WHEN D350 was derailed, it toppled into a bog at Isaac Elders’ farm and started sinking, but for weeks afterwards, all south Durham dined on tomatoes rescued from its wrecked wagons.

Then, six days into the rescue operation, a burning US fighter jet crashed into a field a few hundred yards from the train wreck, blowing the unfortunate farmer Elders out of his tractor.

US Air Force investigators dashed to the scene, and despite their bus colliding with a car, found their pilot unharmed in the bog with his ejector seat and an inflatable dinghy.

They took him to hospital and tidied away their wreckage.

This left the railwaymen on the East Coast Main Line still munching their tomatoes and wondering how they could extricate D350, while the unfortunate Mr Elders, believing that troubles always come in threes, waited in trepidation for a third calamity to befall the area.

And the price of tomatoes in Newcastle soared.

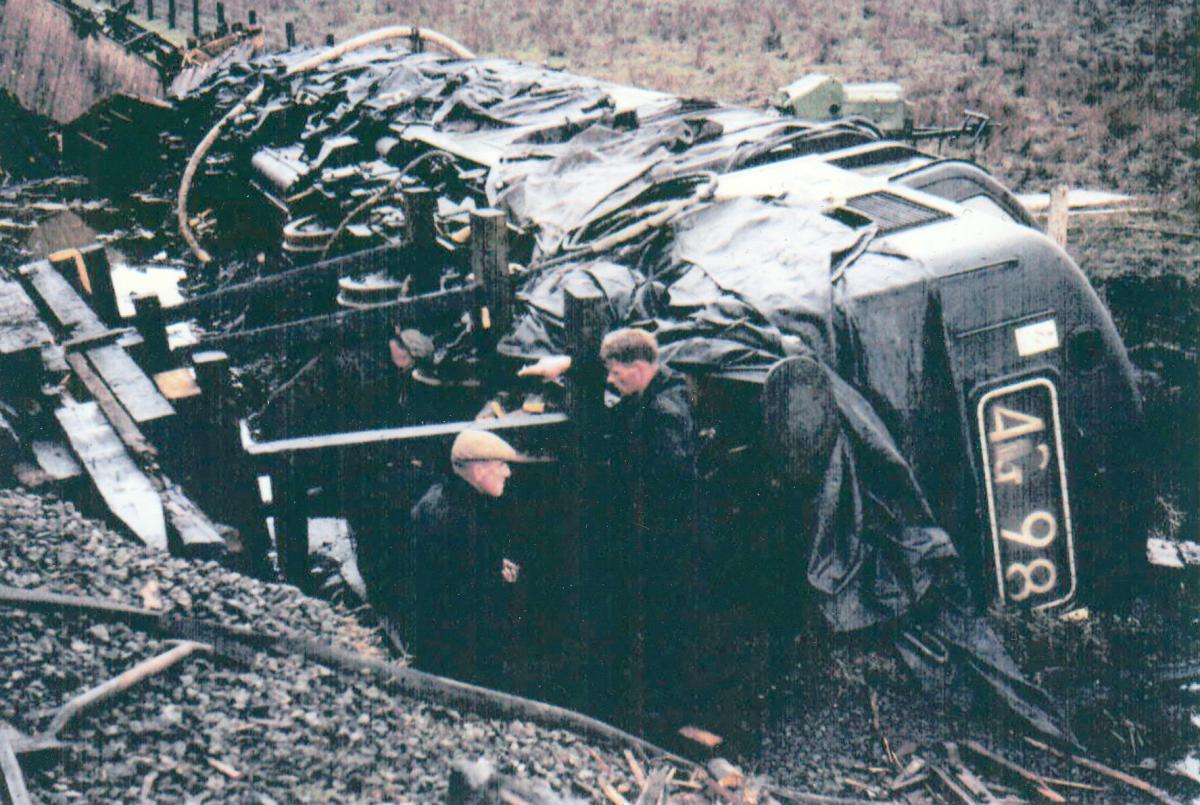

This, then, is the amazing story behind our mystery picture in Memories 355.

And, happy to relate, no one was harmed in the making of this story, although many tomatoes were terribly squished – one eyewitness recalls seeing a red pulpy porridge of them all churned up inside a wagon.

THE drama began in the early hours of Friday, May 7, 1965, when the signalman at Preston-le-Skerne, to the east of Newton Aycliffe, put D350 into a passing loop on the East Coast Main Line to allow the newspaper train behind it to get by.

D350 was pulling the 4G98 mixed goods train from York to Newcastle Newbridge Street. Among its cargo was a large quantity of tomatoes.

But its driver misread the signals and smashed through the points at the end of the loop, causing D350 to roll down the embankment and nosedive into the bog.

This is the Isles area of south Durham – named after the farms which are on slightly raised ground above boggy carrs. It was once a prehistoric lake, and little streams flow through the carrs into the Skerne. Railwaymen knew it as “the Ponderosa” because the watery land around the mainline wobbled when a fast train went through.

As D350 toppled, its train jack-knifed across the mainline. Minutes later the newspaper train – the 1N02 from Manchester to Newcastle pulled by D352, another English Electric Type 4 diesel loco – smashed into it.

The railway reacted quickly. In the dark, despite the isolated location of the crash site, bundles of newspapers were marched across the fields to a fleet of lorries which took them to Newcastle before dawn – morning newspapers, of course, are extremely important things.

But little could be done for D350. It was slowly sinking into the bog and could not easily be retrieved. It was left “half buried in gravel and water” until the necessary heavy haulage equipment could be assembled.

So the railwaymen who had been sent to drag it out turned their attention to the tomatoes.

“There were blokes there from all over south Durham,” remembers Mike Hogg, from Strensall in York. “We trekked across the fields carrying picks and shovels and found eight or 10 wagons on the floor which had sprayed the tomatoes everywhere.

“The gaffer said ‘help yourselves to tomatoes’. I didn’t because although my mother was a great cook she was absolutely hopeless with sandwiches and I knew all I would get was tomato sandwiches for weeks, but our gang vans were used as lorries to take the tomatoes round to people’s houses.”

Trevor Horner, was 17 at the time and tells a similar story. He was a junior technical assistant in the district engineer’s office and at the start of a lifelong railway career – he is still a volunteer on the Weardale Railway.

“The site access was through the farms and when we arrived, people were pushing rail bogies, or trolleys, loaded mounds high with tomatoes,” he says. “The loss adjustor had been and had written everything off so it was all scrap.

“My boss said ‘get in that box car and get as many tomatoes as you can’. I had to perch on the side of this wagon and literally rolled my sleeves up and was pulling whole tomatoes out of this porridge of smashed tomatoes – I must have got 20 or 30 boxes out. They were taken back to the office and shared out.

“My share went to my aunt who ran the VG shop at the top of Redworth Road in Shildon. She paid me trade price, so I got a bit of pocket money, and the tomatoes were washed off and sold.”

While south Durham was flooded with a glut of liberated tomatoes, in Newcastle there was such a tomato shortage that the price shot up by 50 per cent.

Back at the crash site, railwaymen covered the £100,000 loco with a tarpaulin and began preparations for the rescue. They dammed a stream and pumped out water to make the ground stable. They burrowed beneath the loco so steel hausers could be tied around it.

Then, on Thursday, May 12, a £300,000 USAF Super Sabre jet crashed two fields away. It was so close they could feel the blast.

Captain Marshall M Kroot had been flying back to RAF Lakenheath in East Anglia when black smoke began billowing from his engine. He maydayed the newly civilian Teesside Airport, at Middleton St George, but then spotted the empty carrs below and decided to ditch, pressing the eject button as the plane plummeted.

Isaac Elders, of Swan Carr Farm, saw it coming so close to him that he threw himself out of his tractor in fright, causing the vehicle to run off into a hedge bottom.

His wife, Muriel, saw the plane bounce across the field. "It was a terrifying sound, and there were bangs and cracks all over as bullets exploded, " she told The Northern Echo. "Everything seemed to be going like a whirlwind. There was fire everywhere."

The explosion brought down power lines, cutting off the supply to the railway signals, so once again, the East Coast Main Line ground to a halt.

Happily, Capt Kroot was practically unscathed. He was discovered nearby with his parachute, his ejector seat, a fully-inflated emergency dinghy, some maps and ration tins, and a sore shoulder.

A US Air Force investigation team immediately flew from Lakenheath to Leeming to collect him. The Northern Echo reported: “During the journey from Leeming with a police car escort, their bus was involved in collision with another car and although no one was hurt, it delayed the start of the investigation.” Perhaps this was the hat-trick of mishaps that Mr Elders was said to be fearing.

Once the Americans had taken their plane away and power had been restored to the mainline, the railwaymen were able to set Sunday, May 23, as the date to shut the mainline once more and extricate D350. They brought two 75 ton cranes, one from Gateshead and the other from York, to the scene, and began lifting at 4am.

The hausers were wrapped around the stricken 133 ton loco, and the cranes pulled it upright. It was then detached from its bogies – the heavy wheels – and the Gateshead crane lifted the top half of the loco up.

It was left dangling in mid-air while the York crane tried to lift the wheels from the mud. After nearly 12 hours, the bogies came free with an “almighty squelch” and the crane lifted them onto the track. The Gateshead crane lowered the top half back onto its wheels and at 4pm, D350 gingerly was pushed back to Darlington.

It was scrubbed down and repaired, and the engine which had hauled the troubled tomato train worked on for another 20 years.

“THE derailment occurred on Preston loop which, in the direction of travel, curved to the left,” explains Mike Hogg. “For about the first quarter of the length of the loop, the only signal you could see was the Main Line one as the loop signal north only becomes visible when you are about three-quarters of the way along.

“I was told the driver saw the Main Line signal off and took it to be the loop signal. When he got closer, he realised his mistake and put on the brakes but the weight of the train pushed him over the catch points and into the bog.”

WITH thanks to eyewitnesses Mike and Trevor, and to other contributors: Richard Barber, Mike Barnard, Geoff Gregg, John Heslop, David Sayer, Ian Gray and John Askwith. If you’ve got anything to add, we’d love to hear from you: chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk. Please see over for the front page report of the derailment in the Echo’s sensationalist evening sister paper, the Northern Despatch.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here