How the extraordinary vision of a railway pioneer turned a smugglers’ hideaway into one of the region's most cherished seaside resorts.

Exactly 150 years ago, a small group of men with spades huddled together by the sea. They had come not to build a sandcastle, but to create a tourist resort which still tugs at the hearts of all who visit. From the men’s vantage point, a vast spread of beach stretched out towards a gaggle of tumbledown fisher-cottages beneath a huge, sheer cliff that reared up to the sky.

WE can only guess if that January day were cuttingly cold, the sea and the sky painted in chill greys, or if it were sparklingly clear, the brilliant blue up above contrasting brightly with the wide expanse of the golden beach.

But the men made a start in a turnip-field on a clifftop.

“There were not more than a dozen persons present, including our reporter and the bricklayers and bricklayers’ ‘paddies’,” said the Darlington & Stockton Times.

“After spreading the mortar, which Henry Pease did in a real workmanlike manner – none of your silvertrowel style – he lowered the stone, from eight to ten stones in weight, by his own muscular strength, without any mechanical assistance in the shape of rope and pulley.”

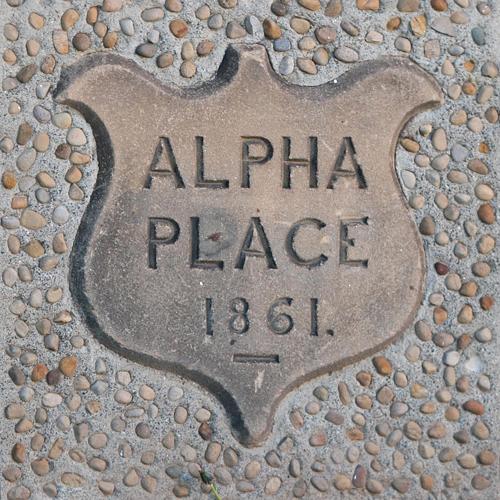

And so, on January 23, 1861, the first street, named Alpha Place, of the new railway town of Saltburn was begun. The stone that Henry laid can still be seen, only now built into modern flats.

“A few houses – about half a dozen – are being built within a score yards of where the station will be erected,” said the D&S Times. “They are the first buildings commenced.

“Mr Pease went down to lay the foundation stone of these houses in reality, but of a large busy place in imagination.”

Mr Pease’s life was not the first in which these cliffs loomed large. Directly opposite where he was digging was the massive outline of Huntcliff with a dollop on top of it: Warsett Hill. On Warsett Hill, Bronze Age man built nine tumuli in which to bury his dead, and on the edge of Huntcliff the Romans built a signalling station in about 360AD.

It was a wooden tower surrounded by a sturdy wall and a ditch, its inhabitants looking to sea for barbarian pirates raiding from the continent.

Should they have spotted a sail, they would have lit their beacon and signalled – flame by night and smoke by day – down the coast to Goldsborough, near Whitby, and inland to Catterick and Piercebridge.

In about 390AD, as Roman rule was breaking down, the station was overrun and its signallers were murdered.

Their bodies were thrown down a well where, even though their station had tumbled over Huntcliff, they remained for early 20th Century archaeologists to discover. There were 14 skeletons, ranging from a child of two to a man of 70, with familial likenesses, and bashed-in skulls and severed limbs.

As the Dark Ages descended, Saltburn was too remote for anyone to be bothered with, apart from a hermit who tucked himself away there in 1215.

The coming of the industrial age awoke Saltburn. In 1615, alum – necessary for fixing dyes into cloths – was discovered in the local shale. The rock was mined, slow-burned for months and then doused in liquid ammonia to create alum. There were two sources of ammonia: the ashes of burnt seaweed and human urine.

What scenes there must have been at Saltburn in the 17th Century. At low tide, ships bearing casks of urine from London would beach themselves amid the pungent smoke wafting from the piles of burning seaweed.

The urine would be unloaded, alum would be taken onboard and the ship would refloat on the high tide and sail for London.

The alum trade faded out after a century, and remoteness closed in once again. A historian wrote in 1846: “Saltburn is shut out entirely from the world, into a nook or corner of creation, with lofty hills screening it from the south, and almost swallowed up by the seas on the north.”

One type of man thrived in seclusion: the smuggler. In 1750, the excise duty on a gallon of imported brandy was more than the average weekly wage. There were similar taxes on gin, tea, tobacco, coffee, playing cards, chocolate, pepper, lace, oars and even spinning wheels – items without which no life is complete.

With Britain’s navy distracted fighting the French or the Americans, smuggling ships put ashore amid Saltburn’s seclusion and their precious cargoes quickly disappeared into hidden cellars, secret tunnels and dark glens.

THERE was by now a row of single- storied fishermen’s cottages at the foot of Huntcliff and four pubs: The Seagull, the Dolphin, Nimrod and, the oldest of them all, The Ship. The pubs were the focal point of the illegal trade, where Revenue- man brawled with smuggler.

John “the King of the Smugglers” Andrew was landlord of The Ship from 1780. As many tales exist of him outwitting the law as of Robin Hood outwitting the Sheriff. “Andrew’s cow has calved” was the phrase indicating that a ship packed to the gunwales with illicit goods had anchored in the bay; “Jennie’s coming” was the code as far away as Osmotherley to say the goods were on their way.

The Newcastle Chronicle of December 23, 1769, reported that at Saltburn “the smuggling trade was never carried on to so great extent as at present.

The great number of country people that daily attend the coast (and who seem to have no other employ but to convey off goods) is incredible”.

Andrew’s luck ran out in 1827 when he was captured, heavily fined and imprisoned in York castle.

The smuggling age was over; the railway age was just leaving the station.

Henry Pease, of Stanhope Castle and Pierremont, in Darlington, was the youngest of the sons of Edward “father of the railways” Pease. Henry was in his pomp in the late 1850s, with his textile mills in the centre of Darlington, his extravagant homes and his equally extravagant railway plans, including driving a track over the Pennines from Barnard Castle.

His brother, Joseph, was driving lines into east Cleveland to the ironstone mines that were the beginning of Teesside’s steel industry. In 1844, Joseph had built himself Cliff House on the seafront at Marske and, in 1848, the Peases’ Stockton and Darlington Railway had been extended from Middlesbrough to Redcar.

On July 23, 1858, Parliament had granted the Peases permission to extend from Redcar through Marske to the clifftop above the smugglers’ former haunts of Old Saltburn. Ironstone had been mined at Warsett Hill, thrown off Huntcliff and loaded onto ships from the beach, so the Peases’ line initially went in search of lucrative minerals.

However, in the summer of 1859, Henry was staying with Joseph in Marske. Henry had just returned from the US where he had seen how towns sprang up in the wake of the railroad. He was also aware of how Redcar had become “a fashionable watering place of a quiet kind” since his own railway had touched it a decade earlier.

Henry returned to Cliff House one afternoon “heated and exhausted and late for dinner”, his wife Mary recalled.

“He explained he had walked along the sandhills to where the burn, which gave the name of Saltburn to a few fishermen’s cottages under the cliff, met the sea. And that, seated on the hill-side, he had seen, in a sort of prophetic vision, on the cliff before him, a town arise, and the quiet, unfrequented glen, through which the brook made its way to the sea, turned into a lovely garden.”

It was some vision.

The reality of Saltburn was described by the Middlesbrough Weekly News in 1860: “There is a row of dirty derelict cottages whose broken and musty windows, like blind eyes, stare cheerlessly out to sea. In front of these we have the shingle and wreck of various storms.”

Still, exactly 150 years ago this week, surrounded by two Darlington architects, two Cleveland builders and their bricklayers, the visionary Pease made a start on Alpha Place.

“Mr Pease remarked that this was only the commencement of what would probably hereafter be the resort of those persons who were in the happy position that they could spend the summer months at the seas-side, to inhale the sea-air or enjoy themselves in rational amusements,” said the D&S Times. “Although the beginning was only on a moderate scale, he had little doubt but that some who were present, who were younger than himself, would live to see things on a much larger scale.

“Three cheers were raised in order to dispel the tameness of the proceedings, which terminated by Mr Pease paying his footing.”

• Memories will be following the 150th anniversary of Saltburn throughout the year.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here