HORNBY CASTLE didn’t just have one icehouse, as most stately homes had – it had three!

The castle is between Bedale and Catterick, and although it strikes a fabulous silhouette on its raised ground surrounded by a deerpark, it is today a shadow of its former glories.

There’s been an important house there since the Duke of Brittany had a moated hunting lodge near the church in 1115, but it really became impressive when Robert Conyers-Darcy, the 4th Earl of Holderness, had the grounds laid out in the 1760s and 1770s with three eye-catching farms – known to designers as “eye-catchers” – strategically placed on ridges. He built bridges, summerhouses and grottoes, and fringed the gardens with a ribbon of ponds which looked like a flowing river.

It looks as if this parkland was designed by Lancelot “Capability” Brown, with the renowned Yorkshire architect and bridge-builder John Carr in charge of realising the designs.

“A further interesting feature is the detached Banqueting House known as the “Museum” which survives as a ruin in the park,” says Erik Matthews, who has been running a volunteer archaeological fieldwork project at the castle for 10 years. “It was designed by Horace Walpole and if you had the appropriate credentials, the Duke would send out for supplies from the local ale house and entertain you down there!”

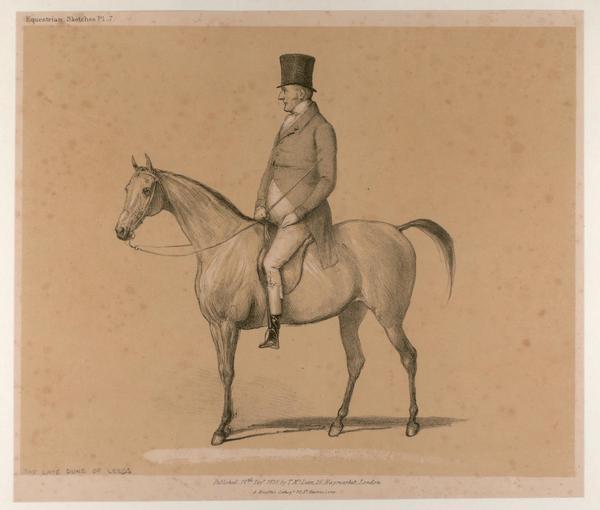

Perhaps the Duke, who served as an ambassador and a foreign minister to George II, didn’t know how rude Walpole was about him in his famous letters, where he referred to him as “that formal piece of dullness”.

The 4th Earl died in 1778, and his heir was the husband of his daughter, Amelia, the 5th Duke of Leeds.

But the 5th Duke didn’t have much time for Hornby as not only was he Foreign Secretary but Amelia eloped with John “Mad Jack” Byron, father of the dangerous poet.

However, the 6th Duke of Leeds made Hornby his principal seat. He populated the grounds with peacocks and pheasants, built an eagle house, and in 1815 he installed a waterfall and started work on his icehouses.

“At an early stage of our fieldwork, we recorded the icehouse which served the house and which lies directly to its rear,” says Erik, sending a photograph of its impressive vaulted interior. “It is unusual in that it is significantly larger than the usual standard size.

“In its heyday in the early 19th Century, the Castle had two other icehouses.

“There was a second one at West Appleton, which served the dairy and was involved in the manufacture of ice creams, sorbets and other desserts for the house, and we have recently located a third one in the park which was used to supply a fishery.”

However, after the 10th Duke of Leeds, a Conservative politician called George Osborne, inherited Hornby in 1895, he became far more interested in greyhound racing, racking up great debts while the castle began to go to wrack and ruin.

“But compared with his father and his son, the 10th Duke was a paragon of virtue!” says Erik. “The 11th Duke, his son, was a compulsive gambler, alcoholic and womaniser whose first wife was a Serbian ballet dancer.

“He had to sell Hornby in 1930 following a “no-holds barred baccarat” game on his motor yacht at Monte Carlo which he, of course, lost.

“Everything went including priceless old masters, furniture and the library which included the original manuscripts of William Congreve, the 17th Century playwright, and the earliest written account of the legends of Robin Hood from the 15th Century.

“The house was due to be demolished and the materials used for road maintenance but part of it was saved at the last minute by one of the asset strippers. This scandal led to the National Trust setting up its scheme to take on country houses and their contents.”

So what remains at Hornby Castle makes an impressive silhouette, but is in fact a shadow of its former glories when a castle owner needed not just one icehouse but three.

HOT icehouse news: we’ve got so many reports of icehouses from County Durham that we could do an entire supplement, which would undoubtedly sell like hot cakes.

From Jane Hatcher’s book, Richmondshire Architecture, we learn of an icehouse on a watery piece of land near the Ure at Jervaulx Abbey.

At Sedbury Park, near Scotch Corner, there are lots of outbuildings connected to the lost mansion: stables, orangery, fruit house and, of course, an icehouse.

At Brough Hall, near Richmond, Brough Beck was dammed to create a lake which would freeze to feed an icehouse which apparently still exists. On January 11, 1838, William Lawson of Brough Hall noted in his diary: “The Ice House was filled today, the ice was not very thick and I shall in future years lay in my stock rather earlier than has hitherto been customary, because when the ice is thicker, say two inches, it requires much more labour to break it up and pulverize it – nearly 50 loads were stowed into the House today.”

And then our attention is drawn to a map of the Solberge Hall Hotel near Newby Wiske which shows an Icehouse Plantation – there must once have been on in there.

Finally, David Shaw gets in touch from Crakehall, near Bedale, to say that an icehouse is recorded in the grounds of Crakehall Hall on the Ordnance Survey maps of the late 19th Century, but it had disappeared by the time the 1913 OS map was published.

There can be few more idyllic scenes in England than the white-clothed cricketers playing on the tree-lined, five acre village green at Crakehall with the perfectly symmetrical hall as the backdrop, and the icehouse was probably the work of Matthew Dodsworth, who inherited the hall in 1763.

He set himself up as a proper squire, dispensing justice – he became very unpopular for jailing a Crakehall pauper, Joseph Benson, for illegally fishing in Crakehall Beck only for Mr Benson to die in prison – and living surrounded by servants who a uniform of blue coats and yellow waistcoats.

He died in 1804, just as the icehouse craze was beginning to die out.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel