THE streets in the shadow of Bishop Auckland’s Asda superstore once contained the workshops and warehouses of colliery engineers Lingford, Gardiner and Company.

As recent Memories have told, the company was founded in Railway Street in 1861. It was a happy marriage of money from the Lingford family, of baking powder manufacturers, with the engineering nous of John Gardiner, who had been an apprentice to Timothy Hackworth at the Soho works in Shildon.

James Ewbank, of Shildon, began as an apprentice boilermaker there around the start of the First World War. His son, Denis, doesn’t know an awful lot about his father’s time there, although there are some fascinating snippets.

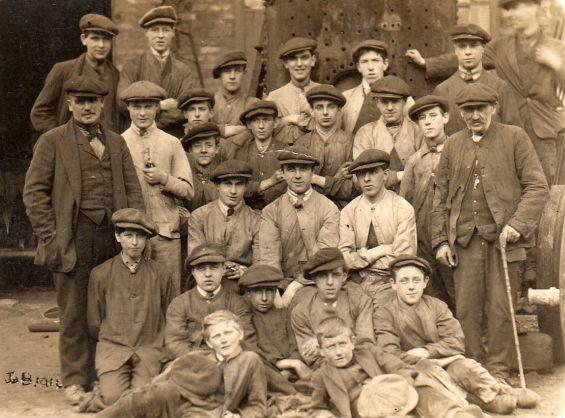

For example, these two photographs of the Lingford, Gardiner workforce have survived, as has the knowledge that during the war, James was despatched to the south coast to work on “the mystery towers”.

The secrecy-shrouded mystery towers – or “Project M-N” – were a remarkable attempt by the British to blockade the English Channel in the latter stages of the war. Up to 12 towers were to be sunk on the seabed from Dover to Cap Gris Nez near Boulogne with a steel anti-submarine net strung between them.

The towers would be armed, and have room for 90 men and submarine-detecting equipment inside them. When a U-boat was caught in their net, they’d have the capacity to destroy it.

Up to 8,000 people – including James – worked on this £12m project at Shoreham, on the south coast, near Brighton, although by Armistice Day in November 1918, only two of the 180ft tall towers were nearing completion.

The most complete tower eventually became the base for a navigation aid which still operates off the Isle of Wight, and the second was dismantled – it took nine months to bring it down, which is longer than it took to get it up.

James then returned to Lingford, Gardiner, where his career resumed its haziness. “I am sure that around 1931 he was on the dole,” says Denis, “which would probably be because Lingford, Gardiner had closed. I have no idea where he was next employed but he ended up at Shildon Wagon Works and was sent, along with many others, to the Browney Colliery railway disaster.”

This accident happened on January 5, 1946 – a memorial evensong to commemorate its 70th anniversary was held earlier this year in Durham Cathedral.

Near Sunderland Bridge on the East Coast Mainline, a goods train decoupled at the top of an incline. The engine and the front wagons went down to the bottom of the hill and were stopped at the Browney signalbox.

The decoupled wagons rolled down after them, and smashed into them, scattering wreckage across the tracks.

In the chaos, the signals on the mainline were not altered to warn of the danger ahead, and so the 11.15pm King’s Cross to Newcastle express, travelling at 50mph, ploughed into the wreckage. Its first five carriages telescoped into one another, killing ten people – mainly servicemen – and injuring 29.

The railway despatched all available hands, including James, to clear up the wreckage; the Durham Light Infantry sent 50 soldiers from Brancepeth Camp to help – one of whom, a 17-year-old, collapsed and died at the scene.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of “gawpers” turned up to rubberneck – so many, said the Echo, that the “ice cream vendors were busy”.

“My father said that one of the wagons had raw alcohol on it and some of the soldiers drank some of it with disastrous results,” says Denis. “He also found in the wreckage a book called The Last Journey, which was prophetic.”

Despite all the distractions, the men tidied the line in double quick time.

A circular letter survives from the Shildon works manager to James. It begins: “The work on clearing up the debris caused by the tragic accident at Browney has been dealt with in a remarkably efficient manner by all concerned, so much so that the lines have been liberated for normal traffic some 24 hours earlier than was at first anticipated.

“I wish to personally thank you for your share in this work, which has been undertaken under the most unpleasant and at time arduous conditions.”

Life in these heavy industries was not conducive to being long – James, a smoker like everyone else, was an oxyacetylene welder, and from Shoreham to Browney toiled in tough conditions. He died in 1955, aged 57, but left several fascinating insights into his work.

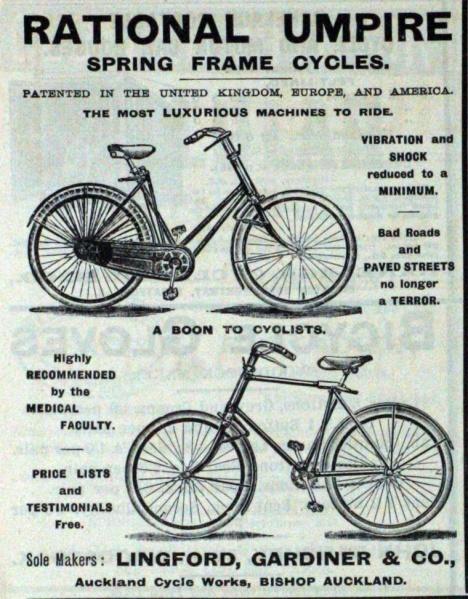

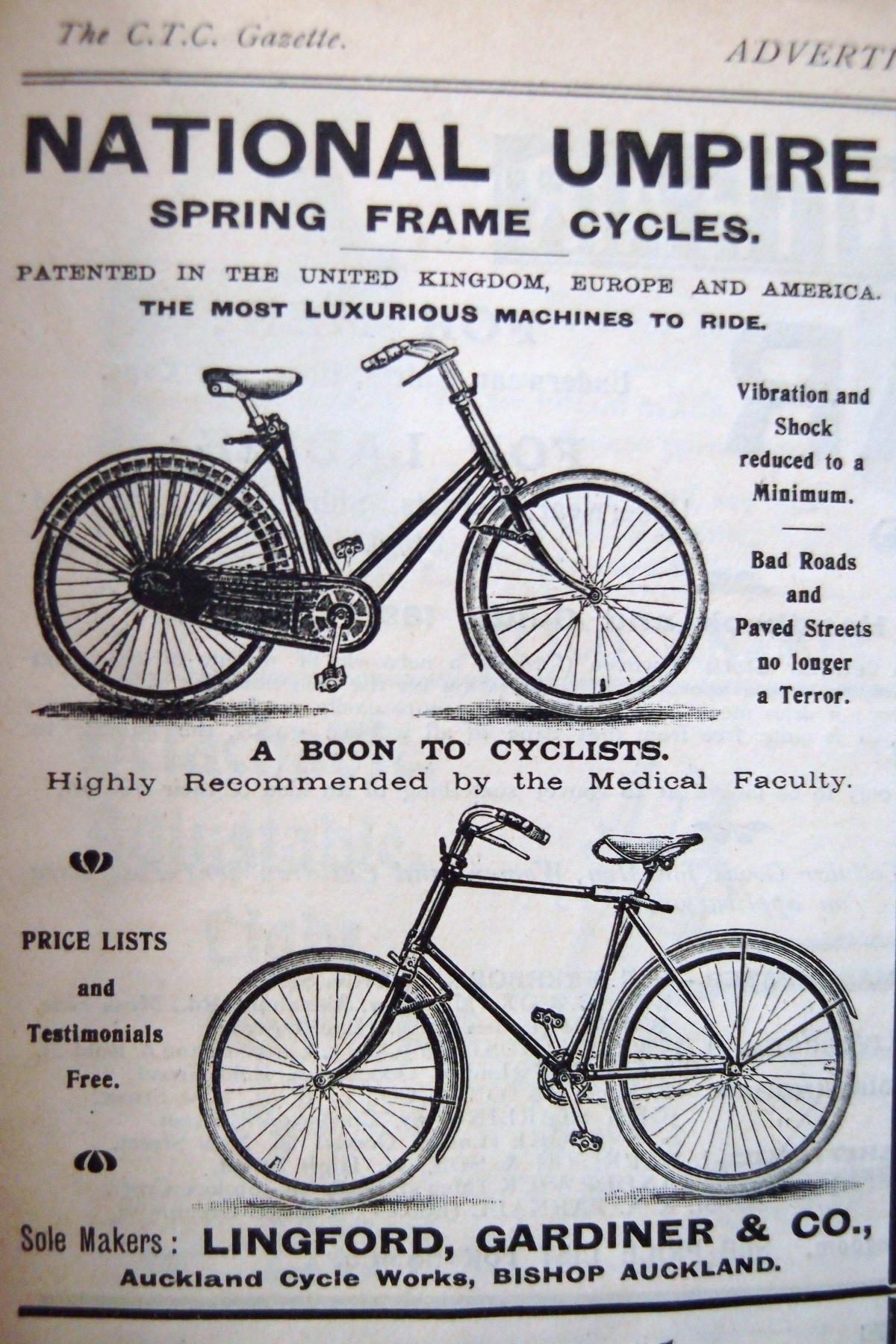

ONE of Lingford, Gardiner’s side lines was manufacturing bicycles in the 1890s and 1900s. These rejoiced in the brilliant, although inexplicable, name of Rational Umpire.

Keith Wade in Aycliffe wrote in: “I enjoyed the article regarding Lingford, Gardiner but I became suspicious of the brand name Rational Umpire, which didn't sound right somehow. I delved into my vintage bicycle collection and sure enough found an advert in the 1899 Cyclists’ Touring Club Gazette for the National Umpire spring-framed bicycles manufactured by the same company in Bishop Auckland.”

It has to be said that National Umpire is a little more likely yet all the other references we’ve ever seen are to the Rational Umpire.

Perhaps we’ll have to get in an umpire of our own to adjudicate.

KEITH’S mention of the Cyclists’ Touring Club opens up a new avenue of inquiry. The club – known as the CTC – was formed in Harrogate in 1878, and from 1887 handed out its seal of approval to establishments that catered for cyclists.

This came in the form of a cast iron plaque – later an enamel one – showing the club’s emblem of winged wheels.

Proud café and hotel owners would put the plaques on their properties.

How many of them remain today? Can you help? Please email their locations to us – chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk – or, even better, send us a picture. This is no wild goose chase – on its travels, Memories has spotted at least one CTC plaque that survives to this day. Please let us know…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here