The tallest monument in Hurworth churchyard leans at an angle that is becoming increasingly drunken with each passing year. This is ironic, really, as it was erected in 1861 by the local Temperance Society, which was so against alcohol in the village that it has left two other monuments to its fervour – a hall and a dentist’s surgery.

THE earliest temperance driving force in Hurworth was a fearsome Methodist matriarch, Margaret Maynard, whose name appears first and foremost on the All Saints monument.

She was a “Ranter” – an evangelical Primitive Methodist.

She composed a couplet advising young girls how to maintain their honour:

If a maid would keep a good name

She would bide at home as if she was lame.

Mrs Maynard’s Primitives built a chapel in the east end of the village, in 1835, on “the old barracks” – not a military reference, but a French word meaning “hut or shed”. Hurworth 200 years ago was a linen village with hundreds of weavers working looms either in damp subterranean rooms dug into the riverbank or in temporary tumbledown shacks, or baraques.

Such was the squalor of their working conditions, some of the weavers turned to drink.

Mrs Maynard tried to divert them from such a ruinous cause, first with her chapel and then by forming the Hurworth Teetotal and Prohibition Society, which held its inaugural gala on the village green on Whit Tuesday 1852.

Quickly, the gala became the social highlight of Hurworth’s year and who, in all honesty, could have resisted the allure of the 1861 soiree which was addressed by Dr FR Lees of Leeds?

The Darlington Telegraph said the guest speaker was “the great expounder of the Temperance question”, and it reported: “Dr Lees, in a most masterly and comprehensive speech of an hour-and-a-quarter, reviewed the whole phases of the great temperance movement: Entomological, Scientifical, Experimental and Biblical.”

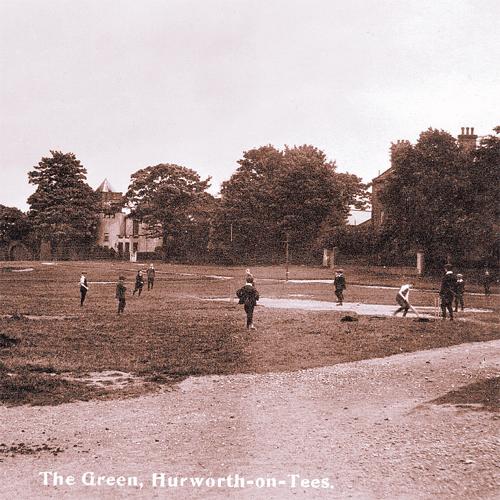

The 1863 gala was attended by 1,000 people – many of them day-trippers from Darlington and beyond – who were drawn to the sound of the brass band and the sight of the cricketers on the green.

With such sizeable support, the society wanted permanent premises. In early 1864, it asked 26-year-old architect GG Hoskins to design it a meeting hall.

Hoskins had only just come to the area to work as the renowned Alfred Waterhouse’s clerk of works on the great Pilmore Hall (now at the centre of Rockliffe Hall hotel) that was being built for Alfred Backhouse at extraordinary cost at the west end of the village.

Despite a major falling out with Waterhouse’s other employees, who nicknamed Hoskins “The Great Darlington Frog”, the young man was clearly enjoying himself in Hurworth: he named his first son Harry Pilmore Hoskins.

The £650 Temperance Hall was to be Hoskins’ first solo project, starting a career that would see him design some of south Durham’s most interesting and Gothic buildings, from the King’s Head Hotel, in Darlington, to Middlesbrough Town Hall.

Hoskins must have pulled a few strings at the Pilmore building site, because in March 1864, Joseph Pease – the greatest man in south Durham – laid the temperance hall’s foundation stone “with great eclat” almost opposite the ranters’ chapel.

WITH great ceremony, the hall was opened on December 27. “The weather was magnificent,” reported the Darlington Telegraph.

“The sun shone brilliantly on the clear frosty atmosphere, so that the village and the surrounding scenery seemed to have put on holiday garb.”

It continued: “The style of the building is of a most effective Gothic character, and something quite new in this country.”

For this first commission, Hoskins combined cream and red bricks to lift his austere exterior design, while around the ceiling inside he painted “appropriate temperance mottoes...

beautifully illuminated in the mediaeval style”.

They weren’t so much mottoes as essays: “A good cause when violently attacked by its enemies is not so much injured as when defended injudiciously by its friends...”

reads the first of four.

Local people were impressed, though. “The architect who designed a building of so much beauty that could be erected for so small a sum must be possessed of as much ingenuity as taste, and we heartily congratulate Mr Hoskins on the success of his work,” said the Darlington Telegraph.

The day-long celebrations began with a morning parade through the village led by the architect and Alfred Backhouse, of Pilmore Hall, followed by the Northallerton Temperance Brass Band.

Temperance was obviously a cause close to Mr Backhouse’s heart. One of his rare public utterances as a member of the board of health was on the possibility of a ban on the sale of alcohol in all Darlington – an opinion that did not endear him to the publicans who, as Echo Memories explained last week, were pursuing him through the London courts for being “the illegal member”.

Opening the Hurworth hall, Alfred told the teetotallers: “I think drunkenness is the greatest curse that inflicts this nation, and the greatest misery that it has to suffer. I trust, however, that the efforts you will make in the cause will be beneficial... The hall certainly is a signal success.

(Cheers.)”

The opening was followed by a bazaar, a public tea for 150 people and a public meeting for which “the hall was again crowded even to inconvenience”.

Long religious speeches promoting temperance were made, including one by a Mr Johnson, a temperance missionary, who said the new hall “will be like an Armstrong Gun – it will blow down the signs of the public houses in the village”.

AFTER this success, the society moved to more practical methods. In November 1878, Alice Scurfield, from the village’s leading family who lived in Hurworth House, built the Onward Coffee Tavern almost opposite the hall at a personal cost of £1,200.

Onward Taverns were spreading quickly across the North-East on the back of the temperance bandwagon and also because of the trendiness of the new tastes of coffee and cocoa. Hurworth’s Onward was the first in the district – Darlington’s first arrived three years later.

The Darlington and Stockton Times explained the need for the Hurworth initiative: “The attractions which the public house has for young men, and the consequent temptation to imbibition of intoxicating liquors, with the habits of intemperance induced thereby, have been a matter of regret to many benevolent people. Various methods have been attempted as counter-attractions, but from various causes these have not been so successful as could be wished. One of the principal reasons for their failures has been the dull and altogether uncomfortable character of the substitutes, which have had the effect of repelling, rather than inviting customers.”

The Hurworth tavern set out to be attractive. Downstairs was a reading room with all the latest newspapers; upstairs was a billiard room and a library. Chess and draughts were encouraged, gambling was banned, but smoking was reluctantly allowed.

Most impressive of all were the kitchens, in which were brewed “the large cups which will contain the beverage which cheers, but not inebriates, to do good to thirsty souls”.

To get the purest water, a 12ft well had been bored beneath the tavern. Water was drawn up it to the top of the house where a covered cistern contained 1,000 gallons.

Membership of the tavern was five shillings a year for adults and three shillings for 15 to 18-year-olds. On the opening evening, 18 gallons of coffee were sold, and Miss Scurfield, assisted by Mrs James E Backhouse, of Hurworth Grange, personally waited on the 56 workmen who enjoyed a celebratory dinner.

The Onward Coffee Tavern marked the high point of the temperance movement.

The tavern lasted a decade, and is now a dentist’s surgery.

The last name was inscribed on the churchyard memorial in 1902, and the Temperance Hall closed in November 1920 and is now the village hall.

As an Armstrong Gun, it proved unsuccessful – the three public-house signs that it threatened to blow away are still swinging, all just about within sight of the drunken monument.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here