With victory just days away, the worst explosion of the war tore through the Aycliffe Angels, killing eight of them. Chris Lloyd reports

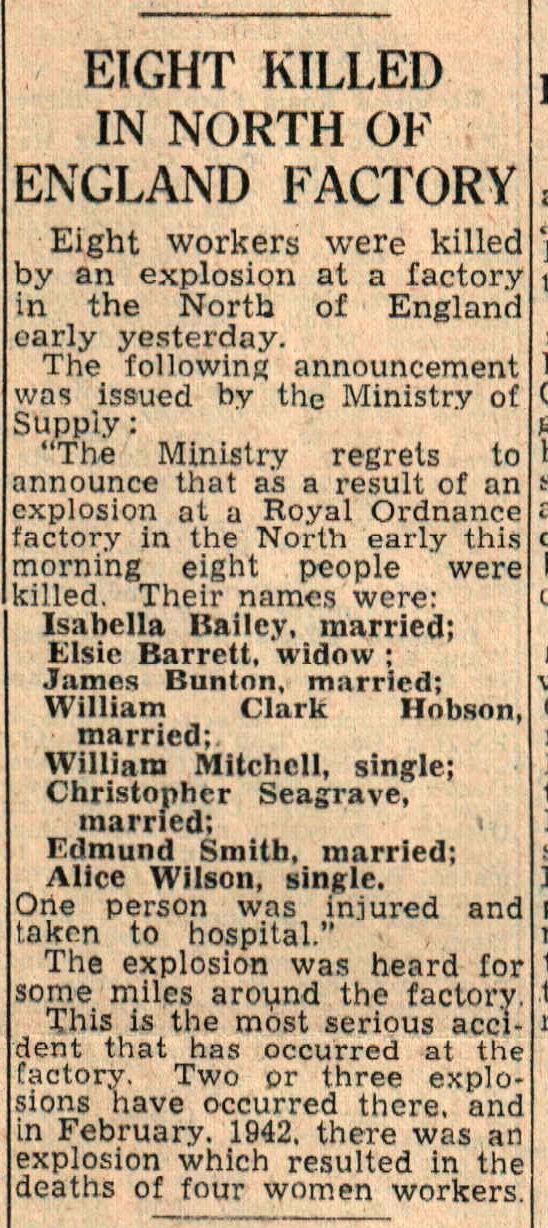

“EIGHT workers were killed by an explosion at a factory in the North of England early yesterday,” reported The Northern Echo on May 3, 1945.

The paper was prevented from printing the full story by the censors, so in four more abrupt paragraphs, it outlined the bare facts of the incident.

It had happened at a Royal Ordnance Factory somewhere in the north, and the eight who died were Isabella Bailey, Elsie Barrett, James Bunton, William Clark Hobson, William Mitchell, Christopher Seagrave, Edmund Smith and Alice Wilson. One unnamed person was hospitalised.

The Echo was then allowed two paragraphs to put the disaster into context. It said: “The explosion was heard for some miles around.

“This is the most serious accident that has occurred at the factory. Two or three explosions have occurred there, and in February 1942, there was an explosion which resulted in the deaths of four women workers.”

The irony of the tragedy was that the victims were producing munitions which, although they did not know it, would never be fired at the enemy in anger, as the end of the war was just six days away.

This was, of course, the biggest disaster to befall Royal Ordnance Factory 59 at Aycliffe, where since 1941, 17,000 people – 90 per cent of them women – had worked around the clock producing munitions.

The factory was built on 837 acres of wet and misty County Durham farmland – ideal to shield it from the prying eyes of the enemy – in 1940-41 at a cost of £7m. About 1,000 buildings were buried into the earth, with earthen berms built around them, because the designers knew that dangerous, explosive work would be going on inside them.

In Darlington, in some secrecy, 350 austerity homes were erected off Yarm Road in five streets named after waterbirds, like Teal Road. These were for the factory’s key workers.

All the other women workers came from within a 30-mile radius, arriving by bus, bike or train in a military logistics exercise – they worked across three shifts to keep the factory operational for 24 hours a day, and so there were constant comings and goings.

The factory was divided into two distinct area: the "cleanway", where the bombs and bullets were manufactured by women in spotless uniforms which featured rubber buttons to minimise the chances of stray sparks, and the "dirtyway" where staff ate or got changed for work.

In the course of four years, they filled 700,000,000 shells – many of the casings were made at the smaller ROF 21 at Spennymoor.

It was such a crucial effort that in 1942, Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited, and, of course, the enemy was well aware of it. On several occasions, the turncoat broadcaster Lord Haw Haw came crackling over the airwaves in his plummy British accent and warned that the planes of the Luftwaffe were on their way to bomb the women.

He warned: "The little angels of Aycliffe won't get away with it."

This must have added to the anxiety of the factory workers: not only were the buildings miserable and cold, but the sound of an aircraft overhead was extremely worrying when you were surrounded by the most combustible materials known to man.

The Luftwaffe seems not to have found the factory in its misty location, but there were plenty of other hazards for the Aycliffe Angels to overcome. The chemicals in the explosive compounds turned their skin yellow. Brunette hair went blonde; blonde hair turned green.

Those who escaped with such superficial damage, though, were lucky. "I saw one girl and she had no fingers on either hand and her face was pitted with black powder marks, " recalled one Angel from Shildon. "People lost limbs. Others lost part of their faces where the skin had been taken off, probably by a detonator going off."

This was dangerous work. There are no records of casualties, but there were many, as the Echo report from 75 years ago this week suggests. There is one story of a girl being blown up on her wedding day.

But there were also inspirational stories. For example, the Angels were supposed to retire when they reached the age of 50, but Mary Dillon, of Low Beechburn, Crook, didn’t think that applied to her. On her joining forms, she said she was 49, no matter what the lines on her face might say.

After two years of hard labour in the awful conditions, she was rumbled. She was, in fact, 69.

In June 1944, the Echo reported that Mrs Dillon - then 70 - had been awarded the British Empire Medal "for services rendered to her country".

The paper noted: "For the two-and-a-half years she has been at a war factory, she has topped the attendance record, having lost only two shifts."

Very quickly after VE Day, operations at ROF 59 were scaled back, and by December 1945, it was empty. In August 1946, bulldozers took to the site, and then what buildings remained were converted into the Aycliffe Industrial Estate. Indeed, many of those survivors – and their attendant earthworks – can still be spotted, and the ROF 59 activity centre actively celebrates its links.

It did, though, take some time for the nation to celebrate the Aycliffe Angels. As non-militarised Home Front workers, they were not due any official commemoration, but in the 1990s, The Northern Echo began campaigning on their behalf. They were allowed to join Remembrance Day parades and their story was instrumental, and inspirational, in their local MP, Tony Blair, seeking ways to commemorate all Home Front workers. This culminated in 2005 with the Queen unveiling a monument in Whitehall to them.

l If you have any information on any Aycliffe Angel, we'd love to hear from you - particularly if you recognise one of the names of the people who were killed 75 years ago. Please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel