The proud son of a lifelong Teesside steelworker, PETER BARRON talks to a man who will have a unique perspective on today’s historic demolition of the Redcar blast furnace...

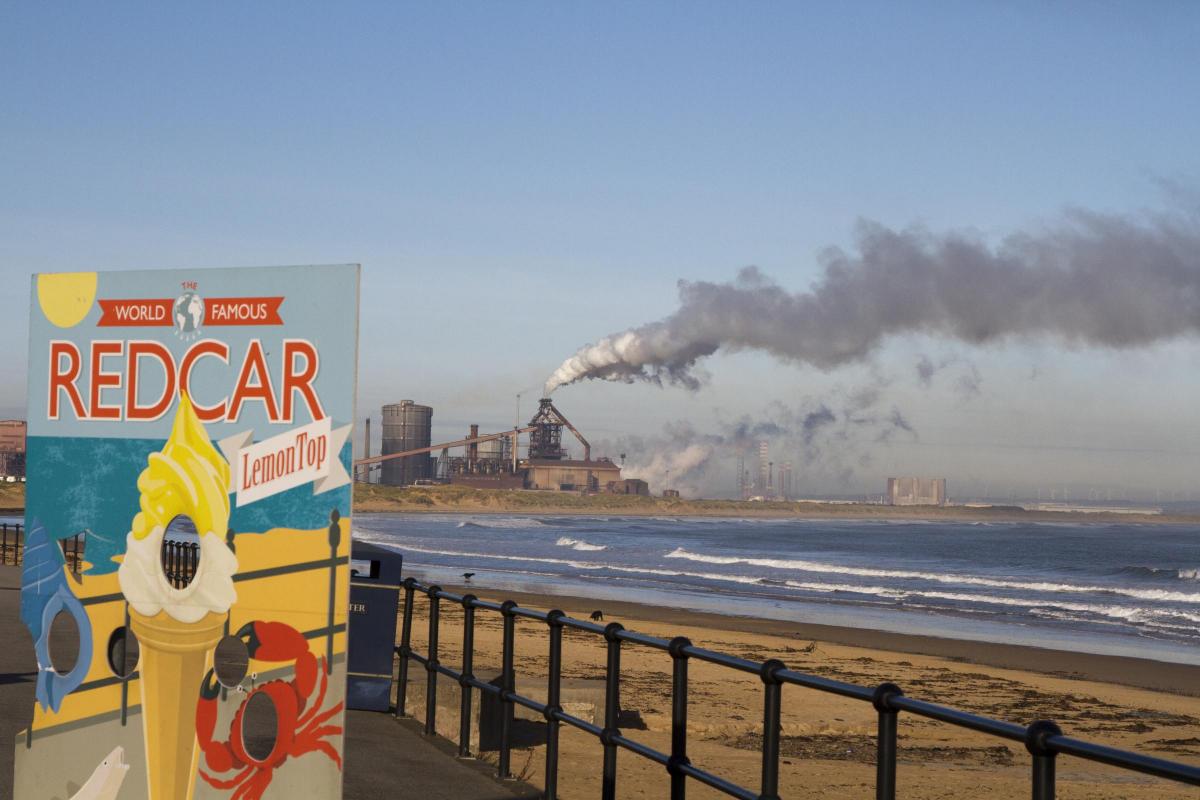

WHEN, at the flick of a switch, the Redcar blast furnace is razed to the ground today, transforming the skyline for ever, the thick clouds of black dust will symbolise the end of a way of life for generations of Teessiders.

And for one man, watching quietly from a vantage point somewhere nearby, it will be a particularly poignant moment because he was there as a young man when the flames were first lit, and it became his job to make sure they were safely extinguished.

Dave Cocks will be the most respectful of mourners. “I’m not sure exactly where I’ll be, but I’ll have to watch it come down because it’s closure for me,” he says, as we reminisce in the warmth of a seafront cafe. “Once that silhouette is no longer on the horizon, that’s it for me – the last physical link.”

As a 22-year-old Redcar lad, Dave joined Teesside’s army of steelworkers in 1978. A year later, he was part of the team that built the random structure that was to become the engine room of an industry then employing 31,000 men, including my own dad.

Only 1,700 were left when economic ill-winds forced the blast furnace to close on February 19, 2010, and it was Dave who was asked to lead the shutdown, using the unrivalled experience he'd gained while spending all of his working life in its shadow.

Hopes were fleetingly reignited when Thai steel firm, SSI, emerged as a potential saviour later that year, and Dave was asked to go back as a consultant while a deal was negotiated. SSI was given the keys in April, 2011, and the site resumed its operations in 2012, only to close again – this time for good – three years later.

Since then, once the wrangling with the Thai banks was over, the focus has been on reclaiming the site, with the Tees Valley Combined Authority aiming to breathe new life into “Teesworks” as Europe’s largest industrial zone for sustainable and low-carbon activity.

“Even now, whenever I drive down the Trunk Road, past the steelworks site, force of habit makes me look through the gaps to the blast furnace. In the days when it was working, I could always tell if everything was OK, but now it won’t be there and that’ll be sad.”

Dave’s ancestors have seen industries come and go before. His great-great-grandfather, Richard Tether, was a whaling captain, who sailed out of Hull and “knew the Arctic like the back of his hand”. Now, it is the rotten carcass of the blast furnace that stands, washed-up on the shore at South Gare, ready to be disposed of, once and for all.

Dave was born down the coast at Saltburn – Overdene maternity home, to be precise – just like me, and countless other Teesside kids. His dad, Charlie, had a variety of jobs, including serving in the RAF, working in the family's wrought iron business, acting as lighthouse watchkeeper, and shipping agent.

Throughout it all, Charlie volunteered on the Redcar lifeboat for 54 years, and it felt natural for his son to follow in his footsteps as soon as he was old enough.

Dave's only real break from a lifetime in Redcar came when he vanetured as far as Huddersfield to study for a degree in chemistry and bio-chemistry, emerging with a choice of job offers, and plumping for the British Steel Corporation, back home in his beloved Redcar.

As a graduate trainee, he did what was known down the works as “the milk round” – gaining experience in various departments – and, almost immediately, got involved with the newly-commissioned blast furnace. Standing 365 feet high, and with a hearth 14 metres in diameter, it was the biggest in the UK and equal in efficiency to anything in Europe.

“It was in the premier league of blast furnaces,” says Dave, glowing with pride over a cup of tea that’s gone cold amid the incoming tide of memories.

He goes on to explain how the hungry monster was fed cold, raw materials, containing iron ore, with coke piled in to produce the heat needed to create a chemical reaction. The result was iron, which was then converted into steel at the BOS (Basic Oxygen Steelmaking) plant.

The date the blast furnace began creating its precious by-product, back in 1979, is etched into Dave’s psyche. For years afterwards, October 12 was celebrated as its official birthday, with a workers’ party, and games of darts, at The Lobster pub nearby.

Some of the surviving blast furnace crew still get together for reunions. In the summer, it’s usually a walk at Saltburn, followed by fish and chips, and “making a bit of iron” – the steelworkers’ phrase for having a natter. In the winter, they gather down the pub, and this year’s reunion took place earlier this week, with an inevitable toast to days gone by.

“We were part of a massive family that went through tough times,” explains father-of-two Dave. “When things got hard, it was the spirit of that family that pulled is through. We prided ourselves on never being beaten – if something went wrong, we’d sort it. It was a battlefield mentality at times.”

In the end, the battle was lost, but Dave remains philosophical. These days, he’s a freelance first-aid instructor, mainly training workers from the renewables industry at the survival centre, across at Haverton Hill, and he’s optimistic about the future.

“I’m forward-thinking enough to realise that, after 150 years of steelmaking, it was a declining industry. If we can replace it with something that lasts another 150 years, it'll be progress.

“There’ll never be another industry that employs 31,000 people but, hopefully, we'll have lots of smaller industries to build up the numbers again.”

Dave, along with wife Liz, remains committed to Redcar. He's followed in his dad's footsteps as a lifeboat volunteer, so far clocking up 44 years, and taking over as chairman 18 months ago.

He's also a talented amateur photographer, with an impressive collection of pictures he’s taken of the Redcar skyline over the years. After today, a special one will hang on his study wall – it shows the sun, furnace red, setting behind the mighty blast furnace.

“We mustn’t forget our history, but we have to look to the future – and I guess that’s it out there,” he says, pointing through the café window to the North Sea.

Beneath a steel-grey sky, rows of shiny-white wind turbines stand like exuberant keep-fit enthusiasts at an aerobics class, making circular arm movements...full of energy.

It’s a new horizon.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here