“THE new bridge at Saltburn-by-the-Sea, which spans the well-known Skelton beck glen, is within a day or two of completion,” reported The Northern Echo’s sister paper, the Darlington & Stockton Times, on August 14, 1869.

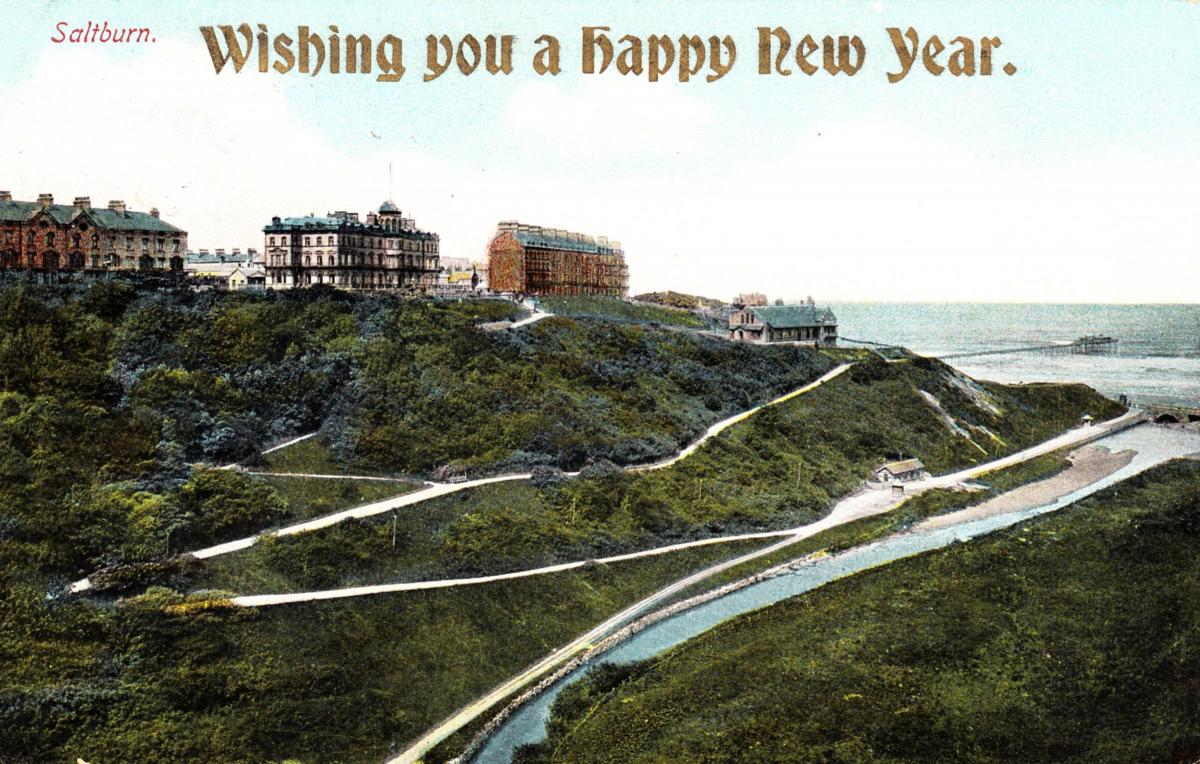

And so, 150 years ago this month, one of North Yorkshire’s most remarkable high-level tourist attractions, offering amazing views of coast and countryside, came into operation.

It’s opening, though, was about four months behind schedule because three workmen had been killed during its construction. This tragedy may explain why the bridge, which lasted until 1974, slipped into usage without any great ceremony.

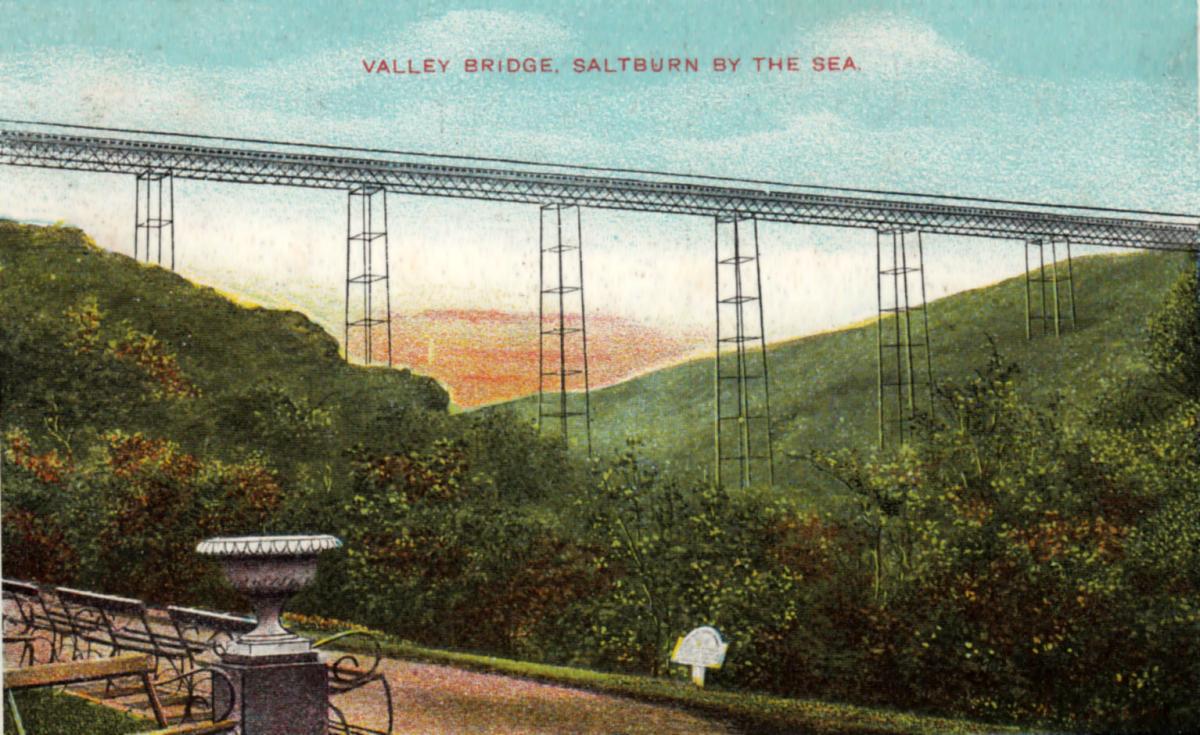

The D&S Times in the summer of 1869 described the bridge to its readers: “The whole of the ponderous girders, 85ft in length, are now fixed and the roadway laid. The bridge is 800ft in length, there being seven spans and eight cast-iron piers; the highest point is 160ft and the width is 25ft.

“A small toll is to be levied for passengers using the bridge.”

It was this small toll that give the bridge its popular name: the Ha’penny bridge.

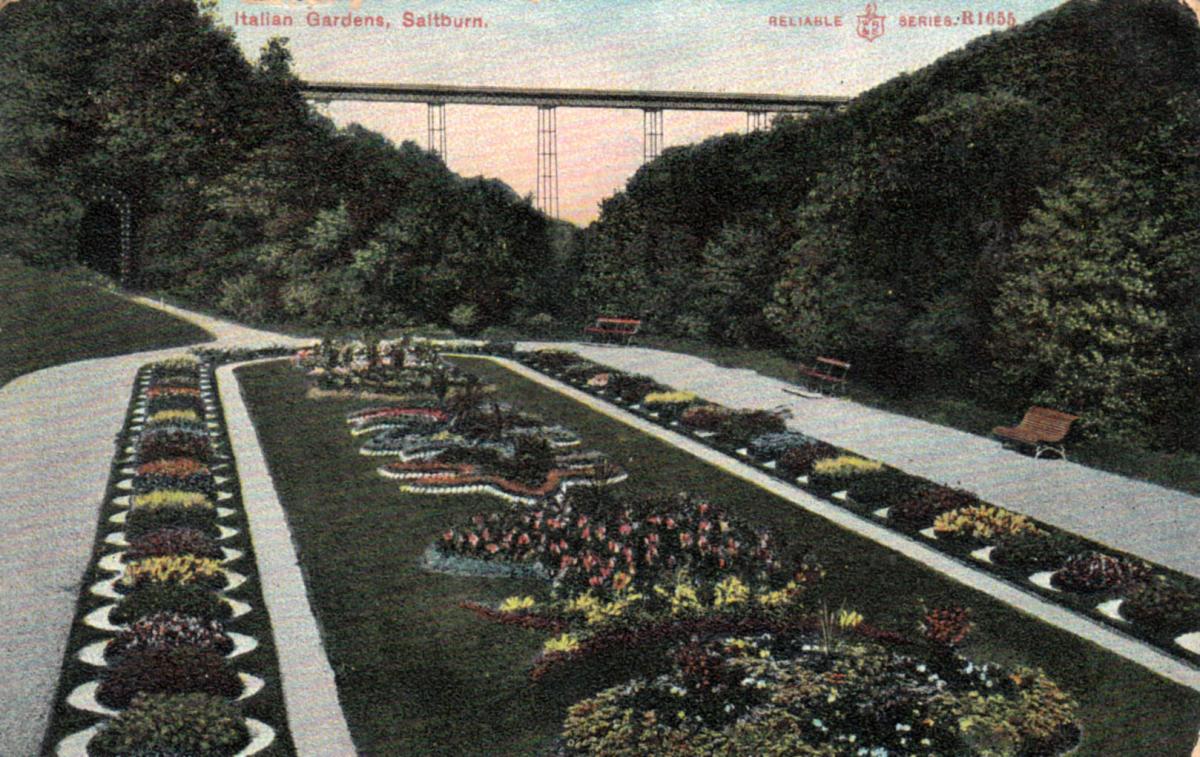

The bridge spanned the deep glen which had been one of the attractive features identified by the Darlington railway entrepreneur, Henry Pease, when he decided to develop the railway seaside resort at Saltburn in the early 1860s. His thinking was that if daytrippers were blown off the beach by a tempest they could at least seek sanctuary amid the glen’s steep sides and in the ornate Italianate Valley Gardens.

The bridge over the glen, though, was the brainchild of John Thomas Wharton, of Skelton Castle, who owned land on the east side of the glen, opposite Mr Pease’s resort on the west side. Mr Wharton hoped that by building a narrow carriagebridge over the ravine, he would be able to open up his estate to development. It didn’t work. The only buildings on the east side would be the tollkeeper’s cottage and a mansion, Cliffden, which is now a little housing estate.

The bridge was built by the Middlesbrough firm of Hopkins, Gilkes and Company and – slender and spectacular – it looks very similar to the iron trestle bridges of Belah and Deepdale that the company had built on Mr Pease’s railway line over Stainmore.

The bridge’s foundation stone had been laid in early September 1868 by the project engineer, Mr Wilman, who confidently predicted it would be open in time for the 1869 tourist season. However, on April 7, a girder fell 130ft from the top of the bridge. It bounced and crashed into the central column, causing it to collapse.

In a split second, one of the three workmen on the column decided his best chance of survival was to jump. He died, struck by a girder, before he hit the ground.

“The other two men remained, but one of them was also killed instantaneously, and the other man died in a few minutes,” the D&S had reported back in April that year. “The bodies of the men were a sad, mangled sight, one man having his head literally smashed to atoms, and the man who breathed a few minutes had both his legs broken.”

The Leeds Mercury reported that the poor fellow “had to be literally ‘jacked’ out from underneath the debris”.

The fatalities were foreman James Denny, of Middlesbrough, and George Simpson and James Miles, both of Marske.

So in late summer 1869, the bridge was belatedly ready for opening. It was strong and wide enough to take horsedrawn carriages (toll: 6d), and even early motorcars though they were banned when a new-fangled internal combustion engine spooked a horse, which nearly threw its rider over the parapet.

The bridge could have a unique place in telephone history as in 1877 young mining engineer Francis Fox stretched a wire across it from his home in Balmoral Terrace to Cliffden and spoke a few words. Francis, who was later knighted for his work extending the London Underground and digging the Mersey Railway Tunnel, claimed that this was the first telephone call in Britain.

In the mid 20th Century, Cliffden became a school, and pupils crossed the bridge twice a day to get to classes. “Initially, the toll-keeper collected the coins every morning,” says Peter Sotheran of Redcar, who was a pupil there in 1956 and 1957. “Later the school made an arrangement on behalf of the pupils and paid a lump sum each month or school term.”

By then, the bridge was beginning to look its age. “During 1956, repairs were carried out to the decking,” says Peter. “This entailed removing the areas of the road surface and sections of the timbers that supported it. The holes were protected by nothing more than a few rough timbers, and there was nothing to stop us from peering over the edge, as 12 year old boys are wont to do, and gazing at 130 feet of fresh air between us and the ground below.

“Sections of the elegant railings that ran along the sides of the bridge were also removed at the same time and ropes stretched across the gaps to keep people safe.”

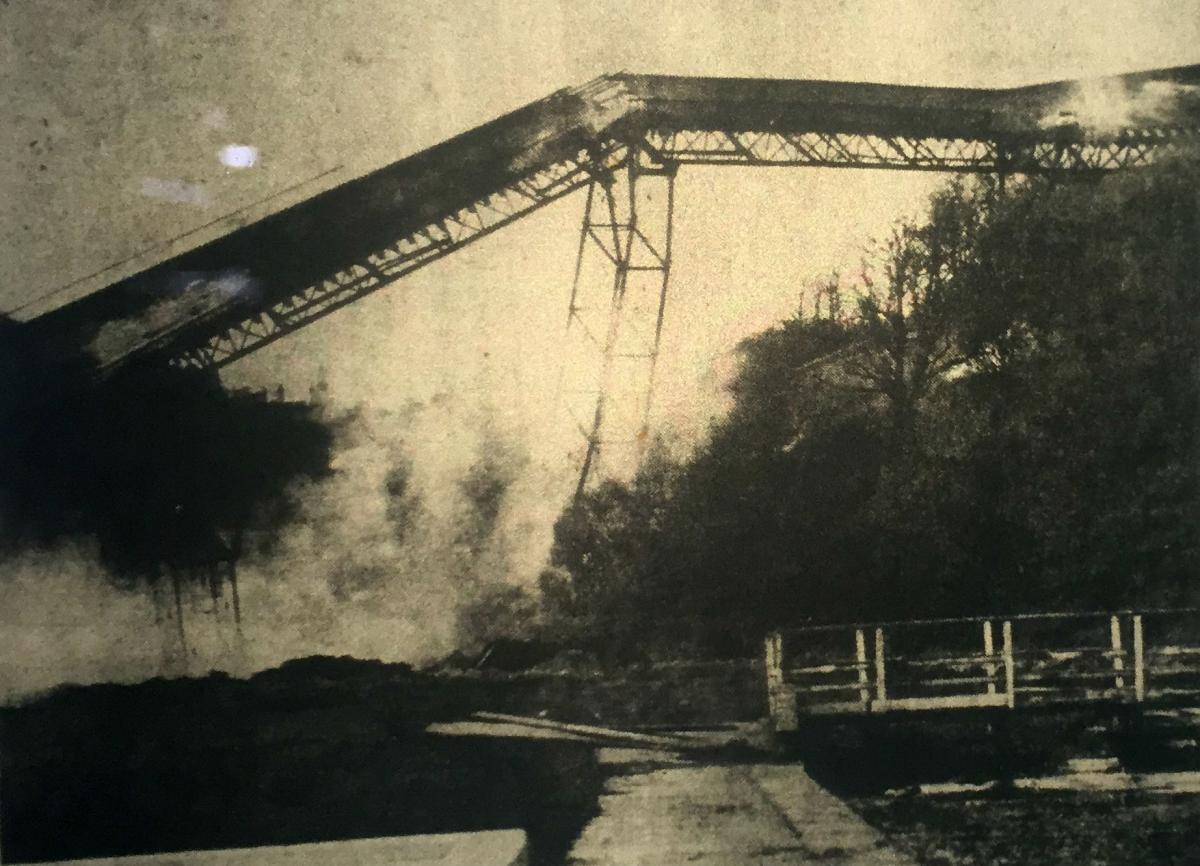

Despite these repairs, the bridge became increasingly unsafe. Some people fought for it to be repaired, but it was demolished on December 17, 1974, when 6lbs of gelignite was strapped to each of its seven legs and detonated at half-second intervals.

“I recall it sagging from one end to the other, rather like a camel sinking to its knees,” says Peter, who witnessed the explosions.

The demolition cost £50,000 (about £450,000 in today’s values) whereas the construction cost in 1869 had been only £7,000 (about £73,000 today).

For 105 years, crossing the high level Ha’penny Bridge was a major part of the Saltburn experience, but now even the octagonal tollkeeper’s cottage on the west side has gone, replaced by a bandstand on the edge of the glen.

One sad statistic survives: during the bridge’s lifespan, 79 people committed suicide by jumping from it. Only one person survived the 130ft plunge and she, it is said, was a lady whose large skirt parachuted her to safety. However, we have been contacted by someone who says that in the late 1950s, a well known Saltburn personality, Madge Prince, jumped from the bridge after a row with her husband. Fortunately, she got caught in the trees, suffered a few broken bones, and was able to rebuild her life in Redcar.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel