Stapleton is a village with history, heritage and humps. The Way to the Stars is a film with Blenheims, Bedale and a bloke called Boston. Echo Memories looks at them both and divides the rest of its time among mathematicians.

STAPLETON straddles its road to the south of Darlington as if the passing of the centuries, like the passing of the traffic, mean nothing to it. Quietly rural, with the River Tees running nearby, it looks unperturbable. But it has certainly had its moments:

9th Century: The original Saxon village of Stapleton – pronounced Stapplton – is said to have been in a field near where the River Tees performs a sharp U-turn.

13th Century: Nicholas de Stapleton, descended from a family that came over with William the Conqueror in 1066, was a rising force in Yorkshire. He gave some land at Stapleton to St Agatha’s Abbey, at Easby.

How the monks must have been happy, until they discovered that it was now their duty to maintain a ferry boat over the Tees at Stapleton. The boat worked alongside an ancient ford.

1314: Miles de Stapleton was one of Edward II’s most trusty lieutenants. He made him Lord Stewart of the Household, one of the most powerful men in the country.

But a year later, Miles was sacked by Edward, who replaced him with a man reputed to be the king’s lover, Piers Gaveston. Miles, a proper knight, remained powerful, fighting in Gascony and besieging Scottish towns as the fancy took him until the Scots got the better of him and he was killed on June 24, 1314, at the Battle of Bannockburn.

14th Century: There were two chapels at Stapleton: St Leonard’s, which belonged to St Agatha’s Abbey, and St James’, the domestic chapel of the Stapleton family. The Stapletons’ large house was probably to the north of the village green in a field with a wonderful collection of lumps and bumps that cry out from a lost age. The house had either a moat or a fishpond, and was pulled down in about 1820.

14th Century: A medieval bridge over the Tees at Stapleton was washed away by a flood. It is after this bridge that the village’s Bridge Inn is said to have been named.

1616: The Stapleton family disappeared and the new landowner, George Pudsey, received a grant from James I of £160 a year for as long as his wife, Faith, lived. This was a reward, for George’s father had lent Mary, Queen of Scots £1,000, which she never repaid.

1640: After the Scots had captured Northumberland and Durham, there was a soldierly skirmish at Stapleton. English troops chased the Scots three miles to Croft-on-Tees. Seeing the bridge there guarded, the Scots jumped into the Tees.

Several drowned.

17th Century: With the decline of Stapleton’s landed gentry, its chapels fell down and it was incorporated into a parish with Croft, which had the main church. A Corpse Walk developed from Stapleton, along the top of Monkend Hills, over a packhorse bridge and into Croft churchyard. For the pleasure of crossing Croft church land, the corpse had to pay the rector of Croft one shilling.

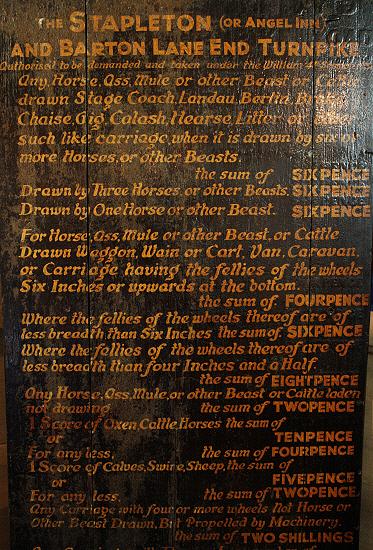

1833: The turnpike road – a toll road – from Scotch Corner into Darlington was built, changing the character of Stapleton for ever. The turnpike crossed the Tees at Blackwell Bridge, which was built on foundations of bags of wool. This was a common method of the day for bedding the pillars in evenly.

It was devised to carry a bridge over the Thames by one of the greatest mathematical minds of the 18th Century: William Emerson of Hurworth.

Until recently, a toll board was displayed in the Bridge Inn apparently showing how much it cost to use the turnpike road.

However, evidence posted on the Echo Memories blog from Melvyn Carter in Bohai Bay, China, suggests that the board really relates to the cost of travelling what is now the A167 from Darlington to Northallerton.

SO many people have been in touch about the 1945 film The Way to the Stars. It was filmed in Bedale, Northallerton and Catterick and is fondly regarded as one of the best Second World War films.

“You’ve mentioned several stars, but not the main performers: the aircraft,”

says Pat Woodward, in Durham City.

“The shot of a flight of Bristol Blenheims coming over the church at Bedale early in the film is a most evocative sight, especially for an old airman like me whose first air experience flight in 1941 was in an operational Blenheim of 82 Squadron at Bodney, Norfolk.

“In the films there are glimpses of Douglas Bostons, Hawker Hurricanes, Lancasters, dozens of B17 Flying Fortresses, and even a dear old Avro Anson.”

He also highlights Stanley Holloway’s performance as the hotel bore, plus a part played by Bill Owen, who later became Compo in Last of the Summer Wine.

There was an early part for Jean Simmons, who appears with the band at the station dance, but Winifred Woodhouse, in Darlington, believes the dance was set at Solberge Hall, rather than Constable Burton Hall as previous articles have suggested.

Mrs Woodhouse remembers that lots of local names were written into the film. There’s a character called Penrose, after George Penrose, one of the most influential members of the farming community; there’s a Boston, after Johnny Boston, who had a confectioner’s shop in Northallerton High Street and whose daughter married into the Barker family; and there’s a Clark after Nobby Clark, a high-ranking police official.

Mrs EM Smith remembers the film being made: “The car passed, drew up in front of the Golden Lion, Northallerton, and John Mills and Michael Redgrave got out. I was standing with my friend on the opposite side of the road.”

Mr D Scott, of Shildon, says: “I went to work as a conductor on the buses in Richmond in 1947. It was said that parts of the film were made in Catterick Village with the Red Lion pub being the focal point.

“In Catterick Village was a small cafe owned by Joe King, and he got to know all the stars. His walls were festooned with autographed photographs of them. I wonder what happened to those pictures?”

Winifred Woodhouse, of Darlington, believes that the dance was not held at Constable Burton Hall, as suggested here, but at Solberge Hall. She is also struck by how many of the characters in the play take their names from Northallerton dignitaries of the day.

Roger Birchall emails to explain why the film’s name was changed to Johnny in the Clouds for the US.

“In the film there is another plot line which features a squadron of American bomber pilots.

One befriends Toddy in a platonic way after she loses her RAF husband in a plane crash over France,” he says.

“The American is a hit with the local children as a conjuror at a church party, but tragically, he is also killed landing his plane, choosing to stay with it rather than let it hit the local village.”

A poem, titled For Johnny, was read at his funeral: Do not despair For Johnny-head-in-air; He sleeps as sound As Johnny underground.

Fetch out no shroud For Johnny-in-the-cloud; And keep your tears For him in after years.

Better by far For Johnny-the-bright-star, To keep your head And see his children fed.

Says Roger: “The poem still gets me, as a baby boomer, every time. No wonder the Americans renamed the film.”

ECHO Memories has been telling recently of a number of 18th Century Durham mathematicians. Although they pursued their studies separately, they did help one another.

For example, John Bird (1709-76), of Bishop Auckland, assisted Jeremiah Dixon (1733-79) of Cockfield, who was 24 years his junior, get an interview with the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich in 1761. Probably due to Bird’s recommendation, Dixon sailed through the interview and ended up sailing to the Cape of Good Hope to measure the transit of Venus across the face of the sun – it was hoped that these measurements would reveal the distance Earth is from the sun.

William Emerson (1701-82), the sundial star of Hurworth, also assisted Dixon, who was 32 years his junior. While discussing the finer points of mathematics, Emerson – who enjoyed an ale – introduced his young protege to the beer.

In 1760, Jeremiah was disowned by his strict Quaker parents, it is said, because of his drunkenness.

Is it coincidence that the following year Bird fished him out and set him sailing?

Jeremiah went on to greatness, as the Mason- Dixon Line in the US testifies, but it is said that he never overcame his fondness for drink, hence his comparatively early death aged 46. He is buried in Staindrop’s Quaker cemetery.

‘GOOD to see the articles on the treasures from history that we have in County Durham but which are barely known about,”

says David Cassie, of the Cares Group, the social work company of Byers Green.

“We renamed one of our properties in Byers Green Thomas Wright House.”

The observatory of Thomas Wright (1711-86) dominates the village of Westerton, and he was associated with the other mathematical pioneers.

Mr Cassie says: “Nineteenth and 20th Century history always dominates the North-East, and while it has a hugely important place in the scheme of things, older history is passed by.

“Binchester Roman Fort, with one of the best examples of a Roman bath house in the world, gets 4,500 visitors a year (because it’s hardly ever open).

“If it was in Oxford or Cambridge it would get four million.”

Do we make enough of our treasures from history?

DENIS COATES, in Hurworth, wonders whether anyone else recalls “Molly Dolly” who was at her prime in Darlington around the time of one of this column’s great heroes, Geordie Fawbert.

“Molly Dolly was a travelling washerwoman (hence the her name dolly) who pushed a large boxshaped barrow with iron wheels around the back streets in the area where we lived in Corporation Road,”

says Mr Coates, going back to 1939 when he was five years old.

“She was not very tall and about the same build as Dawn French. She wore a full-length black dress, men’s black boots with studs, a white apron and a man’s cloth cap.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here