From living among remote tribes in Africa to being thrown in prison and working with deprived communities in the North-East, missionary nurse Ruth Deeth has lived an extraordinary life. But as Ruth Campbell discovers, one of her biggest challenges was marrying for the first time in her 60s.

RUTH Deeth remembers the fear and desperation she felt in her dark and dank cramped prison cell as if it were yesterday. She still shivers at the memory of her cell door rattling, as she wondered if this was the moment she was to be taken to her death.

It was 1975 and the missionary nurse didn’t know why she had been hauled off from the small bush hospital where she worked, near the Ugandan Kenyan border, by dictator Idi Amin’s men, and thrown in a dirty underground cell in the middle of the night.

She had been living in the hills and plains of Amudat for ten years by then and was aware that, after Amin’s military coup of 1971, people were shot in the street for minor infringements, such as not wearing Western clothes.

“I didn’t shine in prison, I wasn’t brave,” she says. “Two people had been arrested on trumped-up charges and condemned to death.

People were disappearing every day and bodies found floating in Lake Victoria. Even now, I can still feel the sensation as they rattled the door, opening the bolts and locks.

Ruth, who went on to set up a new community church in the Burbank area of Hartlepool and now lives in Ripon , North Yorkshire, still has the same precious copy of the Bible which sustained her through those dark, lonely hours.

Now in her 70s, but cheery and energetic, with a child-like enthusiasm for life, few of the new friends she has met at her patchwork and keep-fit classes in the city she retired to four years ago, would ever imagine what an adventurous life she led since she first went off to work as a missionary in her 20s.

WHERE Love Leads You, the book she has written about her life, charts her incredible journey. From Uganda, she went to Tanzania and Romania and eventually ended up working to help improve lives in a deprived urban area of the North-East.

Being a bit of a nomad herself, and impulsive by nature, Ruth thought nothing of packing her bags and heading off to wherever the Church sent her, whether that meant Tanzania, Leeds or Knaresborough, all places where she briefly made her home. Each move brought fresh challenges.

One of the biggest was possibly deciding to get married, for the first time, at the age of 61, a lifestyle change that came with its own trials.

Both Ruth and her husband, William, who was also marrying for the first time in his 60s, have had to learn how to adapt and compromise.

As we drink tea in the kitchen of their new home in a quiet cul-de-sac just behind Ripon Cathedral, Ruth touches the Africa-shaped pendant she wears round her neck. When she left, she says: “I felt a hole in my heart the shape of Africa.”

That was 20 years ago. but she still can’t get used to the choices we have in shops in England. “I don’t understand why there are so many varieties and makes of flour. I was used to just one in Africa. Flour is just flour.

“When I first went shopping here, I couldn’t cope. I would just walk out. There is too much choice.”

Having grown up in a Christian family who moved to South Africa from Blackpool in 1947, Ruth knew she wanted to be a missionary from the age of eight, although she confesses she was a particularly naughty schoolgirl.

“I had no doubt in my mind about what I was going to do. But I was always getting into all sorts of mischief, I was really naughty at school. The head said I had been to the school office more than any other child.

“I remember being put outside the classroom and I locked the door and locked them all in. I wasn’t malicious, just full of fun and nonsense.

I was always wanting to make people laugh. I have the same tendency now, but I do try to curb it,” she says.

It is a characteristic, however, that often came in useful in her life as a missionary.

Whilst living among remote nomadic tribes in Africa for about 25 years Ruth became used to working in basic surroundings, with few facilities, while having to contend with everything from tribal politics to political unrest.

During times of hardship, basic commodities like soap and cooking oil were scarce. The diet of the Pokot people consisted almost exclusively of milk and cows’ blood: “I never saw an overweight tribesman or woman,” says Ruth.

The young nurse from Blackpool was exposed to many unusual customs and superstitions, and tended to speak her mind. Ruth challenged the parents of young girls who arrived at her clinic, bleeding badly after being circumcised: “Such a senseless operation,” she says.

But she was sensitive to the culture of those she lived among and niggling questions kept her awake at night: “Were we wrong to encourage the girls to go to school and to discourage them from being circumcised? Was I making them outsiders? Could modern schooling and tribal customs mix?’

Even Christians would sacrifice goats when they were ill, rather than trust in hospital treatment completely. “It was so much part of their way of thinking that some diseases were the result of curses and needed traditional cures,” she says

Her forthright, upbeat character no doubt helped, too, during the three days she spent in prison, fearing for her life.

There had been months of anti-British propaganda on Ugandan radio before 12 officials and armed guards appeared and took her away. She was released, just as she had been arrested, suddenly and without explanation.

THROUGHOUT her ordeal, she continued to follow her set daily Bible readings, from the copy which now sits by her bed in her home in Ripon. While in prison, she was amazed to discover that the verses highlighted for those dates were about St Peter being arrested by King Herod and people praying for him before he was released by an angel.

“Tears poured down my cheeks. The reading was especially for me. I felt God was right there in my cell, comforting me,” says Ruth.

By this stage, unbeknown to Ruth, people all over the UK had heard of her plight and prayers were being said in churches all over the country for her. She made headline news.

She arrived back in London with little more than the clothes she stood up in. After spending some time in the UK, Ruth returned to Africa to work in a more advanced hospital in Tanzania, and helping to set up and administer a taped sermon service for people in remote communities.

Having ministered to the people in Uganda and Tanzania for 25 years, when she eventually arrived 20 years ago, aged 50, in Hartlepool, she found the people there a very different proposition.

Ruth was called to work in the run-down area of the town around the docks and was made a pastoral assistant at All Saints’ Church, Stranton, by the Bishop of Durham, David Jenkins, in 1991.

She found buildings boarded up in sad, neglected areas: “This was a different sort of deprivation to what I saw in Africa. Hartlepool had once been a bustling, thriving town. People were proud to be Hartlepudlians,” she says.

Not many people came to church, she says, and, unlike in Africa, she and her colleagues, who spent eight years establishing a community church in the Burbank area of the town, were often seen as ‘just another nuisance coming to the door,’ she says.

Some of her work even involved helping to get rid of poltergeists. Well known in the area, she would often be greeted by calls of ‘Ghostbuster!’ in the street.

Also, working nights in a nursing home, she made many friends and, after two years, she says: “I began to feel my heart becoming Hartlepoolshaped.”

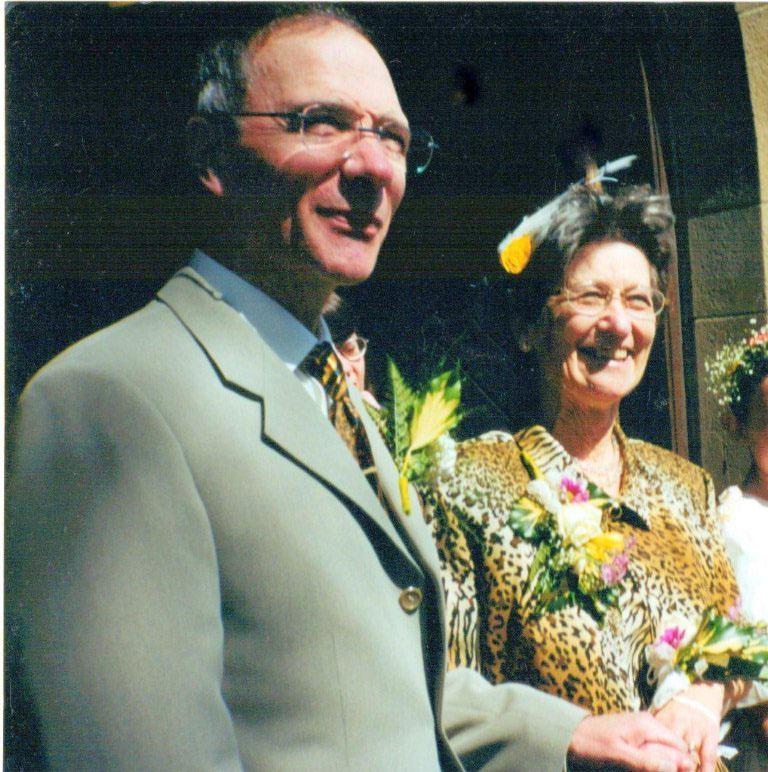

She met William, the bachelor vicar of Seahouses and former vicar of Byker and Morpeth, in 2000, after being introduced by a friend. “When he proposed, I said yes straight away,” she says.

His congregation let out a huge cheer when the news was announced and her brother described the ceremony, at All Saints in Hartlepool, as “the wedding of the century”.

Ruth enjoyed living in Seahouses, but it wasn’t easy merging the lives of two people in their 60s: “The first year was the hardest. I could no longer just fly headlong doing things the way I always had done,” she says.

“We had a prayer we prayed every night, about appreciating our weaknesses and strengths. At first it was difficult, but after our first wedding anniversary, married life became more and more enjoyable.”

When William was called to be a spiritual director to a clutch of churches in Yorkshire, they settled in Ripon. From here, Ruth also works as an esecretary, dealing with English language correspondence for a young colleague she worked with in her cassette ministry, who went on to become Bishop Mathayo Kasagara of Western Tanzania.

Who knows what adventures lie ahead? But, in the meantime, Ruth looks forward to taking things easier one day. “When I’m really old, I’m going to totter to a bench outside our door, sit in the sunshine, gaze at the cathedral and wave to the children from the nearby primary school as they pass by.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article