EXACTLY 450 years ago last week, things were hotting up in Barnard Castle. The Protestant royalists were holed up in the castle, besieged by a ragtag army of 5,000 Catholics and their local noble leaders.

This was, as we’ve told in recent weeks, the Rising of the North, the biggest challenge that Queen Elizabeth I faced in her 45 year reign.

The Teesdale town was very much the centre of the rebellion, and to this day it has a remarkable reminder of what happened.

A remarkably wrong reminder…

Sir George Bowes, whose principal home was at Streatlam Castle on the road between Barney and Staindrop, was loyal to the queen and her Protestant faith. His neighbour, Charles Neville, the Earl of Westmoreland who lived in Raby Castle, was not.

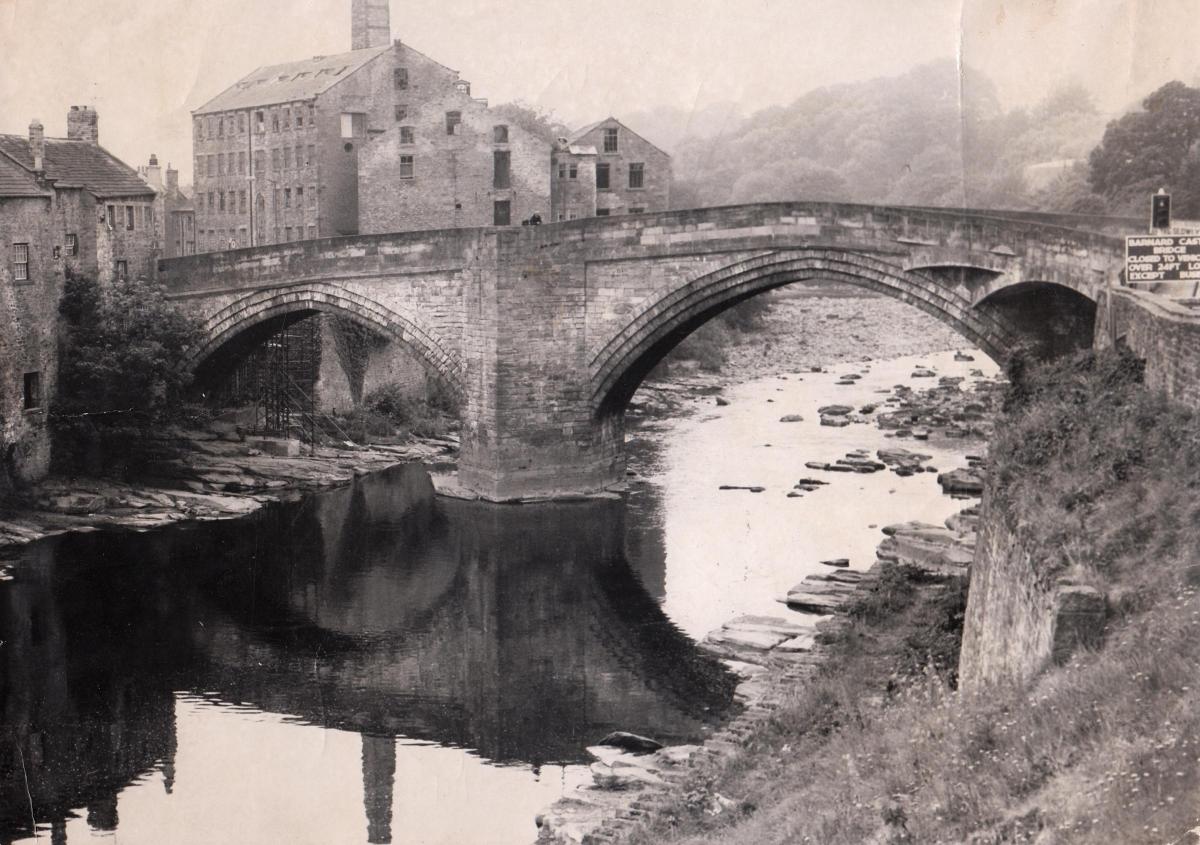

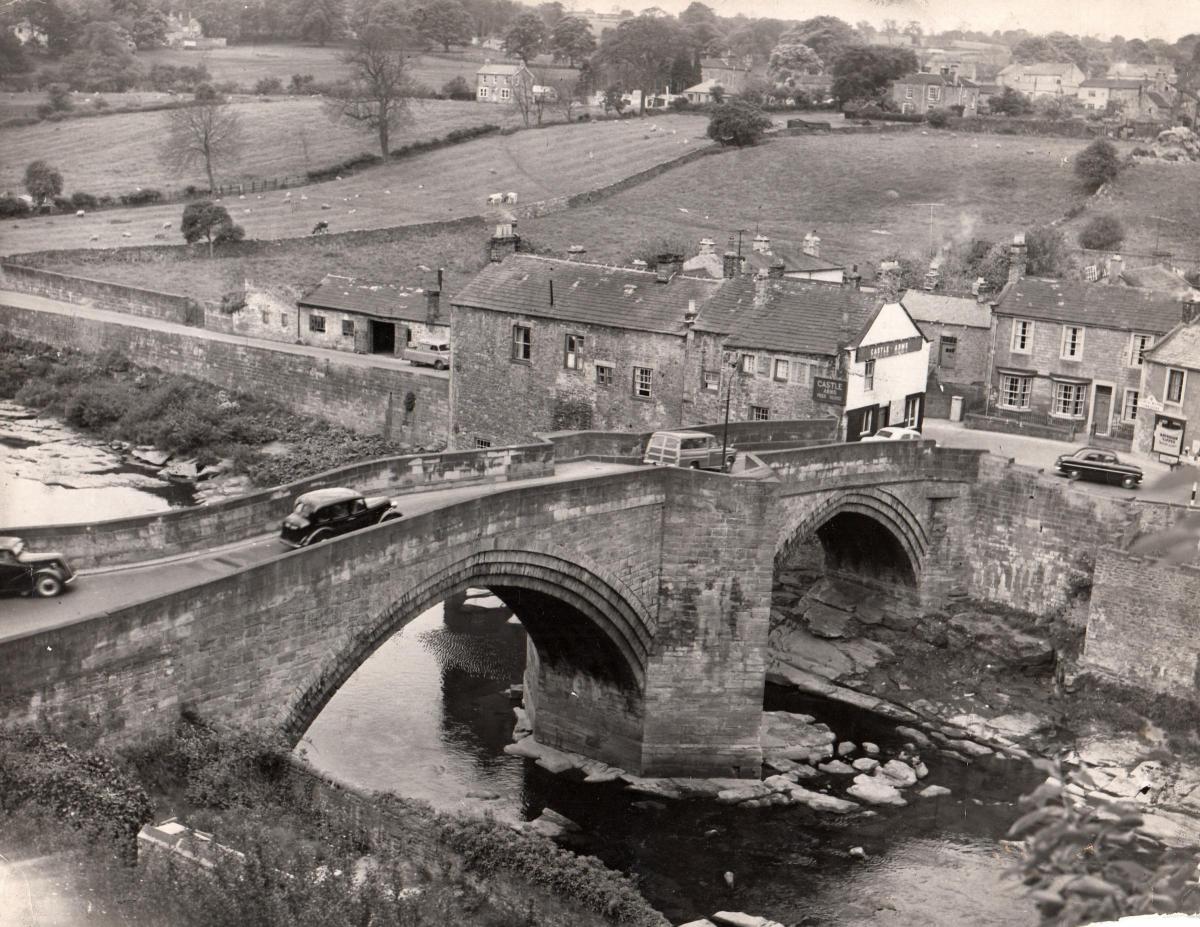

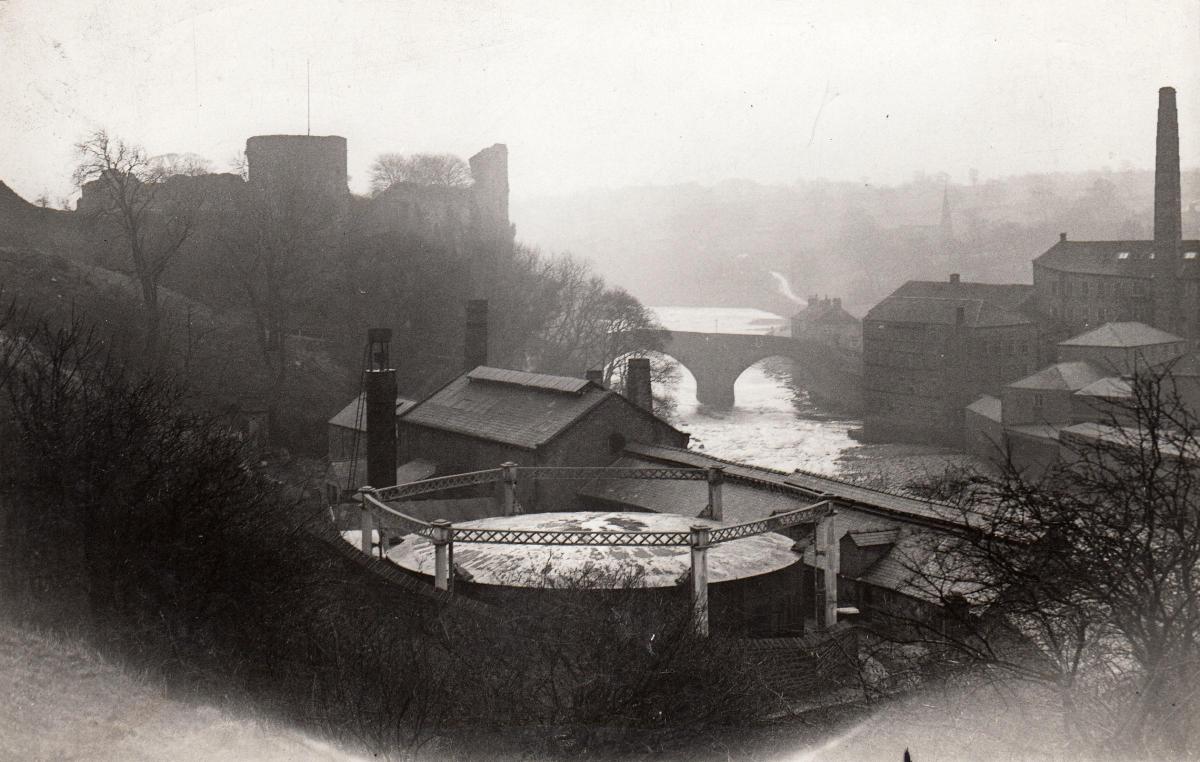

In November 1569, Sir George became so worried by his neighbour’s bellicose behaviour that he left Streatlam and locked himself and his followers inside the castle at Barnard Castle. It was built in 1112 by Bernard de Baliol – it is Bernard’s castle – on a dramatic stronghold 80ft above the Tees with the County Bridge down below.

On December 2, Westmoreland, having captured most of south Durham, arrived with his army and surrounded the castle. Because the castle was impregnable, he decided to wait for Sir George to surrender. Westmoreland had all the advantages: more men, food, water and superior weaponry – Sir George only had four slings and one cast iron cannon.

Westmoreland also had a very bad poet on his side, who came up with an appalling ditty with which to taunt the besieged and beleaguered Sir George:

“A coward, a coward of Barney Castle

Daren't come out to fight a battle.”

Sir George's men couldn't take this taunting, and desperately tried to jump off the castle walls to escape. Sir George wrote: "In one daye and nyght, 226 men leapyd over the walles, and opened the gaytes, and went to the enemy; off which nomber, 35 broke their necks, legges or arms in the leaping."

Those that survived told Westmoreland of the secret underground water supply that was keeping Sir George sustained. The supply was cut, and on December 14, Sir George surrendered.

But because the two noblemen had been quite friendly when they lived in their neighbouring castles, Westmoreland didn't kill Sir George but allowed him to walk free. Sir George dashed off, joined the 12,000-strong queen’s army, which crushed the rebellion, forcing Westmoreland to flee to France, and never again was he able to come home to Teesdale.

In the hurly burly of the siege, the County Bridge got broken.

This had been a crucial crossing point for centuries. The Romans had marched this way from Lavatrae (Bowes) to Vinovium (Binchester) although they had probably splashed their way across – the village of Startforth on the Yorkshire bank gets its name from the “street ford” that was there.

But when travel writer John Leland passed through Teesdale in the late 1530s, he was able to note that “the castelle of Barnard stondith stately apon Tese” and he was able to cross the river “on the right fair bridge of 3 arches”.

Then came 1569 and all that, and the three arches were so badly damaged during the siege that the bridge had to be rebuilt. The new crossing had only two arches, but in the pedestrian refuge in the centre of the bridge’s south side, the stonemason carved the date “1569” and added letters to indicate that this was the county boundary between Durham and Yorkshire.

It was also the boundary between the dioceses of Durham and Chester, and somehow in the northern refuge the mason managed to squeeze a tiny chapel.

In the early 17th Century, Cuthbert Hilton took up residence in the chapel. His father was the Reverend Alexander Hilton, the curate of Denton, who had taught him the Bible, but Cuthbert had no formal clerical qualifications. Nevertheless, a couple determined to quickly get married, perhaps despite parental disapproval, would pay him half-a-crown and he would lay his broom along the boundary line across the centre of the bridge.

Then the couple would jump over the broom and when they were in mid-air – when they were neither under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Durham nor that of the Bishop of Chester – he would pronounce them man and wife.

And he, too, would repeat a little ditty:

“My blessings on your pates,

And your groats in my purse

You are never the better

And I am never the worse.”

And you, of course, would go on to live over the brush.

On November 15, 1771, the district was overwhelmed by the greatest flood of all time. The Tees rose above the western arch of the County Bridge, sweeping away the stonework so the cobbler who lived in the "chapel" in the centre had to lay a ladder over the void to reach Yorkshire.

In the mill – latterly the White Swan Inn – on the Startforth side of the bridge, a weaver was forced to abandon his apparatus in his lower rooms and fled to his attic. When the waters retreated, he retrieved the textile that he had left in his dye-kettle, and found it had taken on a stunningly vibrant colour.

The London buyers were astounded by it and placed repeat orders, but the weaver "not being assisted by the genius of the river, failed in every attempt" to replicate the colours.

The bridge was repaired once more, and it was strengthened at the Durham end by the addition of "squinch" arches – arches that provide a distinctive, diagonal support.

Towards the end of the 19th Century, the dates and the lettering on the stone in the central refuge had weathered to the point of illegibility – today, there is nothing to see except NYR in metal on the Startforth side.

So a stonemason repairing the riverside approach to the bridge decided that the date was too important to be lost. He chipped out a new stone, added “ER” to it to give it that Elizabethan ring of authenticity, and then carved on the date of the Rising of the North. He knew off the top of his head that it was 15-something or other with a six and a nine in it.

But he got it the wrong way around, and so the stone says “1596” when the Rising took place in 1569. Perhaps that’s why it is tucked away beside a lamp-post as an attempt to conceal the mistake.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel