From a distinctive landlord to grounded warplanes, and everything in between.

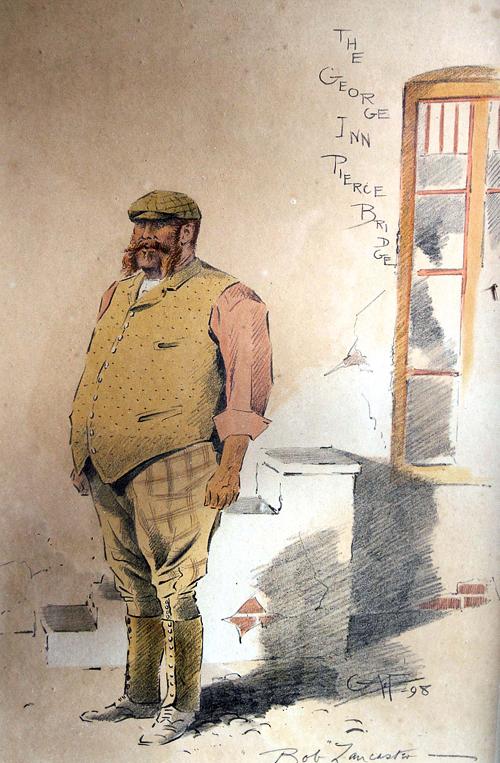

ROBERT LANCASTER was a large man who was larger than life. You can see him on today’s front cover, his large frame filling the photographer’s frame outside the George Inn, in Piercebridge, where he was landlord for nearly 30 years.

Even his dogs are staring in awe of him.

“The apparel marked the man,” said his obituary in the Darlington & Stockton Times (D&ST) in 1917 and, appropriately, his greatgrandson, George Graham, still has a large colour lithograph, which shows him wearing a distinctive country suit.

His obituary said: “His large check suits and leggings always marked him as a sporting and original character, and in his nature few men were more cheery or more full of anecdote.”

Robert came from Harome, near Helmsley, and was steeped in horses. He boasted that he had attended every horse fair between Land’s End and John O’Groats, he regularly won prizes at the Royal Hackney Show and he had such a good eye that he made several purchases on behalf of the king of the Belgians, Leopold II.

In the 1850s, he emigrated to the US and rode from New York to San Francisco on horseback, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he came home.

He became brewer at the Turk’s Head, in Darlington’s Bondgate, before taking charge of the stables at the King’s Head Hotel, for ten years. Then he got his own pub: first the Spotted Dog in High Coniscliffe and then, the George (which, because it is south of the Tees and in Yorkshire, is really in Cliffe and not Piercebridge).

Under him, the George became a centre of the horse and hunting community.

“The house was seldom passed without a call by either a master of hounds, a huntsman, rider or driver, or any pedestrian tramping along the old Roman road,” said the D&ST.

Several members of royalty stayed with him, including Prince Albert Victor, who, as Queen Victoria’s eldest grandson, everyone assumed would one day be king. However, a week after his 28th birthday and six weeks before he was due to be married, he caught influenza at the tail end of one of the 19th Century’s great pandemics, and died.

His intended, Princess Mary of Teck, laid her bridal wreath on his coffin, and then fell in love with his oldest brother, Prince George. When he became King George V in 1911, she became his Queen Mary.

Back at the George, big Robert Lancaster retired in 1907 to Hackney Cottage, in High Coniscliffe, where he died ten years later. That the drawing of him is by George Algernon Fothergill shows that he really was a large noise in hunting circles because “GAF” only chose the big names as his subjects.

• Robert Lancaster’s full obituary is on the Echo Memories’ blog on The Northern Echo’s website.

GROUNDED warplanes obviously had a memorable effect on the children who were taken to see them.

Some were put on display to raise money for the war effort, and youngsters were allowed to sit in the cockpit and play with the controls if their parents paid a few pennies.

Others, of course, were victims of the conflict that fell from the skies.

Last week, K Jennison, from High Etherley, asked about a plane that his mother took him to see after it had crashed near the railway line in Shildon.

Vincent Horan remembers the accident happened at about 5pm on May 31, 1944. A short-nosed Stirling bomber on a training flight from Lincolnshire caught fire and crashed onto the Cooperative farm, killing the entire crew.

“I was only five, but my brother was an office boy at the railway works and he saw it circling overhead before it crashed,” says Vincent, who now lives only 400 yards from the crash site.

“We ran over Dabble Duck – it was then a fur factory – and when we got there, there was quite a crowd. I remember these two ladies and they said ‘they are carrying the bodies out in bags’.”

The pilot was 27-year-old Pilot Officer Stanley Raymond Wilson, who left his parents and his wife, Marguerita, in Newcastle, where he is buried, although the rest of the crew were Canadians.

Post-war, the Jubilee Estate was built on the farm’s fields. It is said that the Canada link caused one of the streets to be named Maple Avenue, although practically all the estate is named after trees – magnolia, jasmine, fir, pine tree, larch, lime etc – so perhaps it is coincidence.

Vincent Horan’s records also show that on February 26, 1939, two biplanes crashed in a field in New Shildon. The Northern Echo carried a report the following day, saying that engine trouble had forced a reconnaissance aeroplane from 607 Squadron at RAF Usworth, near Sunderland, to land undamaged in the field at 11am.

“An hour later, an Avro from the same squadron, newly delivered only a week ago, came over and made a perfect landing in the same field in order to investigate,” said the paper. “Later, in taking off, it crashed through a hedge and completely overturned.”

Shildon LNER ambulance class was practising nearby and rushed over to administer to the two shocked and cut airmen, who were taken to a farmhouse to recover. The aeroplane was very badly damaged and the propeller broken off,” said the Echo.

Not a good start to a war.

TALKING of Scruton, as we were on the previous page, the original Scruton manor mill and farmhouse was near the end of the RAF Leeming runway. They were destroyed on March 13, 1944, when a Whitley bomber of 77 Squadron crashed into them.

All the crew were killed.

THIS was all started by Darrell Nixon’s request in Memories No 14 for information about a plane his grandfather remembered crashing in June 1941 near Page Bank, Spennymoor.

Harry Spence, in Tudhoe Colliery, has records which show that on June 4, 1941, a Sea Hurricane fighter – number V7665 – again from RAF Usworth was on an altitude training exercise when an engine failed. The pilot, VS Neil, attemped a crash landing. He ploughed through a hedge near Page Bank and survived.

However, he got a mauling at the subsequent inquiry, which concluded: “The pilot was aware of being south of (aero)drome. No excuse for being out of range of R/T (radio contact). Disciplinary action taken as aircraft could have been flown back to drome.”

DARLINGTON’S North Park, which featured in Memories No 25, has been a major part of life for several generations of the Johnson family. “I’m sure my father and his brothers and sisters, who were born in the early 1900s, would have enjoyed the space away from their crowded little house on Whessoe Road,” writes Colin Johnson, who admits to spending too much time on the swings, roundabouts, bowling green and tennis courts when he should have been swotting for exams.

“My memories are from the Forties and Fifties,” he says, “I wonder how many people will remember the excitement of the coming of the big circuses, Bertram Mills and Chipperfield’s, just after the Second World War?”

DEREK WILSON in Spennymoor adds to the spate of icerelated tragedies that have featured here recently. He remembers a similar incident on Chucky Dodd’s pond near the old greyhound stadium in Merrington Lane, Low Spennymoor, in the early Fifties.

Two boys, the Hutchinson twins, perished one school dinnertime, one falling through the ice and the other dying trying to help him out. It is very tragic, but old colliery ponds were just part of the scene at the time in the history of the Durham coalfield,” says Derek.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here