This week, Memories looks at South Church, an ancient community one commentator described as being 'smothered by some of the ugliest features of industrial growth ever to be found'

SOUTH Church always seems to be in danger of inundation. The River Gaunless, on its southern edge, is forever threatening to swamp its properties, and Bishop Auckland, on its northern boundary, is always threatening to spill across the A688 and overwhelm its identity.

Indeed, its identity is already compromised because its proper, posh name is Auckland St Andrew – or St Andrew Auckland – but it is known by its 150-year-old nickname of South Church.

But a new book, launched tomorrow, by local historian Tom Hutchinson, tells how once it was something very important in its own right – which is why it boasts the largest parish church in the county and the oldest continuously occupied residential building in Durham.

In 1083, the Bishop of Durham, William de St Carileph, ejected some monks from Durham Cathedral. They weren’t sufficiently holy enough for Bishop William – the bishop who designed much of the cathedral we see today – because they had naughty things like wives and children. In their place, he installed celibate monks from Jarrow and Wearmouth, and the displaced canons were fired off to Darlington, Norton and Auckland St Andrew.

There had been a fairly important church at Auckland St Andrew on the banks of the Gaunless for several centuries, probably because it was the last stopping place for pilgrims from the North-West as they journeyed over the Pennines to the shrine of St Cuthbert, in the cathedral.

The canons chose to settle there with their families, and turn it into a religious college. They thrived, and became quite wealthy, with land stretching from Evenwood Gate to Spennymoor.

In the 13th Century, another bishop, Anthony Bek, allowed them to build, on the south bank of the Gaunless, a deanery – now the oldest continuously inhabited house in Durham.

In turn, the canons and their dean rebuilt the old church of St Andrew over the river, making it 157ft long and 80ft wide, to suit its purpose as a grand place of learning.

The canons are said to have connected the two buildings by a tunnel that must have gone under the Gaunless before coming out in the pulpit.

And, just for good measure, they put a wooden spire on the church’s tower.

For the next three centuries, the canons behaved themselves, but then between 1536 and 1541 Henry VIII – the naughtiest of them all – dissolved the country’s monasteries. The Deanery became the Crown’s property and was turned into a farmhouse, and the collegiate church became a more humble parish church – the largest of its kind in the county.

Time slowly erased the memories of the deans days – the nearby Dene Valley, which has the villages of Eldon and Close House in it, was really the Dean’s Valley but as the dean was forgotten so the valley’s name changed – and Auckland St Andrew became just another village.

Its population early in the 19th Century was a little over 100. Then came railways and coalmines and another form of inundation: people.

The population tripled between 1821 and 1831 and then quadrupled in the next decade. Terraces of houses – and plenty of pubs – sprung up.

It irrevocably changed the character of the village; it even changed the village’s name. To the newcomers – in 1851, half of the inhabitants had been born outside County Durham, many in the Yorkshire Dales – having Bishop, West, St Helen and St Andrew Auckland was too confusing. St Andrew had a very large church and was to the south of the big town of Bishop Auckland. It obviously became known as South Church.

By the start of the 20th Century, up to 5,000 men and boys were employed in the pits and drifts around South Church, and the village’s population peaked at 3,923 in 1921.

But because it had been among the first places to jump aboard the railwayinspired industrial boom, it was one of the first places to experience the decline of what had created it, and the desolation that followed.

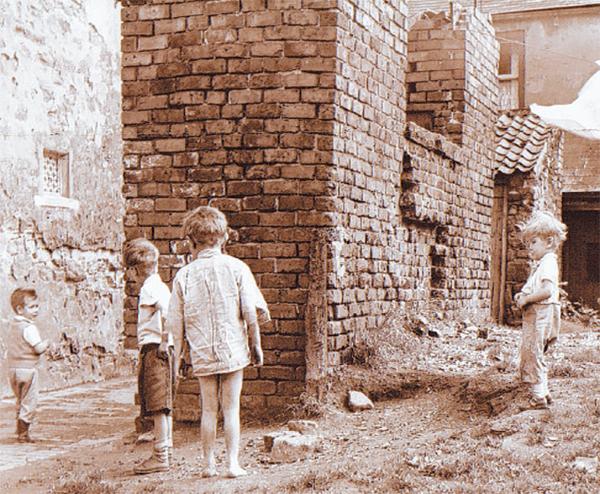

In his book, Tom Hutchinson quotes from a university thesis written in 1940. “South Church has been smothered by some of the ugliest features of industrial growth ever to be found,” wrote student Vera Temple. She described the former mining terraces as being “low, two storey buildings with two or three rooms…arranged in a jumbled fashion around courtyards and alleys…the streets have never been made up and the houses are too close together”.

Pictures in The Northern Echo’s archives from the late Fifties express the astonishment of the photographer that people were still living in such conditions.

Demolition came in the Sixties and pitheaps were landscaped in the Seventies, leaving only memories of a lost way of life, which are rekindled in Tom Hutchinson’s new book.

MINES AROUND SOUTH CHURCH

ELDON COLLIERY

Sunk in 1829 by Joseph Pease, of Darlington. It peaked in 1921 when it employed 1,988, but closed in July 1932. During its 103 years of life, 124 of its miners lost theirs underground.

ADELAIDE COLLIERY

Sunk in 1830 by the Peases.

In 1894, its 520 employees produced 150,00 tons of coal annually, much of which was burnt in its 139 coke ovens. It closed in 1925. In its 95 years, it lost 46 of its workers. Nine of its fatalities were 16 or under; one was only 12.

BLACK BOY COLLIERY

Sunk by Nicholas Wood, of Newcastle, in 1830, and presumably named because it was a dusty place that caused its miners to turn black. A big concern from an early date – 200 were employed there in 1844 – it peaked in 1914 with a payroll of 309. It closed in 1939, with 56 people having been killed, including, on January 21, 1851, 11-year-olds William Hogg and John Greener. The explosion happened at 3am when most 11-year-olds today are safely in bed. In the 1870s, the Black Boy banner featured a poem called Justice: Miners throughout the land Join in one social band; If you would happy be, Free from all slavery, Banish all knavery, And free yourselves.

DEANERY COLLIERY

Sunk on February 4, 1834, by Joseph Pease, but it never employed more than a few score and continued into the early Fifties. All four of its fatalities happened on the same day – July 14, 1837. The oldest was Matthew Brown, 16, along with the Sunter brothers, Ralph, 13, and Robert, 12, from New Shildon, and ten-year-old Robert Storey, from Old Shildon.

WOODHOUSE CLOSE COLLIERY

Sunk in 1835 to get the remaining coal out of an ancient working at Coppy Crooks. In the 1870s, its banner featured a little ditty about mining life: The dangers that miners have to undergo, Are many and fearful, by this you may know The maximum employment was 93 in 1930 and it closed in 1934.

AUCKLAND PARK COLLIERY

It started in 1864 as the Machine Pit of Black Boy, but grew into a huge concern with 430 coke ovens that turned the night sky orange.

In 1902, it employed 1,236, although after the Second World War it supported only a handful of workers and it closed in its 100th year, having been the scene of 97 deaths.

IN early August, Echo Memories was looking at a railway bridge over the Gaunless to the south of Bishop Auckland. It was off Green Lane, on the 1856 Shildon Tunnel loop line, and referred to as the Water Bridge.

David Shevels got in touch: “As far as I know,” he says, “the only Water Bridge nearby is at the other end of Shildon Tunnel and used to carry a beck over the lines.

The OS maps don’t show any beck there now, but the bridge is still there.”

THAT item has been on the fantastic Echo Memories blog, which is regularly updated with snippets and feedback from the column.

The blog also reported the winners of the competition to win one of five copies of Michael Richardson’s new book, Durham City Through Time (Amberley Publishing, £12.99).

Many thanks to everyone who entered. The competition wanted the surname of the family that ran Vaux brewery for three generations. The answer we expected was Nicholson, but far more people put Vaux – and they, too, were right.

Three generations of Vaux, starting with Cuthbert in 1837, did indeed run the brewery, as did three generations of Nicholsons, starting with Sir Frank in 1898.

The Echo Memories version of the brewery history will be posted on the blog this morning.

The names drawn out of the hat to win the books were: M Colwell, Ushaw Moor; Sandra Spence, Tow Law; Francis Grant, Durham City; F Watchman, Bowburn; Lynn Hanson, Merryoaks, Durham.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here