A woman who once struggled to jog a mile has gone on to smash countless world records, beating many male athletes along the way. Ultra distance runner Sharon Gayter tells Lucy Richardson about her journey

HAD three thugs not decided to beat up a petite bus driver and steal her day’s takings, Sharon Gayter could still be ferrying passengers around east Cleveland instead of realising her dreams.

Rather than feeling bitter, she believes that everything happens for a reason, a philosophy that has helped her cope with thrilling success as well as the depths of despair when she once feared she might have to have a leg amputated.

The achievements of the British female number one who has held the ultra runner title for 13 consecutive years are staggering. She has covered more than 22,000 miles in more than 1,000 races including the world’s highest race, The High, across the Himalayan desert, reducing the outright course record by 11 hours. During the Badwater Ultramarathon, a gruelling 135 miles across Death Valley, billed as the hottest race on earth, she set the best time by any British athlete.

Sharon has run the 800 miles from Land’s End to John O’Groats taking more than 17 hours off the world record and pounded a treadmill for seven days at Teesside University where she broke the men’s record by almost 50 miles and sliced 100 miles off the female title. A few weeks ago, the 48-year-old ran the length of Ireland from Mizen Head to Malin Head to make history in a time of four days, one hour and 39 minutes.

Most people who reel off a list of jaw-dropping feats like this could be accused of boasting, but Sharon tells it in such a matter of fact way there is not a hint of arrogance – just passion, determination and an innate knowledge of how her physique works.

After growing up in Cambridge the shy and introverted twentysomething fell into a career with the civil service. The only person to speak to her at her desk ran to and from work and gave her a pair of trainers, which sparked her interest in running.

“I did not do sport at school, I couldn’t throw or catch a ball so I measured a mile around the block but I couldn’t run it at first. It took me three weeks,” she says. “People think you can naturally run, but I had to learn. When I ran that mile I at last felt a great sense of satisfaction.”

So she set herself the target of running the London Marathon which she finished in four hours and twenty- seven minutes, despite never having run further than 17 miles.

Her love of long distance hillwalking led her to becoming an endurance athlete and prompted her decision to change careers. “I drove around the country deciding where to live. I had to be able to afford a house and there had to be hills – the choice was between Middlesbrough and Carlisle, so I settled on Middlesbrough as it is drier.”

IT was through becoming a bus driver she met her future husband and fellow driver, Bill, and they married in colourful knitted jumpers at Gretna Green, three weeks after he proposed. “He always had eyes for me, but to me he was just another person to train with,”

she says with a smile. “Had three of Teesside’s finest not decided to beat me up to steal my takings I might not have gone to university. I wanted to learn about my sport and it helped me realise what I wanted to do in life.”

Now focused on becoming an ultra distance runner, she set herself goals that were more and more challenging, while learning how to maximise her body. She uses a technique calls periodisation where she does three weeks of progressively harder training covering 80, then 90, then 100 miles, followed by an “easy” week combined with speed work and repetitions.

“My mileage is much less now, but I have learnt to listen to my body,” explains the slight woman, who admits that chocolate is her only vice and enjoys a diet dominated by potatoes and custard.

One of her specialities has become running 24-hour races, yet the last four hours proved a mental hurdle. “I split them into four blocks, but after 20 hours the pain started, so I sat down with psychologists.

They asked whether I could pretend that I still had an extra four hours to go, which I couldn’t do, or could I break it down into four one-hour slots.

“After this my whole attitude changed, so at the next race after 20 miles I thought about having to run for one hour and it had to be fast, and I ended up winning,” explains the Teesside University sports scientist, who spoke at the campus in Middlesbrough as part of Universities Week 2012.

“Now the last four hours is the best four. I love the last six miles of a marathon as that’s when I win it and other people lose it.”

After years of success and relatively little injury her world came crashing down two weeks before the World Championships in 2010. What was thought to be a stress fracture in her leg was then suspected to be a bone tumour but, to Sharon, a hospital scan revealed an even worse prognosis.

“The specialist dropped a bombshell when he said in fact it was a cyst and there was nothing he could do with it,” she recalls. “The worst moment of my life was being told I would never run again. During the worst year of my life I thought I may have to have my leg amputated if the cyst could not be removed and I could become a blade runner. But I still had goals to achieve and I thought if I can run again I will do every race I can.”

Radical stem cell treatment saved her leg and swiftly put her back on the road to recovery. “I wanted to do a six-day road race in Athens and finish first, I beat the nearest man by 120km – that was some comeback year.

“I ‘chicked’ (outperformed male athletes) just about everyone,” she says with pride. “Anybody can achieve their goals as age is just a number. While I’m still ‘chicking’ the men, I will keep on going.”

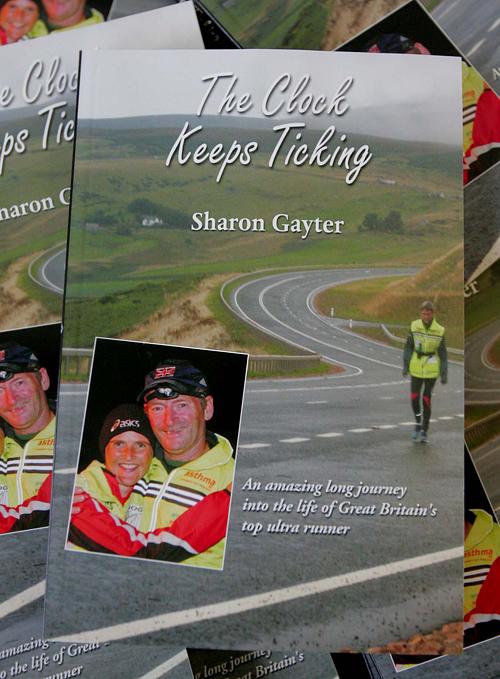

• The Clock Keeps Ticking, an autobiography by Sharon Gayter (Grosvenor House Publishing, £14.99) can be bought by visiting sharongayter.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here