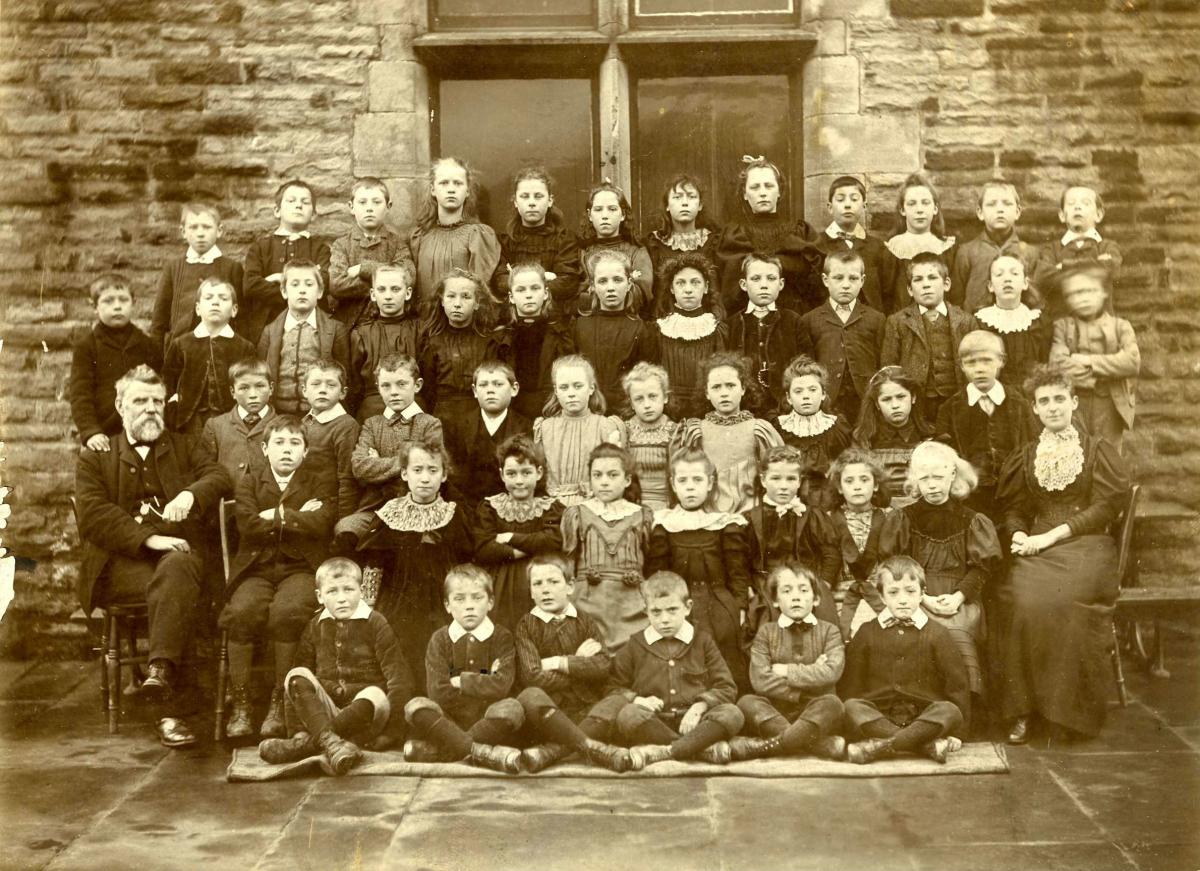

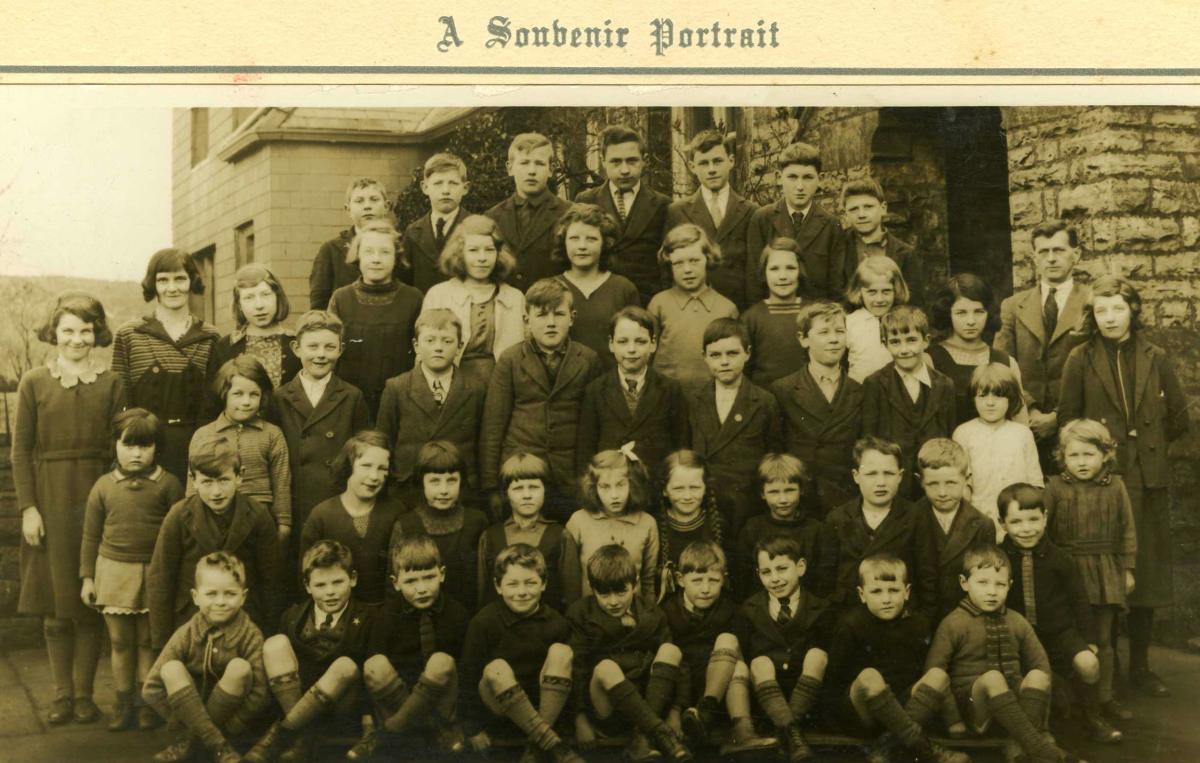

THE wide open spaces of the Upper Dales countryside were once full of schools. Over the centuries, there were dame schools, grammar schools, private schools, barn schools, national schools, Sunday schools, charity schools, board schools…

And there were hundreds of children, especially when the dales became full of leadminers and railway workers to compliment the farm labourers, to attend them – Arkengarthdale school, which shut recently with just five children on its role, once had 239.

On Monday, the latest part of the Story of the Schools project begins. The project is trying to record the history of these schools, and capture the memories of those who attended them before they fade away. It is now appealing for photographs, which will go in an exhibition and mosaic which will open in January.

For centuries, there was a patchwork of informal schools across the dales, funded by local gentry, churches and charities. Some of the earliest were Yorebridge Grammar at Askrigg, founded in 1601, and a Quaker school at Countersett; Fremington, near Reeth, had a school from 1643 and Crackpot from 1765, while there is a story of an informal school in a barn at Angram where the teacher chalked straight onto the stone flags.

The 1870 Education Act, introduced by Quaker WE Forster who spent a couple of his early years working at Peases Mill in Darlington, created local boards of education to provide elementary schools, and in 1880, attendance was compulsory for children between the ages of five and 10 (in 1889, the leaving age was raised to 12, and in 1891, admission became free).

A new breed of board schools came to the dales, some in the most unlikely places: one was built at Lunds, near Garsdale Head, on the Cumbrian border where the Wensleydale Railway once joined the Settle to Carlisle. The school was specifically to educate the children of railwaymen.

However, the people living in these wide open spaces didn’t always value the education on offer to their children.

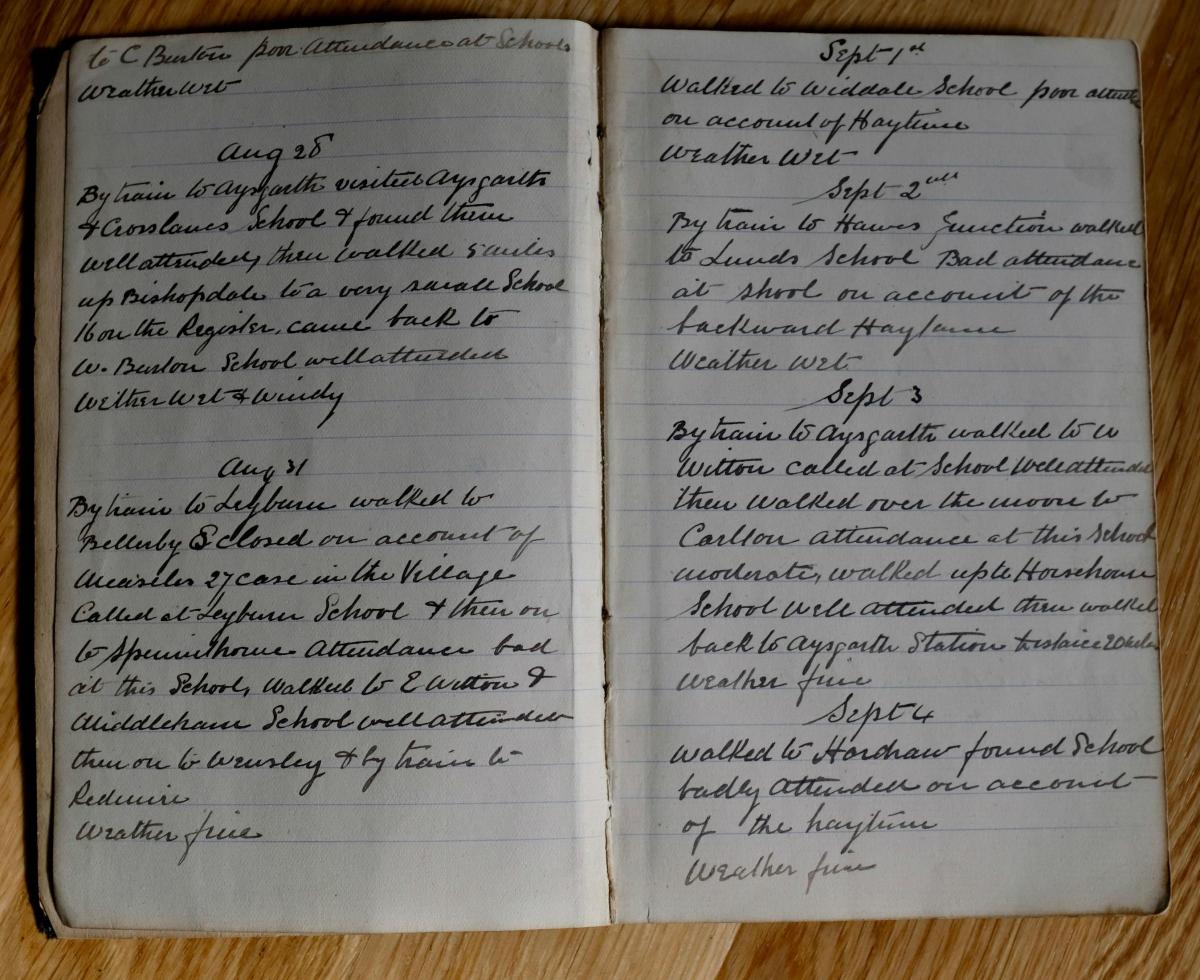

The Story of the Schools project, which is run by The Nash (a former national school) in Hawes and the Dales Countryside Museum, has recently discovered the diary of the Upper Dales school inspector from 1903. It was his job to travel round the upper dales – by train, bike or foot – to make sure the children were attending.

He didn’t write his name in his diary, but he seems to have been based in Hawes, and in the first two weeks of the 1903 autumn term, he visited 28 schools between Lunds, near Garsdale Head on the eastern boundary of his patch, to Newton-le-Willows near Bedale.

His first day of inspecting was August 26, and he took the train to Aysgarth only to find that its school plus the ones at Cross Lanes and West Burton were all shut because of the annual choir and Sunday School excursion to Saltburn.

The following day, he took the train to Constable Burton and walked to Thornton Steward School only to find it closed due to an outbreak of mumps. Then he wandered over to Newton-le-Willows and Patrick Brompton, and found them still on their summer holidays.

On August 31, he took the train to Leyburn and walked to Bellerby only to find its school closed because there were 27 cases of measles in the village.

In the early days of September, he visited the schools at Hardraw, Spennithorne, Widdale and Lunds, and noted that attendance was poor at all of them because of the “backward haytime”.

It was backward presumably because of the weather, and on September 8, the inspector noted: “Weather too wet to turn out. Wrote letters warning parents in Middleham to attend.”

But, little, tiny Horsehouse bucked the trend. He arrived there on September 3 having walked from Aysgarth station to West Witton, over the moor to Carlton and then into Horsehouse which, he said, was “well attended”.

Then he presumably walked back over the moor to get the train home from Aysgarth to write his reports.

Why might Horsehouse, which is very much a one horse sort of a place in Coverdale, have been so well attended?

Horsehouse school was built in 1877 on the site of an earlier school which had been paid for by two local benefactors. High up on the school wall is a poem carved on a stone slab that would have shouted down on the children as they came up the steep side of the dale to class.

The slab says the poem was written by Ralph Rider, who was 89, blind and lived nearby at Deerclose. His poem extols the virtues of charity, education and the benefactors:

The Stranger may here see as he goes by

An Act of most extensive Charity

Which Providence has brought upon the stage.

Such Deeds are rare in this degenerate age

Where sensual Pleasures, Avarice and Pride

Predominate, and Virtue laid aside.

Here’s Treasure laid for ages to endure

From Rust and Moth and Pilfering thieves secure

Which like seed sown upon a fertile soil

In time will recompense the Plowman’s toil.

Posterity may reap the crop and thank

JOHN CONSTANTINE and WILLIAM SWITHENBANK

Perhaps the poem inspired the children of Horsehouse to turn up when harvesting, mumps or measles might have distracted them – perhaps they felt the need to attend in the hope of learning what the hell he was on about…

The Story of the Schools is after any school-related pictures from upper Wensleydale, Swaledale and Arkengarthdale (Horsehouse is, in truth, just outside the project boundaries) from any era.

They can be uploaded directly at thepeoplespicture.com/storyofschools/

For more information on project, go to thenashhawes.org/Story-of-Schools

THE harvest is just about gathered in for another year, but the sight if supersized combine harvesters, with tyres the size of elephants, ploughing through our country lanes inspired Tim Brown to look through the archives of the Ferryhill Local History Society to see if he could find pictures of harvests in days of yore, when harvest was so much more simple – just a yokel and a haystack.

And, of course, he could. Most of these bucolic pictures were taken in the 1920s in Foxton, which is farming hamlet about two miles south of Sedgefield.

The picture which is captioned “Rough Lees Farm”, near Ferryhill – today, the Ordnance Survey maps show Roughlea Farm just to the south of Ferryhill – features what appears to a Richard Hornsby & Sons reaper-binder.

Hornsbys’ Spittlegate Foundry in Grantham employed up to 400 men in late Victorian times building agricultural implements and engines. It made its name in 1867 by patenting the horse-powered turnip pulper, and then in 1885 came the string-binding reaping machine.

It cut the crop and tied it into sheaves (using string rather than troublesome wire). The sheaves were than stacked in stooks to dry for a few days until the thresher came along.

So the reaper-binder was itself a forerunner of the combine harvester.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here