The Romans went to Lavatris and founded a camp. Henry II built a castle to keep the Scots at bay. Cattle merchants and travellers drank in its inns. The railway dealt it a blow, but this village beneath the Pennines managed to survive. And now, almost 2,000 years after the legions departed, the show still goes on...at Bowes.

ABOUT 140 years ago, the village of Bowes could feel the turning of the tides of time.

It had stood for centuries at the foot of the Stainmore pass, where footmen, horsemen, centurions, carriages and coaches all geared themselves up for their final ascent of the Pennines.

From the comfort and hospitality of Bowes, they rose nearly 400ft to Stainmore summit on one of England's bleakest roads, before dropping down into the welcome of Westmorland.

The Romans had passed that way, creating a camp called Lavatris where Bowes church is today. Still on the moors around the village are the remains of a Roman aqueduct that piped fresh water into this vital refuelling station on the trans-Pennine route.

In Medieval times, Bowes maintained its strategic importance as Henry II built a castle there to prevent the nasty Scots from capturing the Stainmore pass.

In more peaceful times, Bowes continued as a staging post, its inns hosting mail coaches, its blacksmiths preparing their horses.

In those agricultural times, it was not unusual to see trains of bullocks three or four miles long being walked through Bowes.

Since 1244, a market had been held every Tuesday, and once a year, a horse fair was held there "on the Tuesday before the famous Brough Hill fair".

But 140 years ago, the tides of time were turning.

The South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway had connected Barnard Castle with Tebay, in Westmorland, on July 4, 1861, at a cost of £666,879 3s 9d. Spectacular viaducts designed by Thomas Bouch took trains westwards carrying County Durham coal and coke, and eastwards carrying Cumberland iron ore to the blast furnaces of Teesside.

But quickly the trains stole the loads from the road through Bowes. Cattle were loaded into rail trucks, and letters put into mail vans.

Passengers found it quicker and more comfortable to travel by train.

So in Bowes, where the markets and fair had already fizzled out, pubs and blacksmiths struggled as times changed.

The Right Honourable Thomas Emerson Headlam, of Gilmonby Hall, near Bowes, decided an agricultural show would remind Bowes that it was still the capital of its district.

Agricultural shows were all the rage, and one in Bowes, figured Mr Headlam, would improve trade and would encourage his tenant farmers to improve their stock.

The first Bowes show was held on September 21, 1869; the 121st will be held next Saturday, September 13.

Mr Headlam and his wife, Ellen (the daughter of the exotically-named Major Turner van Straubenzee of Spennithorne, Bedale), marched onto the ring in the showfield next to the Unicorn Inn, accompanied by the judges. Mr Headlam - show president and sponsor - stayed in the ring until the Best Roadster class was awarded. The judges decided that the winner was "an extremely elegant and muscular chestnut mare" owned by a certain Rt Hon TE Headlam. Mr Headlam seems then to have happily departed the ring.

Mr Headlam was born at Wycliffe, on the banks of the Tees, and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge. "He graduated as a sixth wrangler in 1836, " said The Northern Echo in his obituary, a wrangler being one who gains the highest marks. He became a barrister, and was elected Liberal MP for Newcastle in 1847, a seat he held until 1874 when he was defeated "through the factious policy of the Newcastle Radicals who preferred to let in an avowed Tory to a moderate Liberal", according to the Echo.

In Parliament, Mr Headlam rose to be Judge Advocate-General, which allowed him a seat on the Privy Council.

He was Bowes show president until his death in Calais in December 1875, aged 62. People who had seen him at the Railway Jubilee celebrations in Darlington a few weeks earlier had been most concerned by his "wan and wasted looks", said the Echo. The paper said he had "an affection of the liver".

Rather than face the harsh Bowes winter, he decided to seek warmer climes in Italy for the sake of his health.

Sadly, he deteriorated on the train down and only just made it over the Channel.

His body was returned to Bowes for burial.

The show he founded lives on. Now it is known as "the Swaledale Royal" because since 1925, local sheep breeders who specialise in Swaledales have fought hard for its trophies.

Fittingly for a village that can trace its origins to the earliest days of transport, there are also plenty of horse classes including, for the first time this year, one for retired racehorses.

|With thanks to Andrew Bracewell MANY thanks to all who braved the Echo Memories talk at Cockfield church ten days ago; £100 was raised for St Teresa's Hospice in Darlington and more information came to light about the Reverend William Luke Prattman.

He was the vicar of Barnard Castle Congregational Church who owned shares in the Stockton and Darlington Railway. His wife, Dorothea, owned the rights to mines near the Gaunless Va lley village of Butterknowle.

The vicar held the directors of the S&DR to ransom by threatening to vote against their expansion plans unless they built a branchline to his wife's collieries.

The branchline around the foot of Cockfield Fell duly opened in 1830. But by 1835, Dorothea's pits had encountered geological problems and he borrowed £20,000 to overcome them.

It wasn't enough, and he declared himself bankrupt in 1841 owing a staggering £40,000. It doesn't sound much until you convert it into today's values: at least £2.6m. This was probably the biggest bankruptcy ever in the County Durham coalfield.

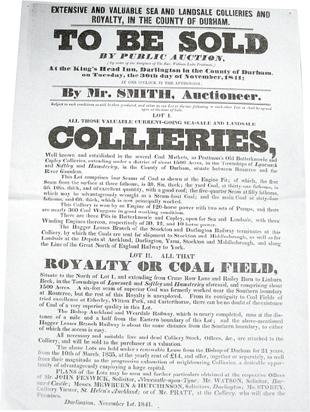

His pits were auctioned at the King's Head Hotel in Darlington on November 30, 1841. "The Haggerleases branch of the S&DR terminates at this colliery, " advertised a poster. "There can be no doubt of the existence of coal of a very superior quality in this lot. " There were plenty of doubts, and no purchaser could be found. The creditors, led by Backhouse's Bank, decided to operate the mines to get a few pennies back.

The disgraced vicar died in time his pits were beginning to make a profit.

By the 1850s, his creditors had enough money to lay a threequarters of a mile long railway track alongside a beck up to a drift mine at Marsfield. In the 1870s, they were wealthy enough to buy two - possibly three - steam locomotives to work the line.

And by the 1890s, they had built 120 coke ovens beside their line to turn their coal into coke (the remains of these can still be seen on the edge of Butterknowle).

During these years, pits and drifts were opened and closed, and tramways and screens were built to carry coal down to the line.

Then, in 1906, the Butterknowle Colliery Company went into liquidation. A new company emerged, but in 1910 the New Butterknowle Colliery Company went into liquidation.

Its locomotives were sold to scrap dealers; its track was lifted; its beehive ovens were never fired again.

There was some mining in the vicar's old mines during the 1930s, but the National Coal Board abandoned his workings in 1950.

MANY thanks also for the kind comments about last week's article about architect GG Hoskins, whose Gothic style has come to characterise the Tees Va lley. It is good news that the owners of his best creation, the fire-ravaged King's Hotel, in Darlington, hope to restore it to its "former glory" within two years.

Hoskins compiled a book of pictures of every building he built. He called it My Works, and presented it to his wife. The book was last seen in public a couple of decades ago.

If anyone knows of its whereabouts, please let us know.

Did it include this piece of "Hoskinian Gothic"?

In 1894, Darlington Council held a competition to find the best design for a new £30,000 town hall.

GG Hoskins submitted this design under the pseudonym "Santa Claus".

It came third.

The council got cold feet and didn't even build the winner.

Writing in 1960 under the headline "Darlington was spared this abhorrence", the renowned historian R Scarr said Hoskins' design was "overwrought with distracting flippancies".

"While appealing to the Victorian mind, it would have horrified the present generation and indeed have lowered the prestige of the self-styled "A thens of the North", " said Mr Scarr.

"Fortunately, Darlington's next civic centre is planned on more practical lines. " It is true that Hoskins' plan, with its concert hall and balcony, is the product of a fevered imagination, but is it any worse than the ugly concrete and steel palace that Princess Anne opened in May 1970?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here