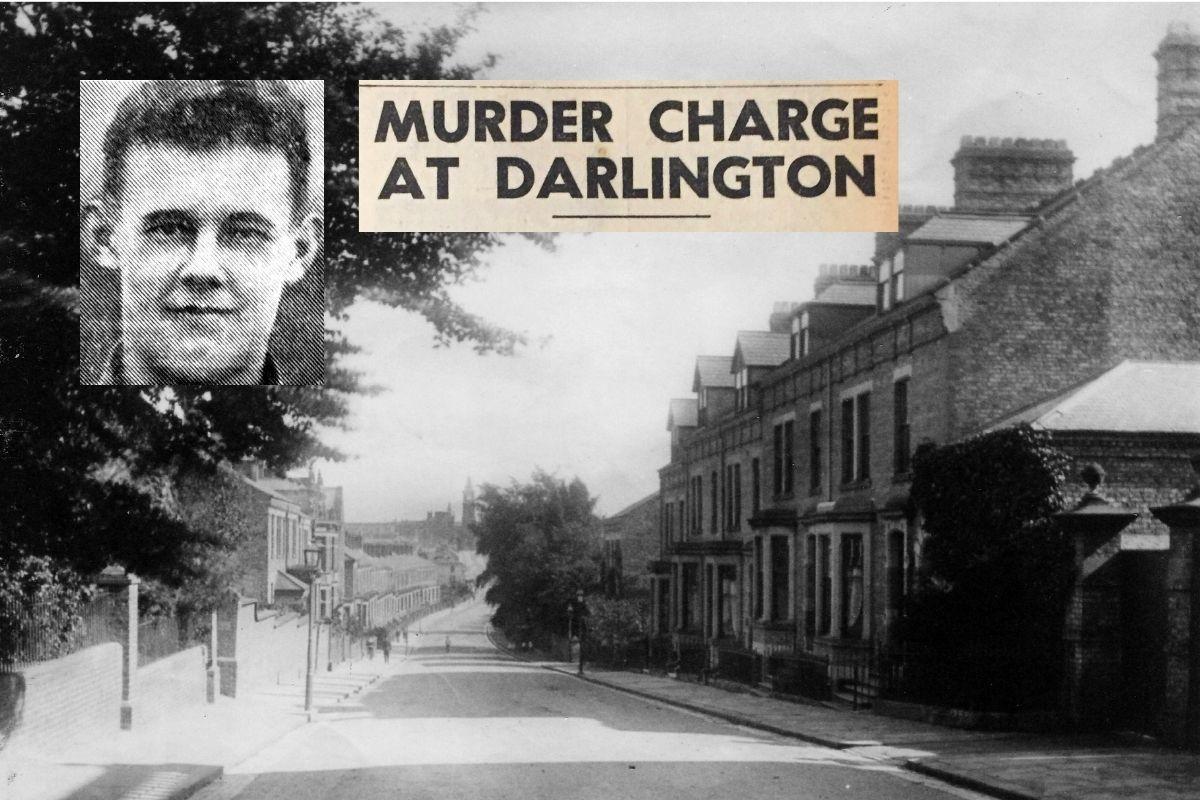

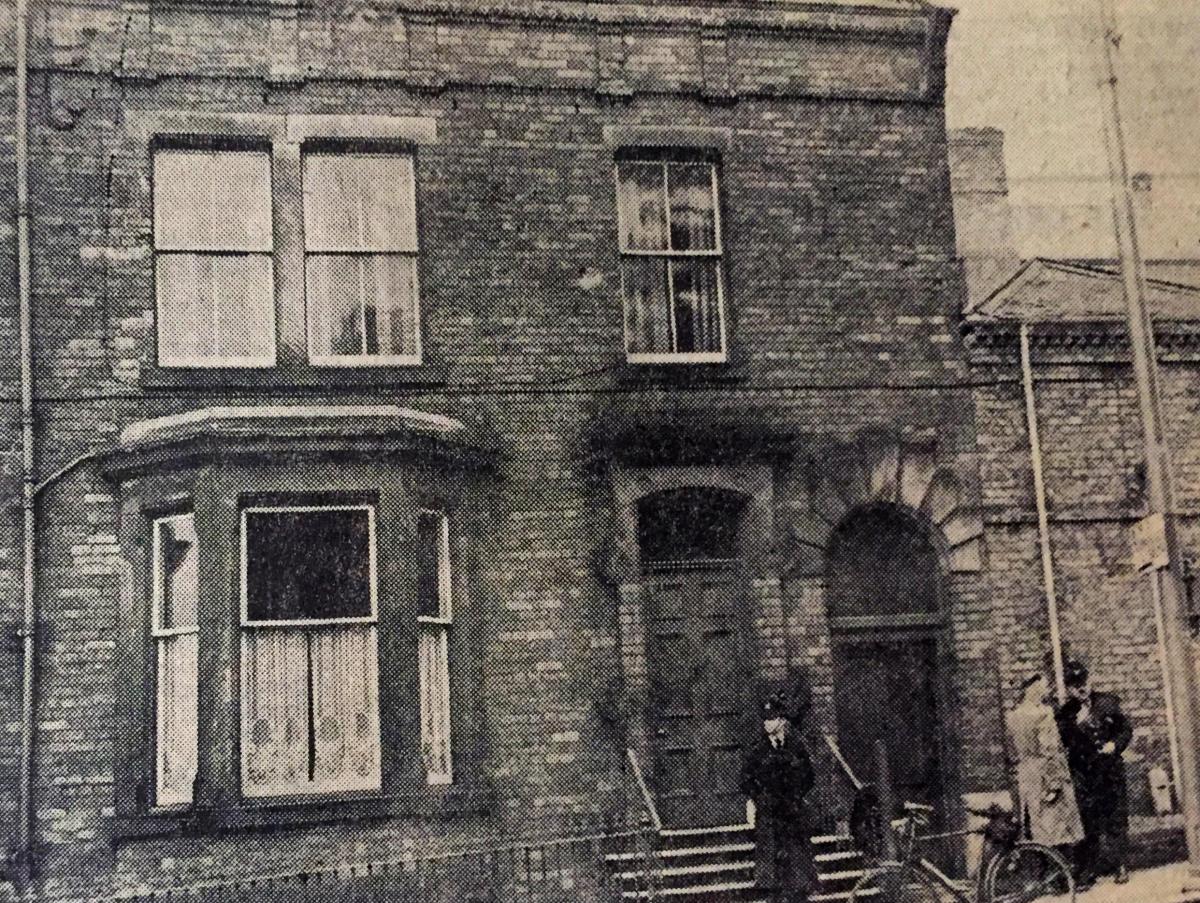

MARTHA ANNE DODD, 83, was “a small, grey-haired. pleasant lady who always dressed smartly and was always very prim”. She sang in the Baptist choir in the church around the corner from her home, No 4, Victoria Road, Darlington, a large mid-Victorian terraced townhouse, in which she had lived for 45 years.

Before the death in 1948 of her husband, who had been an accomplished violinist who had been musical director at the Theatre Royal in Northgate, she had run a domestic servants agency from the house, but now she had retreated to the central floor, keeping the small garden and lawn at the rear in immaculate condition, while letting out the top floor and the basement.

It was here, at about 3.15pm on Wednesday, June 11, 1958, that she was attacked with a hammer. She suffered 19 blows to the head in a "savage, brutal and prolonged attack".

Her body was found in her kitchen later that evening by one of her tenants who became suspicious when her evening newspaper remained unusually uncollected from her letterbox.

The discovery led to the arrest of Brian Chandler, a soldier serving at Catterick, who, six months later, would be hanged at Durham for murder – the last person to be executed there before the abolition of the death penalty.

There seems no doubt that he was guilty of the despicable crime, although in a last desperate attempt to save his skin, he tried to cast the blame in the most lurid terms on two local teenager girls who, his barrister said, were “ahead of him in bloodthirstiness”.

And it was all for £4 that was taken for Mrs Dodds.

The chain of events that led to the tragedy had begun on the Monday, June 9, when 20-year-old Chandler, who came from Middlesbrough, had gone absent-without-leave from the Royal Army Medical Corps. At Bank Top station he met two 17-year-olds, Marion Munro of Hercules Street and Pauline Blair of Chandos Street.

They wanted to leave boring Darlo and head for the bright lights of the city but had no money. Over drinks in the Black Swan in Parkgate, the trio hatched plans which, over the next couple of days, led to a little shoplifting, the theft of a bike, and then a visit to Mrs Dodds, for whom Miss Munro had once worked. She believed the old lady kept £200 in her house.

Mrs Dodds, though, didn’t want any odd jobs doing as her son was about to visit. Outside in Victoria Road, they concluded that the only way they’d get to the money was by knocking Mrs Dodds out; the only way to do that, they agreed, would be to kill her otherwise she’d identify them to the police.

As they parted company that Tuesday evening, the girls believed it to have been a grim joke, and thought little more about it.

Next day, Miss Munro had to sign on at the Labour Exchange at 2.45pm and then, as agreed, met Chandler at the Regal cinema in Northgate at 3.30pm. She was surprised to find that he now had some money; her friend, Evelyn Pigg, noticed that he had blood stains on the rear of his light blue trousers.

After the film, Chandler returned to camp at Catterick where he was arrested on Friday, June 13.

At first he denied all knowledge of the crime. Then he “wished to get it off his chest” how, before going to the Regal, he’d gone to the house in Victoria Road and offered to do some odd jobs for Mrs Dodds. She’d suggested some gardening, and gave him a bucket containing a hammer. She offered him three shillings an hour, which he refused. It blew up into an argument, he said, and when the 83-year-old grandmother attacked him, he had used the hammer in self-defence.

By the time the case came to Durham Assizes in late October, the doctor who had performed the post mortem, Dr John LcLeod Robertson, had demolished the self-defence line by detailing each of the 19 wounds to the head, which suggested a frenzied attack.

However, as the trial began, Chandler withdrew his statement and put forward a new explanation. His barrister warned the jury that “it would be difficult for them to believe what really happened”.

In a plan devised by Miss Blair, he said he and Miss Munro had called on Mrs Dodds to do some gardening. He popped next door to borrow a rake and returned to find Miss Munro attacking the old lady with the hammer.

Summing up, Chandler’s barrister referred to Miss Munro’s appearance in the witness box and said: “If ever there was a young woman of the age of 18 who was physically capable of doing what it has been suggested she had done, then Munro was (that woman). You may think she is a strapping young woman.”

Then turning to Miss Blair, who refuted the new allegation that she had encouraged the attack, the barrister said the jury might have laughed at the title of the film I Was A Teenage Werewolf, but he said the title “came rather nearer reality when you had watched Pauline Blair and listened to her activities”.

The jury took little more than an hour to find Chandler guilty of murder; the judge agreed and sentenced him to death. His appeal to the Home Secretary was rejected, and he was hanged at Durham gaol on December 17.

When the courthouse and prison was built in Elvet in 1810, the first public executions drew huge crowds and great excitement at the gory entertainment. By the time Chandler became the 91st to die there – the 55th in the 20th Century – there was a very different attitude.

"The execution attracted little public interest in Durham," reported the Echo the following day in a report of just six paragraphs.

"The walls surrounding the gardens outside the prison were bare of the normal gathering of onlookers, and as the hands of the clock on the prison tower reached 9am, the hour fixed for the execution, the scene outside remained deserted except for a group of reporters standing in the rain."

Those reporters cannot have known that this was to be Durham’s last execution.

The last executions in Britain were on August 13, 1964, when two murderers, one in Liverpool and one in Manchester, were hanged. In December 1964, the death penalty was abolished for a five-year trial period which became permanent, except for treason, in 1969.

NO 4 Victoria Road had been a doctor’s house and surgery before Mrs Dodds’ 45 years of residence ended in this terrible tragedy in 1958. It then had a different medical use.

“As a young lad in 1961,” says David I’Anson, “I was sat with my mother in the dentists which was halfway up the bank between Sainsbury's and Grange Road, when she said: ‘A woman was murdered in this house a couple of years ago’.”

In those days, at the top of Victoria Road was a large mansion next to the Grange Road Baptist Church where Mrs Dodds sang. This mansion was built in the late 1860s and was called Orwell House before in the 1920s it became the first Grange Hotel.

Moving east down Victoria Road, after the mansion, there was a late 1860s terrace in which Mrs Dodds lived in the second house.

As we told earlier in the year when we began our long stroll down Victoria Road, the mansion and the terrace were cleared in 1976 so that the dual carriageway could be built. The site of No 4 is therefore beneath the block of flats which is today beside the Sainsbury’s petrol station.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel