Letter to the editor, November 25, 1918

I desire, through the medium of the Press, to urge all ministers of religion that with the object of preventing the spread of infection, it is most important that at the funerals of persons who have died of influenza, that the coffin should not be taken into the buildings but should be left in the open air during the service. This procedure is usually followed in the cases of funerals of persons who have died from the more common infectious diseases such as smallpox, scarlet fever and diphtheria and ought undoubtedly to be followed in the case of influenza.

Yours truly, T Eustace Hill, County Medical Officer of Health, Durham

ARMISTICE Day must have been greeted with relief as well as joy by Mary Farrow and her husband, Charles.

They had both witnessed the horrors of war and experienced the pain of loss, but when the guns at last fell silent 100 years ago, they must have hoped for a better future and a peaceful life together with their new baby.

When peace was declared, Charles, 28, a second lieutenant serving in northern France with the Royal Field Artillery, was granted 14 days home leave and he dashed home to the North-East to celebrate with Mary, 25, and their nine-month-old daughter, Carol.

But tragically, as a recently restored white cross in Gainford churchyard shows, there was to be no better future or peaceful life for either of them. Within three weeks of the armistice, they would both be dead, killed not by enemy guns but by the Spanish flu that swept around the globe and killed more people than the war itself.

The pandemic is now believed to have started in early 1918 in Kansas, in the US, when bird flu in waterfowl passed to farmed chickens and then to their human handlers. This was a virulent virus and local doctors noted its capability to kill – it was also a cunning virus that was able to capitalise on the conditions of the time.

In early 1918, America, which had declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, was gathering hundreds of thousands of men in training camps and then shipping them on huge liners to the European Western Front.

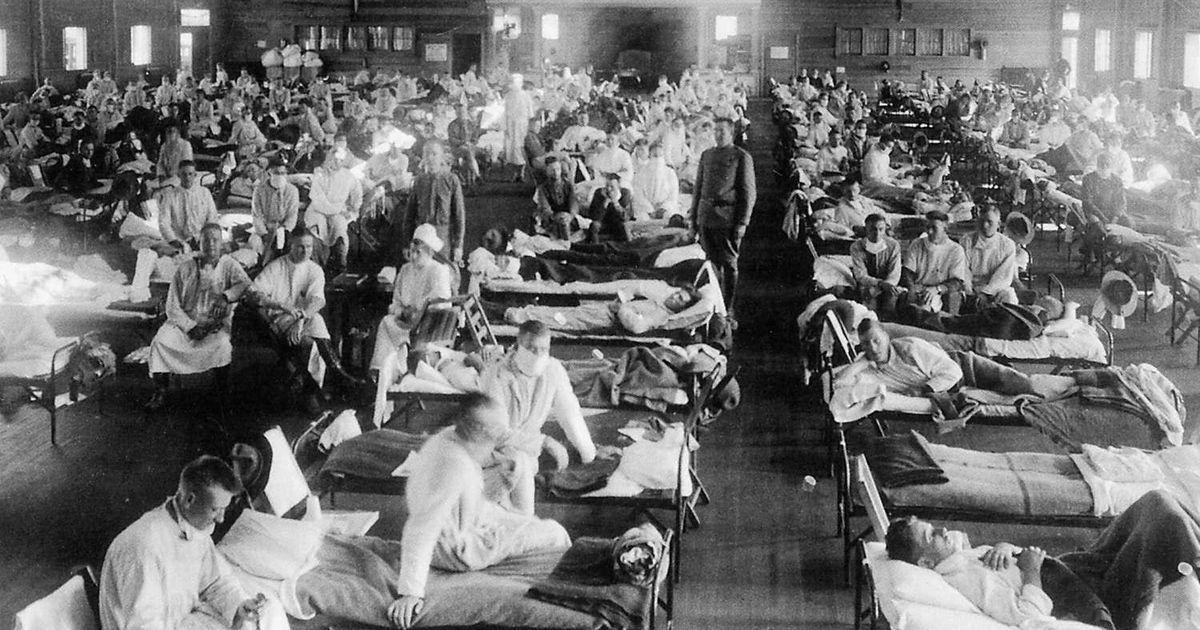

On the morning of March 11, in one of those camps, Camp Funston in Kansas, company cook Albert Mitchell reported to the infirmary with flu-like symptoms.

By lunchtime, 102 soldiers in the camp had joined him.

By early April, with up to 10,000 US soldiers a day arriving in France, the virus was in the trenches. The sick were shipped home to Britain, allowing the virus to spread along the railway networks so that by June, 100,000 people were infected in Manchester.

However, to keep the machinery of war turning, the British government needed the munitions factories to stay open, the railways to keep running, the postal system to keep delivering. The word was to “carry on”, and reports of an epidemic were played down.

But it was a global condition. At the end of May, Alfonso XIII, king of the neutral Spain, fell seriously ill, as did his prime minister and members of the cabinet, and the disease caused businesses and banks to shut down. The Spanish press reported freely on the situation, unlike the media in the warring countries, and so the outbreak became known as “Spanish flu”.

In August, the pandemic seemed to be receding – about 130m worldwide had been infected, and 200,000 had died. But in September, the virus mutated into something more deadly so that its victims drowned in their own sputum and blood which was choking their lungs.

This second wave began once more in the US – the first reports were from Camp Devens, near Boston – and again it travelled within weeks to mainland Europe on the vast troopships. The US lost 110,000 men during the First World War of which 45,000 died of flu of which 30,000 died without reaching the front, either on the suffocatingly crammed eight day crossing or in the hospitals beside the French ports.

Its arrival coincided with the armistice – the huge crowds kissing and hugging aiding its transmission.

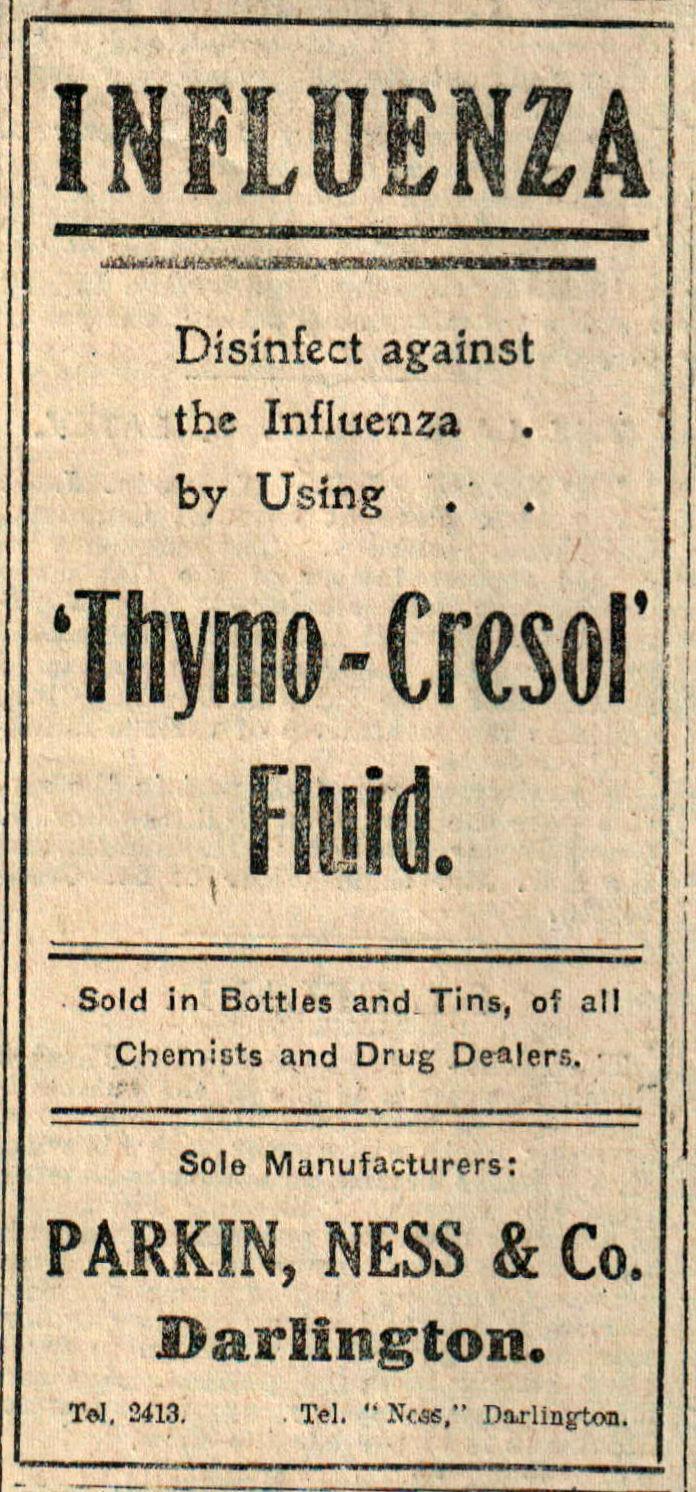

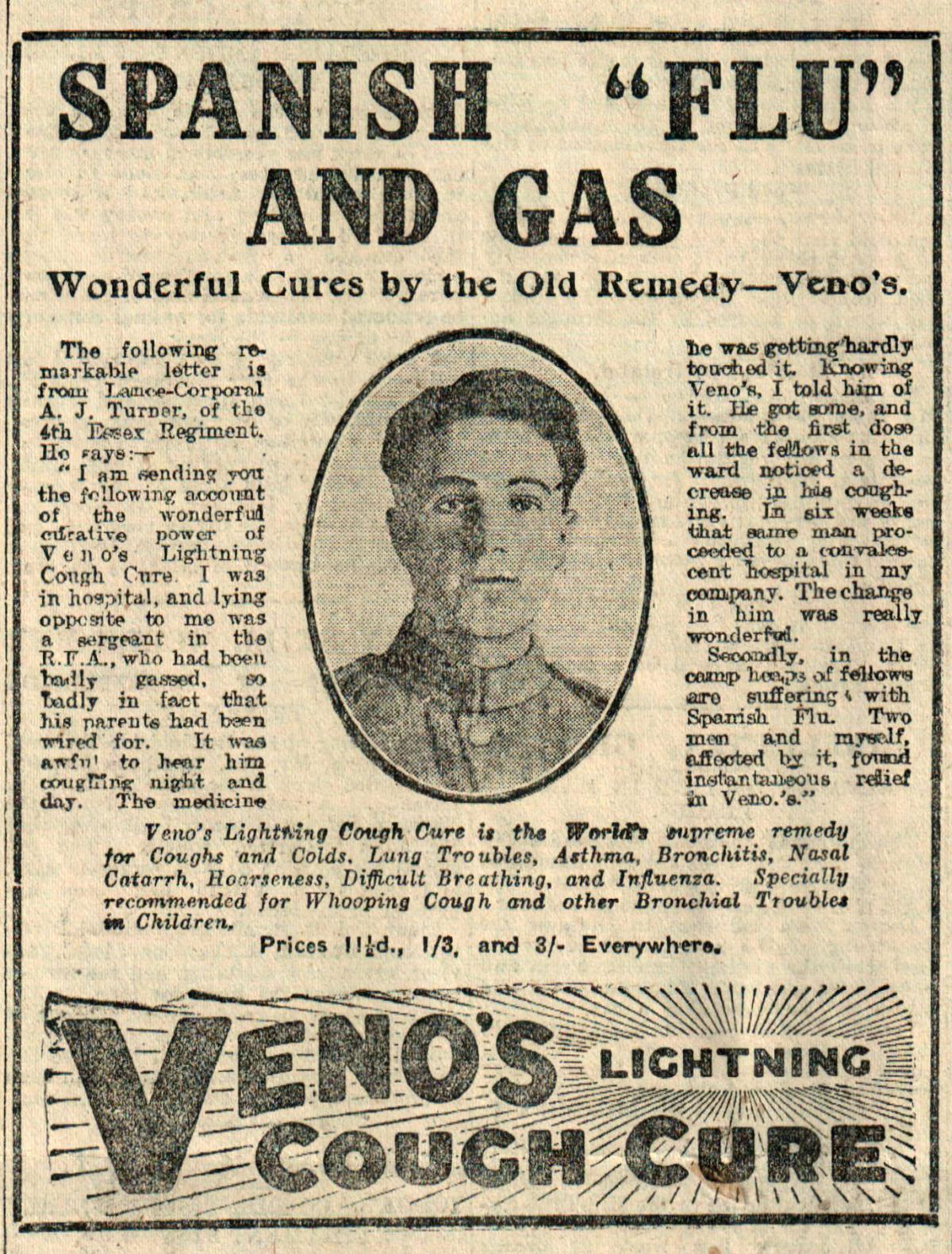

It peaked nationally in the last week of November when 5,100 people died across the country, including 51 in Stockton and 41 in Darlington, plus scores more deaths from Bishop Auckland to Guisborough. Although The Northern Echo of 100 years ago only reported the merest of details about the carnage in its midst, because of the wartime restrictions, you can feel the terror that gripped the area by looking at the adverts on its pages. From Parkin Ness’ Darlington-made “Thymo-Cresol Fluid” to Oxo which “fortifies the system”, there are many which are selling ways of avoiding the flu.

In Sunderland it seems to have peaked a week later, when 181 died of flu and 36 from its close associate, pneumonia.

“One very sad case is reported,” said the Northern Daily Mail’s reporter in Sunderland. “Upon the return home of the relatives from the funeral of a mother and two children, it was found that another child who had been left at home dangerously ill, had died.”

Theatres and schools were shut and political campaign meetings for the general election were cancelled, but even those measures could not save Mary and Charles Farrow who died during the peak of the pandemic in Gainford.

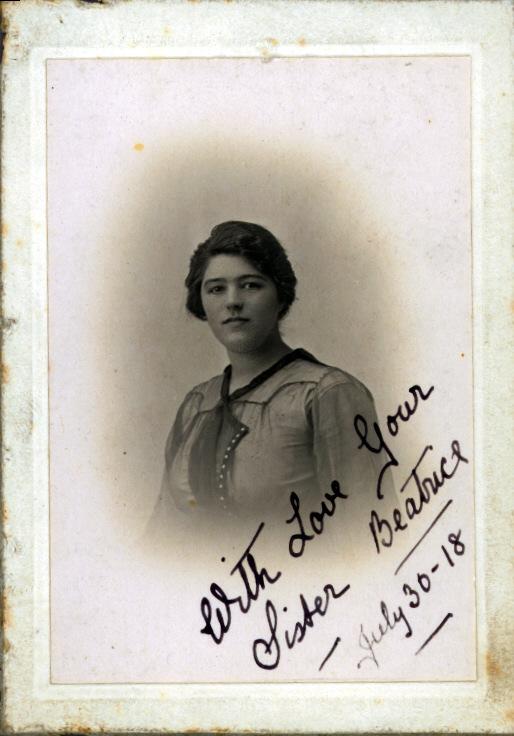

They had met in Hartlepool, where they’d grown up. Charles was a marine engineer and draughtsman and played rugby for Hartlepool Rovers and County Durham, and Mary (nee Lister) was the daughter of a ship-owning coal exporter. She attended Westwick Lodge School for Girls in Barnard Castle, graduated from Armstrong College in Newcastle (then part of Durham University) with a BA and went to Cherwell Hall Training College in Oxford (later part of Oxford University) to become a secondary school teacher. Her first job was at Chelmsford County High in Essex.

Charles joined up in September 1914, and so wasn’t with Mary on the morning of December 16, 1914, when she huddled in a neighbour’s cellar on Hartlepool’s Headland as three German warships bombarded the town. She even witnessed “an ugly black smoking mass”of a shell that destroyed the house next door, killing her female neighbour outright.

Mary and Charles appear to have been hastily married in Hartlepool on May 7, 1916, probably to fit in with his leave ahead of the great push on the Somme of that summer.

When Mary became pregnant, she gave up her teaching post and returned to the North-East to have her baby girl, who was born in early 1918.

With Charles, promoted to 2nd Lieutenant, away fighting, how she must have feared getting the dreaded telegram from the front telling her that her husband had been killed and their daughter would grow up fatherless.

But at 11am on November 11, 1918, those fears could be put away – Charles had survived the slaughter, and soon he was back in Mary’s arms, on leave.

They went to celebrate with Mary’s parents, who had a property in North Terrace, Gainford – which was where Mary died of the flu on November 25.

Seven days later, in the same address, Charles, who had spent the full four years of the war dodging death on the battlefield, passed away, another victim of the epidemic – although the military authorities needed some convincing that he had genuinely died and hadn’t just deserted once with the war over.

He was buried beneath the same white cross as his wife on December 4.

The flu continue to rage into the new year, but by February 1919, it was noticeably slowing. By the time it burned itself out in July 1919, it had killed anywhere between 50m and 100m people around the world – the war itself "only" killed 40m.

So there must have been countless stories similar to that of Mary and Charles, of people who had their lives stolen from them when they believed they had put the horrors of war behind them. And because they didn't die by the bullet or bomb, they are not recorded as war deaths – 2nd Lt Farrow, for instance, is not recorded on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website and doesn’t have a soldier’s headstone.

But at least the headstone he shares with Mary has been restored, and their story has been pieced together by Gillian Hunt, a civil servant in Darlington’s Department of Education offices, who has kindly shared it with us.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here