TWO thousand Irishmen swathed in emerald green followed the coffin, draped in a “gorgeous pall trimmed with green and yellow silk”, as it made its way down Darlington’s Northgate towards the police station.

Inside lay the broken body of Owen O’Hanlon whom the Irishmen believed had been beaten to death by a policeman.

Six abreast, they carried him silently on their shoulders with, behind them, 12 mourning carriages crammed with his family and friends, followed by an “immense concourse” of ironworkers from the town’s Albert Hill district.

“A fearful groan broke forth from the procession as the head of it halted opposite the police station,” said The Northern Echo, of October 14, 1872, “and the roar of angry execration was repeated all along the long line of the crowd up to its extremity, which was at the time near Westbrook.

“From some of the windows of the mourning coaches hands were stretched, and angry expressions were heard, and one shrill voice, presumably that of O’Hanlon’s mother, cried out: “Ye murderers, you have killed my son!”.”

O’Hanlon, said the Echo, was the Fenian leader in the town. The Fenians were at war with the British government, fighting to expel the British army from Ireland so that it could be free.

Three years earlier (as Memories 411 and 415 told), O’Hanlon had purchased the bullet which “Gentleman” John McConville had used to kill fellow Irishman Philip Trainer at point blank range outside the Allan Arms on the Hill. O’Hanlon had escaped prosecution, but McConville – who had previously been arrested fighting against the British in County Cork – had been hanged at Durham jail for the murder.

Shortly afterwards, though, O’Hanlon, 28, had been convicted of firing a pistol at a policeman on the Hill, which home to a large population of Irish ironworkers. By the mid-1870s, there were 3,500 ironworkers employed on the Hill, many of them migrants, and many of them employed at William Barningham’s works, which were the biggest in the north.

For the shooting, O’Hanlon had been jailed for a year. After his release, he had returned to the Hill, but had been unable to regain employment at Barningham’s so he lived with his parents, Bridget and Philip, in Ayton Crescent, beside the East Coast Main Line.

Indeed, it was said that things had got so hot for him – the police would obviously want to keep an eye on a man convicted of shooting at them – that the Irish community had collected money to enable him to disappear to America. They’d collected more than enough to pay for his passage, and it was said that he wanted to take the excess in cash whereas the other Irishmen, perhaps not trusting him to depart, said they’d send it when he arrived.

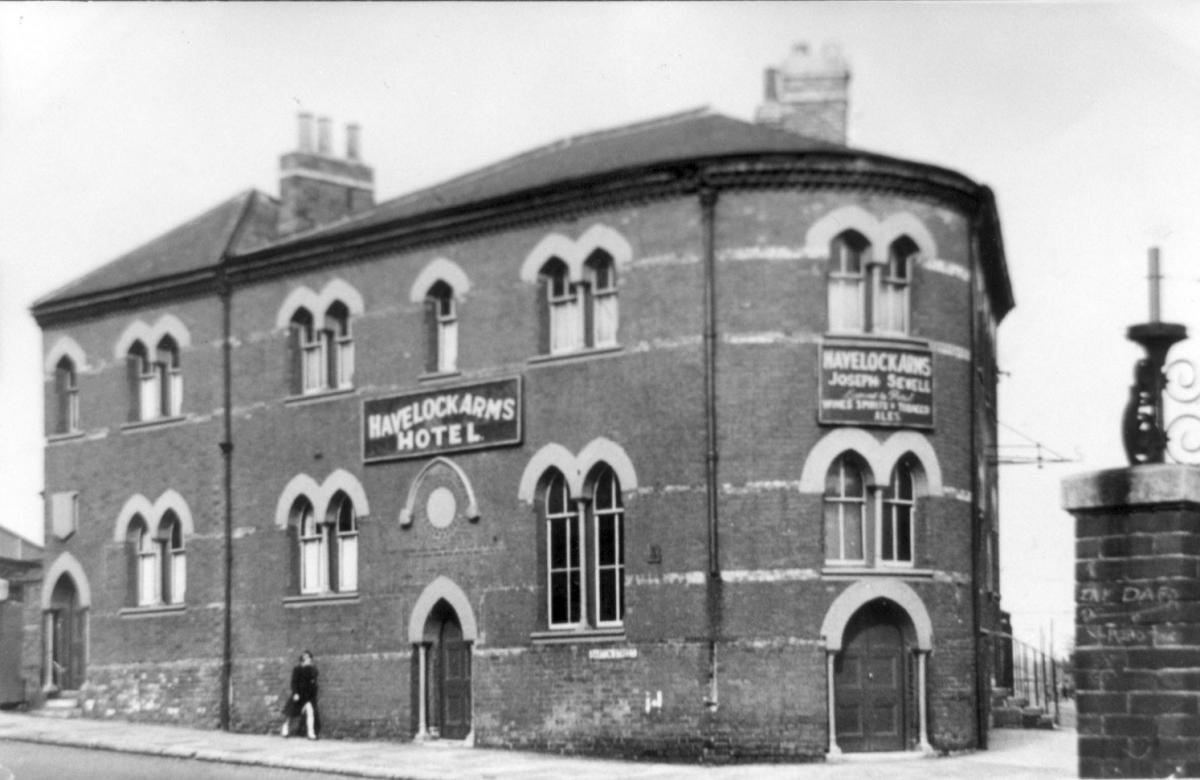

On October 1, 1872, the dispute boiled over into a prize fight on a grass field beside the Havelock Arms on Haughton Road and opposite the newly erected Primitive Methodist Chapel: O’Hanlon, striped to his shirt sleeves, versus John Sweeney, of Barton Street, striped to the skin with his seconds strapping belts around his waist.

Despite 40 or 50 people being present, what happened was fiercely contested in court. Sweeney, and his followers, said it was a good-natured 10-minute wrestle over a girl which ended without any blood being spilt and O’Hanlon vaulting over a fence to shake Sweeney’s hand.

Other neutral eyewitnesses, like the miller from Haughton, saw a brutal 45-minute beating in which Sweeney repeatedly shook a drunken O’Hanlon, punched him in the face and banged his head on the ground. Bloodied and dazed, they said O’Hanlon fell against a fence as he uncoordinatedly tried to have another go at his enemy.

The two policemen who dashed over from Northgate, Sgt Richard Cuthbert and PC Watson, found O’Hanlon drunkenly staggering semi-naked around Haughton Road, and they marched him off to the cells. O’Hanlon, who was known to Sgt Cuthbert, said he would come quietly, but when they passed under the old Stockton & Darlington Railway bridge, he pushed PC Watson into a ditch and ran off.

What happened next was again fiercely contested. Sgt Cuthbert said that O’Hanlon was so drunk and exhausted after the fight that he easily brought him to a halt and gently rolled him over his knee to the ground. He picked him up and locked him up in cell eight at the Chesnut Street police station to sober up.

Next morning, O’Hanlon’s mother, Bridget, found her boy covered in vomit in the cell with a nasty gash on the back of his head. She told him: “Your friend, the sergeant, has finished you this time.” She called Dr James Easby, who cleaned the wound, but found that O’Hanlon was still badly intoxicated.

On October 3, O’Hanlon’s condition was deteriorating so the head of Darlington police, Superintendent Rogers, allowed him to go home. Doctors regularly visited him, but he died at his parents’ house on October 10. Bridget said his last words to her were: “Mother, if I die, it’s the police that did it.” And Philip, his dad, said the last words to him were: “Father, father, father, they’ll murder us all.”

The funeral on October 12 attracted Fenians from all over the North-East, who, in a display of strength and passion, blamed the police outside their station in Northgate.

On October 18, the inquest into O’Hanlon’s death opened in the Allan Arms on the Hill – the scene of the 1869 murder. The pub had a room large enough to accommodate the coroner, Thomas Dean, the 19-man jury, various solicitors, policemen, doctors, witnesses and a big crowd of excitable Hill residents.

By now, Sweeney was in custody – although no one knew what charge he was facing. Supt Rogers told the coroner the police had received information of a Fenian plot to rescue the accused and so Darlington’s constables ringed the pub.

The big issue was how O’Hanlon came by the wound on the back of the head, which doctors agreed had led to fatal bleeding on the brain.

Sweeney’s case was well conducted by William Brignall, a Durham solicitor who often acted against the police. He enticed Dr Easby into saying: “I will undertake to say that a policeman’s baton is likely to cause such a wound on the head. Such an instrument would be more likely to cause it than a man’s fist.”

Then he got another well known local surgeon, Dr James Howison, to examine Sweeney’s “fleshy” hands. Dr Howison said they bore no signs of a brutal brawl, and added: “Sweeney’s hand, open or clenched, would not produce such a wound as existed on the back of deceased’s head. A policeman’s baton would be likely to produce such a wound.”

But the doctors also agreed that the wound could have been caused by a desperately drunk man rolling off a cell bench in his sleep and smashing his head against the toilet.

Then Mr Brignall produced two key witnesses. Firstly, John Johnson, who claimed to have been on the Hill for only six weeks. He said he had watched from outside the Havelock Arms as O’Hanlon had broken free from the policemen taking him away. He said that he saw the stripes on Sgt Cuthbert’s uniform as he lifted his truncheon and he said: “I saw a staff in Sgt Cuthbert’s right hand with his arm upraised, but I did not see him use it.”

Then a boy, George Fairless, aged 11 or 12, took the stand. He had been returning from the town centre with Mary Ann Christer when O’Hanlon had dashed in front of them. Mrs Christer had only seen a melee, but George said: “The sergeant put his hand to the back of his back and pulled something out of his pocket with a piece of string tied to it, and he hit O’Hanlon on the back of the head with it (applause). It was a piece of wood, thick at one end but smaller at the other where he took hold of it. Then O’Hanlon staggered back and fell on his right side when the other policeman kicked him.”

The boy added: “The blow made a rattle when it was delivered.”

Over the course of four weeks, George stuck to his story, even though Sgt Cuthbert swore he had dashed to the scene of the fight so quickly that he had not taken his truncheon with him and even though his colleagues swore they had seen it hanging on its usual nail in the station.

Summing up, Coroner Dean concentrated on the cause of the wound. “Was it the violent shaking of the deceased by Sweeney whilst deceased was in a drunken state?” he asked. “I think the evidence will not bear that out. Was it by a blow from a policeman’s truncheon? The evidence on that point is not sufficient. Lastly, was it caused by the deceased accidentally falling in the cell? That is certainly a very ingenious suggestion, it is not sufficiently supported by evidence.”

The 18 jurymen – whose chairman was an ex-policeman who had received lurid death threats during the hearing – retired for four hours and were heard rowing among themselves. When they came back into the pub at gone 7pm on November 21, they had failed to reach a verdict.

Coroner Dean thanked them for their efforts and discharged them while setting Sweeney free.

The Echo concluded its lengthy coverage by saying: “It is very improbable that another jury will be empanelled as it would necessitate the exhumation of the body of the deceased. So ends the great case which has claimed so much public attention for some time past.”

However, the hot-shot Durham solicitor was not going to let it lie. He was gunning for Sgt Cuthbert…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here