“I WAS filled with pride in the thought that I was already in possession of the news of the day that the people still asleep in the dark, silent houses would not learn till breakfast time,” she said.

Emilie was the daughter of the editor The Northern Echo and the first female journalist to work on this paper. She became the first female reporter on the Daily Mail and the first woman’s editor on the Daily Telegraph in an extraordinary career that was featured last weekend in a Radio 4 play, the Sirens of Fleet Street.

Many thanks to everyone who has drawn the play to our attention.

Emilie reached Fleet Street from Larchfield Street where, in the shadow of St Augustine’s Church, she was born in March 1882. She was educated at home, immersed herself in her father’s review copies of the controversially fashionable “new women” novels – the chicklit of the day – and dreamed of becoming a journalist.

But in late Victorian times, women weren’t journalists. It was thought that they could not write, couldn’t do grammar, couldn’t understand the big issues and couldn’t dedicate themselves to a career.

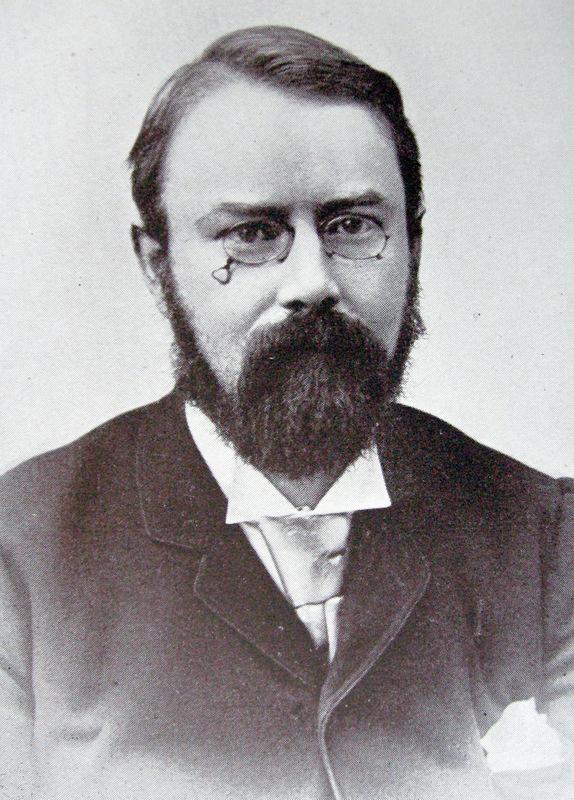

It certainly helped that her father, John, edited the Echo.

He was “a man of brilliant parts, a keen politician, and still more conspicuous as a writer”. A Tynesider and a devout Liberal, he joined the Echo in 1880, as a “breezy, racy struggled against prejudice in the church – at one ecclesiastical meeting, when a man spotted that she was a woman, she was forced to sit behind a red silken cord which meant she was officially non-existent.

WT Stead gave her a job on his new Daily Paper, but it closed after five weeks. She then became the first full-time reporter on the Daily Express, although at first she was not allowed to use the staff room.

At The Tribune, a newly-established Liberal paper, she became friendly with the Suffragettes – women, like Emmeline Pankhurst, who demanded the vote for women.

At Labour leader Keir Hardie’s suggestion, Emilie was in the House of Commons when he introduced a women’s suffrage resolution.

In the most patronising terms, other MPs filibustered his motion out of time, causing the Suffragettes to explode in rage in the gallery.

This was the first indication of the depth of their anger, and Emilie was the only journalist present.

As the Suffragette movement grew more violent, the Prime Minister, HH Asquith blocked Downing Street to keep the women protestors from his door. The Daily Mail employed Emilie as its first female reporter to cover the story, and she spotted a loophole in Royal Mail regulations which allowed women to be posted. At her instigation, the Suffragettes mailed themselves to 10 Downing Street, breaching the security, reaching the Prime Minister and gaining Emilie a great exclusive.

However, Emilie had a secret of her own: she had married Herbert Peacocke, a journalist on the Mail’s great rival, the Express. When her Mail bosses discovered this, they sacked her – she was sleeping with the enemy and, worst of all, liable to fall pregnant at any moment, which just proved how unsuitable women were as journalists.

During the First World War, Emilie had a daughter, Marguerite, and worked for the Ministry of Information, “writing articles celebrating the courage and resourcefulness of women”, according to her entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

Her husband, Herbert, fought in the trenches of the Western Front and was gassed at Ypres.

Although he returned, he was a shell of a man, dying in 1931, and Emilie had to support their family.

The Express took her on, and she covered Nancy Astor’s successful campaign in 1919 to become the first female MP to take her seat in th Commons.

Emilie moved to edit the Express’ women’s page. She had long railed against the inherent discrimination of a women’s page, but under her, the articles became broad enough to appeal to men as well. In 1928, the Daily Telegraph poached her to edit its new women’s section, and she stayed there until her retirement in 1940.

This radical pioneer, who pushed at the barriers that held women back and championed their causes, died in Kensington in 1964, but is still well-enough regarded in 2013 to have a radio programme reenact her life.

SO where did Emilie cycle to in those early hours of the morning when she was just a teenager?

She was born in 1882 at No 2, Larchfield Street, Darlington.

It was part of a terrace that was demolished in the 1980s to make way for the final stage of the town’s inner ring road.

The road was halted by a public inquiry, and now Buckden Court is on its site.

After a few years, the family moved to No 17, Langholm Crescent, and then in the 1890s to No 6 Victoria Road. It had formerly been the home of mayor Sir ED Walker, who has old people’s homes named after him, and was part of a grand terrace demolished in the 1960s for the first stage of the ring road. Now a block of flats and Sainsbury’s petrol station occupies the site.

The Marshalls moved to London from Victoria Road in 1902, so Emilie’s bike would have been parked outside the first house in the terrace on the right.

EMILIE’S mother, Mildred Hawkes, was the daughter of the editor of the Newcastle Chronicle. Mildred was politically active, being a leading light in the Darlington Liberal Association.

Mildred’s brother, Mervyn, stood for Hartlepool as a Liberal candidate in the 1886 General Election, but lost to a Tory by 1,000 votes. He told the story of his campaign in a well-regarded book, A Primrose Dame, but he died in 1890, aged 28.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here