THE “sumptuous” chapel of the medieval Prince Bishops of Durham has been found nearly 400 years after it was blown up.

The discovery, announced this week, solves the great riddle of Auckland, and sheds amazing light on the national importance of this corner of County Durham.

It was always known that somewhere at Bishop Auckland, the prince bishops, who were the most important men in the kingdom after the king himself, had an impressive chapel, built around 1300 by the warrior-bishop, Antony Bek.

But it was destroyed during the English Civil War in the 1650s, but its size, appearance and location were forgotten, until archaeologists began digging beside Auckland Castle a couple of years ago, and gradually the enormity of the chapel emerged from the dirt.

“It was a slow realisation,” says John Castling, Archaeology and Social History Curator at the Auckland Project. “First we got the gateway and the towers but we didn’t realise they were a chapel. Then we found a supporting buttress and realised it was huge, and then we found the vaulting but it was so huge, so massive we thought could a chapel really be that big?

“It seems bizarre to think that this giant building has just gone. Now when people visit the castle, they remember St Peter’s Chapel but if you came here in 1400, you would remember Bek’s chapel.”

Bek became bishop in 1283. In 1298, he raised an army of 140 knights and 1,000 men to fight alongside Edward I at the Battle of Falkirk in which they defeated William “Braveheart” Wallace, leader of the rebellious Scots.

In 1306, Bek was made Patriach of Jerusalem and so became the senior cleric in Britain, and in 1308 he paid Galfrid, the Bailiff of Auckland, £148 for building his sumptuous chapel.

But when he already had a pretty magnificent cathedral at Durham why did he need such a chapel at Auckland?

“He was the king’s right hand man at Falkirk, and as the Patriach of Jerusalem, he is answerable to no one else but the Pope,” says Mr Castling, “but at Durham Cathedral, the Prior of Durham is in charge so he spends a lot of his episcopate arguing with the prior and monks.

“He wants to rule the North-East as an independent kingdom and the monks of Durham get in the way, so the chapel is all about his ambition to create a site that isn’t Durham where he can display his wealth and power.”

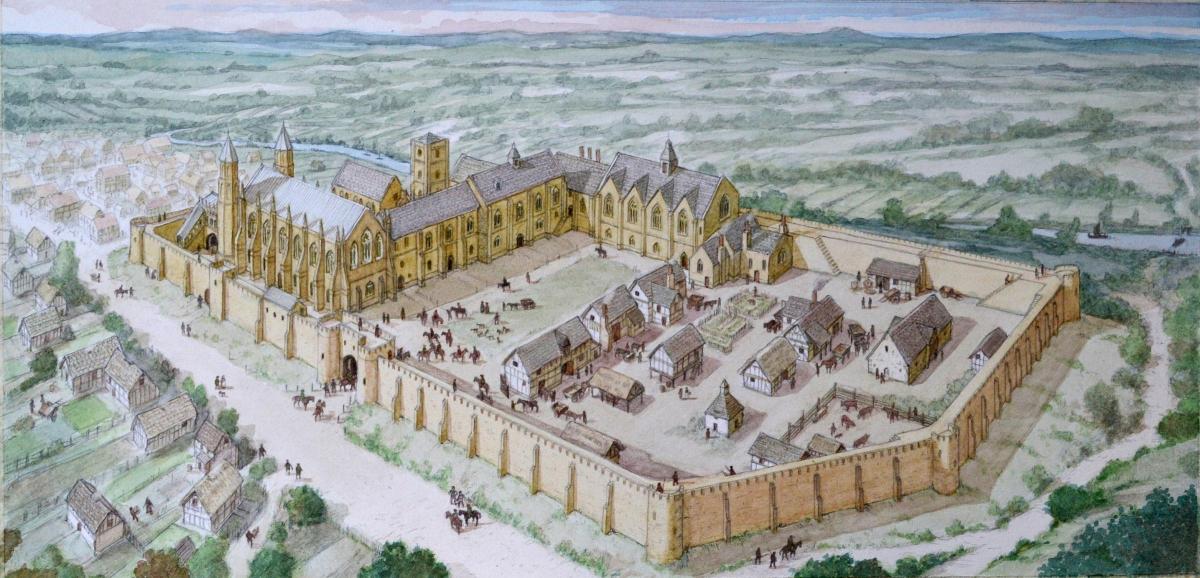

And so he created the largest private chapel in England – bigger even than the king’s in the Palace of Westminster, and is nearly as large as the king of France’s Sainte-Chapelle in Europe which was one of the wonders of the age.

Auckland’s chapel was 40 metres long and 12 metres wide and on two massive floors. It’s main entrance faced onto the market place and was a narthex – a courtyard porch popular in early Christian churches. On special days, ordinary people might be permitted to use the chapel on the ground floor, but the upstairs chapel was the preserve of the bishop only and his invited guests, with an ornate stone screen – pieces of which have been found – separating the chancel and the altar from the nave.

“It is early English Gothic in style but it is drawing inspiration from other places like cathedrals, ministers, abbeys in this country and on the continent,” says Mr Castling. “One detail we can’t think of anywhere else is the floor in the lower chapel which is a strange polished ash and lime mix which has been incised to make it look like polished marble: this concrete is what you get in continental churches.

“The upper chapel is far more elaborate, by permitted access only, and Bek had monks and priests saying mass there daily. It is possible there was a corridor or balcony from the bishop’s private quarters into the upper chapel – he could certainly lie in bed and hear mass, if he wanted.

“The ground floor is more cluttered. There are benches and seats around the outside and stone columns holding up the upper floor. It would feel much more intimate, darker, lit by candlelit – very atmospheric.”

The windows would have had stained glass in them, but not much has been found because it, and the lead that held it together, was very valuable and so would have been spirited away. One fragment, though, shows a self-sacrificing pelican plucking at its own breast, which was the symbol of Richard Foxe, who was bishop from 1494 to 1501, suggesting he paid for some repairs.

However, once Bek had completed the chapel as a statement of his power, it was largely unaltered for three centuries. It was the largest building in the town, and in the county it was probably only overshadowed by the cathedral and a couple of castles.

“It is still in use in the 1630s although the church tradition has changed: the bishops are now Protestant rather than Catholic,” says Mr Castling. “The top chapel is described as dainty but so echoey that a voice can hardly be heard – this was important in the new Protestant tradition in which sermons played a big part.”

But in 1642, the English Civil War broke out. It was a battle for power between the Parliamentarians and the Royalists which ended with Charles I losing his head in 1649. To the Parliamentarians, the Church of England was symbolic of the old Royalist power and also had to be broken down.

In 1647, Oliver Cromwell appointed Sir Arthur Haselrigg as Governor of Newcastle, and in 1650, he bought Auckland Castle for £6,102 8s 11d. Sir Arthur despised bishops, and so Bek’s enormous 350-year-old chapel appalled him.

He employed local Quaker John Longstaff to blow it up with gunpowder – scorch marks found on some stones support this story and dents in the floor perhaps show where the heavy vaulted ceiling came crashing down – and reuse the stone in a new mansion just inside the main gate.

However, this unhappy period lasted only till 1660 when Charles II was restored to the throne and the Bishop of Durham, in the form of John Cosin, was restored to Auckland Castle.

Cosin said that the castle had been “almost utterly destroyed by the ravenous sacrilege” of Haselrigg, who was thrown in the Tower of London, and in 1662, Longstaff was convicted in Durham of “demolition of the goodly chapel”.

Two years later, though, Cosin employed Longstaff to demolish Haselrigg’s mansion and to re-re-use the stone in converting the large banqueting hall into St Peter’s Chapel. In fact, so trusted did Longstaff become that he was allowed to brew the bishop’s ale.

But as St Peter’s was now the bishop’s impressive personal chapel, the remains of Bek’s chapel disappeared under vegetation and then, as the castle grew, other buildings went on top of it – by curious coincidence today’s Bishop of Durham has his office desk exactly beneath where Bek once had his altar in his upper floor chapel.

“Although this was the key piece of what the castle looked like in the medieval period, it was unknown, it was a void, it had been wiped from the face,” says Mr Castling.

“It is difficult to overstate how significant this building is, and finally discovering it was fantastic for the whole team, which included students from Durham University and volunteers from the Auckland Project.

“It is really important. It demonstrates just how significant the site is and that it is Bek’s favoured site where he’s building something of a national scale and importance. Auckland is not second favourite to Durham in his mind – it his primary residence. The chapel demonstrates the bishops as secular lords and Auckland is their northern seat.”

L An exhibition, Inside Story: Conserving Auckland Castle, which tells the story of the discovery of the chapel opens at the castle on March 4 and runs to September 6. It will feature some of the uncovered stonework and treasures, plus drawings of what this huge lost structure looked like.

Auckland Castle is open from 10am to 4pm, Wednesday to Sunday. Admission is £10 for adults, £8 for concessions, £3 for under 16s.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel