Rachel Antill’s dramatic oil paintings capture the challenging environment of the wild and remote mountain ranges of the Himalayas. But the climber and artist tells Ruth Campbell how she gains inspiration from the ancient landscape which surrounds her home in the remote Yorkshire Dales

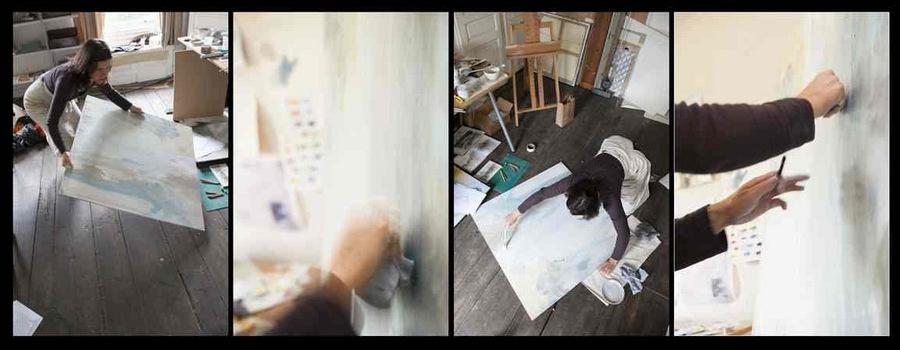

ARTIST Rachel Antill is working in oils, creating huge, abstract images of glacial crevasses, tumbling boulders and sheer rock faces. In her mind, she is back in the remote wilderness of Northern India.

Using sketches, watercolours and photographs from her challenging seven-week journey as expedition artist on a pioneering trek and climb in chillingly dangerous new territory, Rachel is attempting to capture the dynamic energy of this particularly majestic landscape in paint.

As she looks out of the window of her studio in her 18th century farmhouse in Swaledale in the Yorkshire Dales, the gentle, rolling countryside of Gunnerside couldn’t be more different.

Yet to Rachel, it provides the perfect inspiration.

“I love Swaledale. It is quite a raw landscape and keeps me in touch with the feelings of being in a different kind of wilderness. It would be harder to transport myself back in a city,” she says.

Rachel, whose love of the great outdoors was sparked by family walking holidays and who started climbing at the age of 16 when she joined the Venture Scouts in York, has now worked as artist on two particularly arduous climbing expeditions.

The most recent, exploring new routes in the rarely-visited East Karakoram Indian Himalayan range, involved crossing a dangerous and constantly shifting glacial landscape: “Everywhere you looked there was evidence of movement and change: the daily freeze and thaw, the continual sound of rock fall and avalanche, the tumble of boulders into crevasses, the groan of the glacier as it creaks and jolts.”

A part-time art teacher at Bootham School in York, she confesses: “There is an element of enjoying the more scary side of it and wanting to push myself physically.”

And the dangers are very real. On her first expedition, one group of 15 climbers four miles ahead of them on the route were all killed in an avalanche. A climber on a nearby summit also died.

“The mountains are unpredictable. Things can happen in the blink of an eye. You are never 100 per cent safe all the time. But I am very respectful of what can happen in the mountains, or in any wild environment.”

Her aim, she says, is try to capture in paint the effect landscape has on our understanding of our existence and purpose. “Our fascination with exploration is more than a drive to find what is there. We feel we can learn from it, about ourselves. Painting is the only way I can begin to explain the land’s dynamic energy and significance,” she says.

Her working conditions are not easy. On her first expedition, her oil paints went hard and white spirit wouldn’t work in the freezing temperatures, 5,000m up. “That was a huge learning curve. I had never tried to paint at such high altitude before.”

It is also physically demanding. “Trying to record how you experience the landscape seems like an impossible task. The wind fluttering the page you try to paint, the reflective light making you squint and the altitude sapping your motivation.

It’s overwhelming,” she says.

A highly skilled and experienced climber, Rachel’s work as an expedition artist combines two of her greatest passions. The daughter of horticulturalists, she did a foundation year at Greys School of Art in Aberdeen after leaving York Sixth Form College. But her love of climbing took over and she went on to work as an instructor in Scotland and the Lake District for five years before completing her Fine Art degree in Cardiff.

She specialised in ceramics at first, and found herself incorporating images of the mountains she climbed in her work. “I was more interested in what was on the surface of the pot than the pot itself,” she says.

It wasn’t until she arrived at Bootham School, about 14 years ago, that the head of art there, Richard Barnes, encouraged her to develop as a painter. “He has been my mentor and encouraged me to do more studio work,” she says.

As a result, she laughs, she is a bit of an artistic “mish-mash”. But her background in sculpture means she thinks three-dimensionally, giving her dramatic, sweeping paintings an added depth.

Her first experience as an expedition artist was in 2010, when she accompanied climbers Malcolm Bass and her partner Paul Figg to the Indian Garhwal with the objective of establishing a new route on the North West Face of Vasuki Parbat. “It was rather special, a big ordeal and a coveted prize in the climbing world,” she says.

More recently, in August last year, she set off again with Malcolm, Paul and others on an exploratory expedition to Eastern Karakoram, which aimed to reach the remote and seldom visited Rimo mountain group.

This time, she determined to capture the experience in film and photography, as well as paint. “My goal was to capture the atmosphere and uniqueness of this relatively unexplored area, to reflect the monumental scale and collective consciousness resting in centuries of ice,” says Rachel.

What made this expedition particularly unusual is that they travelled along the Siachen Glacier, in an area of disputed territory that has been the scene of Indo-Pakistan conflict for nearly 30 years. Their team, which included four British, were the first Europeans in 25 years given permission to explore this part of the mountains, close to the line of control between India and Pakistan.

Overcoming this hurdle was just the beginning.

The challenges of reaching, documenting and exploring the Rimo mountain group involved trekking through some of the most rugged, dangerous and previously unexplored glacial terrain in the Himalayas. “Many of the faces had not been climbed because of the remoteness. Not many people had ever been there,” says Rachel.

The route involved a dangerous crossing of the fast flowing Terong river.

From then on the whole expedition was on glaciers, which are changeable and constantly moving.

Crevasses suddenly open up and you are in constant danger.

Rachel, who was partly funded by the Arts Council on this trip, struggled, at times, with the ambitious technical demands of doing photography and film work in such conditions. If there was little sunlight, the solar chargers wouldn’t power her camera batteries. And fine grit in the air clogged up lenses and other equipment. “The hardest part was just keeping going with it all,” she says.

DURING the seven-week expedition, she would often go without a change of clothes for a week at a time. “There were small nods to hygiene,” she says. “You might get to steal a little bowl of water to wash your face if you were lucky.”

People always ask how she coped without a toilet.

“I was the only woman and they were all very good and respectful. But because of the crevasses you can’t be far away from others,” she says.

When she returns to Swaledale, it takes her time to process everything she has seen and experienced.

“I need to go through it all, assimilate everything.

I need a bit of distance,” she says. “First I start to make small paintings, they are just thoughts really.”

From there, Rachel progresses to large-scale paintings, which sell for up to £2,000. She has produced 20 from this expedition, and is planning more. The people who buy her modern, abstract work connect with it, she says: “They tend to get what it is all about. It is usually people who feel a connection with the landscape.”

Rachel has always enjoyed travel, having studied in Canada and explored Europe as a teenager.

“I think I am probably somebody who really enjoys very quiet, open spaces. The places you go to when climbing are completely remote, inaccessible.

She also paints in Scotland and the Lakes, as well as the scenery around her in Swaledale. “There are many quiet and unexplored areas on our doorstep that we shouldn’t underestimate in terms of their quality and uniqueness. What really inspires me is the feeling of oldness in Swaledale. You sit in the landscape and feel it has been like this for thousands of years.

“I am always taken aback by the unique quality of light and freshness of the landscape. It feels like returning to a quiet friend. The community, while small and dwindling, is incredibly supportive and friendly. You feel as if you belong somewhere here.”

- Rachel Antill is one of the artists taking part in the North Yorkshire Open Studios event, which offers the public the chance to see new work in the making, June 8/9 and June 15/16. www.nyos.org.uk

- Rachel Antill’s exhibition mountain shift will be open daily from May 26 to June, 21. Admission is free. The opening event will be at 11am on Sunday, May 26, at The Station, Richmond, and tickets will be available through the Swaledale Festival box office.

For more on Rachel Antill please visit: www.lightmove.co.uk Rachel’s sponsors included Montane Clothing and Swaledale Festival.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here