside communities from Tyne to Swale were inundated. At Barney, the river rose above the southern arch, sweeping away the stonework so the cobbler who lived in the “chapel” in the centre had to lay a ladder over the void to reach Yorkshire.

As the flood swept through, a weaver in the buildings attached to the bridge on the Startforth side abandoned his apparatus in his lower rooms and fled to his attic.

As the waters retreated, he retrieved the textile that he had left in his dye-kettle. The London buyers were astounded by its vibrancy and placed repeat orders, but the weaver “not being assisted by the genius of the river, failed in every attempt” to replicate the colours.

After the 1771 flood, the County Bridge was restored and was strengthened at the Durham end by “squinch”

arches. This sounds like a word a stonemason might make up, but a squinch or a scuncheon is a diagonal support.

While the scuncheons were being squinched, the date stone in the central refuge was weathering away until, by the end of the 19th Century, it was barely legible. A mason thought it was worth preserving for posterity and as he was carving a stone for a new wall on the Durham side, he thought he’d chisel in the old date.

A slip, though, of either fingers or memory and the last two digits were transposed.

He’d created a literal which is, quite literally, an indelible howler.

With many thanks to Barnard Castle historian Alan Wilkinson, to Gordon Dolby for help with the pictures, and to the reader who many months ago requested an article on the County Bridge. For more on Teesdale and the Rising of the North, see the Echo Memories blog on the Echo’s website.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here