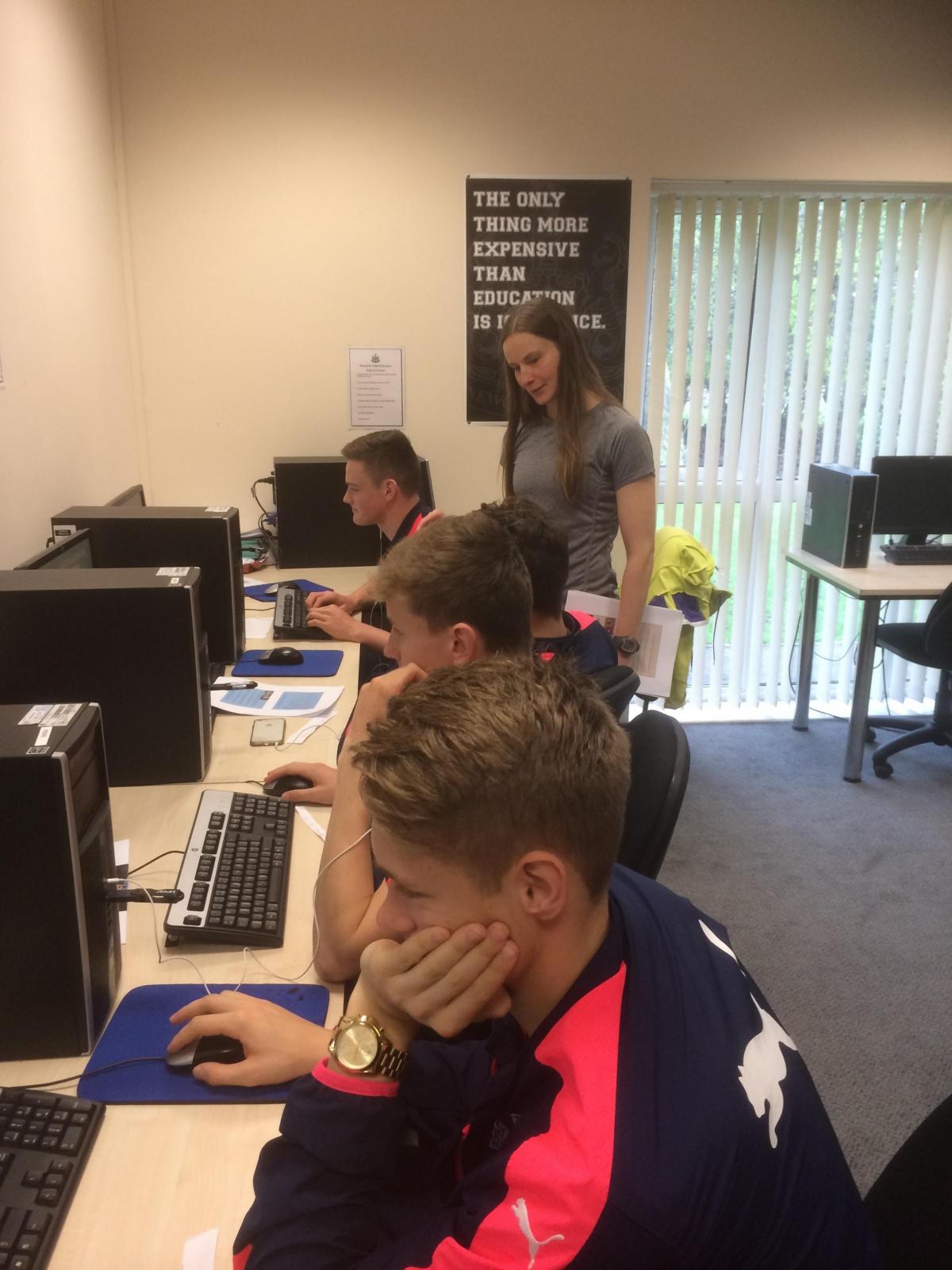

DOTTED on the four walls of the classroom at Newcastle United’s Little Benton academy are inspirational quotes, reminding youngsters that the time they spend there is not just about getting the ball out and scoring goals.

Clearly there is a desire and determination to develop first-team players of the future, but the academy system has a far greater responsibility than that. Yes, there is an attempt to produce footballers, but the aim is to develop individuals too.

It has been estimated by the Professional Footballers’ Association that around 700 players are released by their clubs at the end of most seasons. Of those who enter the game full-time aged 16, it is claimed 50 per cent will have left professional football two years down the line. By the age of 21, that figure becomes 75 per cent.

That is why football clubs across the country have a responsibility to educate, and there is stricter communication between clubs and schools.

“What we try to do is to make sure that no matter how much money a player gets, or what car they drive or how high they go in the game, that they remain grounded, humble,” said Darren Darwent, Newcastle United’s head of education.

“The kids are aware that we have a direct line with their teachers too, that puts them on their toes in the classroom with us and it means we can improve their behaviour. We are improving what they are like in the school as well by being on top of them.

“This last year was the best set of GCSE results we have had. I’m not saying it is down to us, but I like to think we play a role in keeping them grounded. We keep telling them they have X number of weeks until their GCSEs. We can add that pressure to them to make sure they give their best.”

It was recently revealed in a report that approaching 150 former professional footballers are now in prison, with the majority for drugs offences. A recent high profile case saw former Sunderland and England winger Adam Johnson being sentenced to six years behind bars for grooming and sexual activity with a girl aged 15.

Clearly, football clubs have a duty to look after the boys and girls wearing their club crest whenever they pull on a tracksuit or represent their club. There is a belief, Darwent says, and evidence suggests, that a child’s attitude in the classroom can be reflected in terms of their performance on the pitch.

Darwent, a former sports science teacher at Newcastle College, said: “We have had a Premier League ombudsman come in to look at our practices and we came out with flying colours – and that’s good to know. It’s good to know that what you are doing is right, even if you already believe it is.

“Like all Premier League and most Championship clubs now, we look at how to develop a child holistically. It’s not just about whether a kid has good talent on the pitch. It’s getting them to develop good manners, using their brain; that has to help them become a professional footballer too.

“Things have drastically moved on from just being a good footballer. Whatever we see inside this classroom, we see out there when they have a ball with them and what the coaches are seeing on the pitch. There is a link.”

Darwent has a small team working alongside him on the education front at Newcastle’s academy. George Scott is the education welfare officer, Jo Zoppi tutors across all age groups and Steve Common ensures course work is sent on time and looks after NVQs.

They have stuck messages on the wall for student footballers to look at, like ‘the only thing more expensive than education is ignorance’ and ‘education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.’

“After all, we have to have stringent exit strategies in place for them all to ensure that young footballers are helped when they are released by Newcastle because the reality is that plenty will be,” admitted Darwent.

Scott, the former deputy head teacher at a school in the west end of Newcastle who spent time on the books at Coventry and Watford, deals more with the schoolboys who are on day release rather than the full-time scholars.

He said: “When I came in full-time, having been in education for 30 odd years, the big thing was getting the education side organised. Parents wanted to be reassured that a boy’s education would not suffer when they came in. That’s our mantra across the board.

“We have sessions with them two afternoons a week. The under-13s and 14s come on a Monday and Wednesday afternoon and then we do the 15s and 16s on a Tuesday and Thursday afternoon.

“Our lads have to go to school on those mornings before they come here. We organise the transport for that. They are offered two afternoons but the schools or the parents might say they can’t come out for two afternoons, so we have to be flexible. The Year 10 and 11s are often more difficult because of their exams, although the majority are allowed out.”

The vast majority are from the North-East and Cumbria, but there are exceptions like one boy travels in from Whitby and another from the Scottish borders. Whoever they are, their schools receive regular feedback.

Scott said: “I have put in place a pastoral report which is done for every half term. That goes to the school and to the parent. They know we are looking after them. None of that is to do with football, but based on employability skills.

“We talk about them being punctual, prepared for work, getting on task, staying on task, listening to instructions, maybe being a leader, confidence, discipline, resilience, perseverance, sociability too. More so than ever before we are finding that whatever happens in the classroom is replicated on the football field. It’s maturity.

“The sport scientists we have here might ask what a player is like as well, they need to know if they can switch environments quickly. There might be one who is a nightmare in the gym, so we might advise what the best strategy is to deal with this lad. There is a work ethos, a respect ethos. We have a duty of care and we try to make them good people.”

There are 26 desktop computers for the footballers to work on when they are not in the fitness suite or on the pitch and the 16-18 year-olds work towards a BTEC diploma in sport, an NVQ apprenticeship as well as a Level 2 coaching badge. For those who have not attained a grade C in English or maths at GCSE level then they try to help them achieve that too.

Graduates of the academy programme at the Little Benton complex such as Paul Dummett, Steven Taylor, Sammy Ameobi, Adam Armstrong and Shane Ferguson have all gone through a similar route, although Darwent has introduced many changes since stricter guidelines were introduced.

Darwent said: “We have a lifestyle programme, so we have internet safety and guest speakers will come in to talk about mental health, how to handle money situations or other things. We have sexual health and drugs sessions through funding from the Premier League. They do little workshops with the lads.

“They judge themselves on where they will get with a football, but they should judge themselves on the person they become. A great advocate of that is Peter Beardsley, he is a tremendous ally for us. He is totally committed to the education side.

“When we want a progress report, and we might not see that much of them, we can pick up the phone to Peter and he will be down in five minutes. If that didn’t exist then sometimes we would be fighting against the tide.”

Whatever life lessons they learn, nothing will ever take away the experience of wearing the club crest. How many will become Premier League footballers? Who knows. At least there are methods in place to try to guide them in the right way even if they don’t.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here