IN a new book on the history of Irish football called Green Shoots, North-East based writer Michael Walker has included two sections on two Irishmen who each made a big impact on our region – Bill McCracken of Newcastle United and Johnny Crossan of Sunderland and Middlesbrough.

Walker was given access to some of McCracken’s private papers, including scouting reports. Having been a star player

for Newcastle for 19 years, McCracken later returned to St. James’ Park as a scout under Stan Seymour.

McCracken was the man behind the change in the offside law in 1925. Lesserknown was his early interest in a player who would become a Sunderland legend.

Crossan, 78, is still active in football in his native Derry.

Walker travelled to see him. There Crossan talked about his infamous transfer to Sunderland, his friendship with Brian Clough and, unlikely as it sounds, his keen interest in Yorkshire cricket.

BILL McCRACKEN

ON June 20, 1955, Bill McCracken, Newcastle United’s chief scout, wrote to the club secretary at St James’ Park, Edward ‘Teddy’ Hall, with a short list of names he was recommending for the following season.

The Newcastle manager, Stan Seymour, had already been made aware of these recommendations.

As well as John Bond, then a 22-year-old full-back with West Ham, and George Eastham, an 18-year-old inside forward with Irish League club Ards, McCracken earmarked two promising centre-halves.

One was Maurice Norman, a 21-year-old with Norwich City. Norman would go on to win the Double with Tottenham and play 23 times for England.

The other was an 18-year-old who had just broken into Millwall’s first XI, but who was already looking like a serious player. His name was

Charles Joseph Hurley.

For whatever reason, Newcastle United failed to act on McCracken’s Hurley tip-off – though they bought Eastham, of course, and made

a bid for Bond.

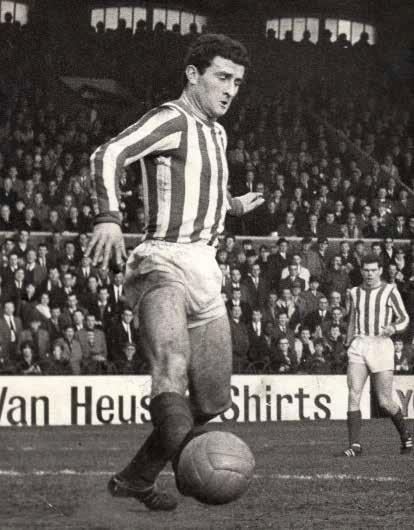

As we know now, just over two years later, Charlie Hurley left Millwall for Sunderland for £20,000 and stayed at Roker Park until 1969, making

401 appearances (one as a sub) and later being voted Sunderland’s player of the 20th Century.

The red-and-white legend could have been a black-and-white teenager.

This detail from McCracken’s private papers about Hurley and Newcastle

United’s interest will intrigue fans of both Newcastle and Sunderland, but it perhaps says more about McCracken.

Here is one of the most fascinating individuals British and Irish football has ever seen.

Born in Belfast on a street off the Falls Road, McCracken joined his local club Distillery as a teenager and apprentice joiner in one of the city

shipyards.

He made his Distillery debut on Christmas Day 1900. He was on his way to become a much bigger figure in the first century of football than even

Charlie Hurley.

McCracken was signed by Newcastle in May 1904.

Twelve months on, St James’ Park held its first ever League

Championship trophy. Two years on, there was a second and by the end of the decade, a third. Add five FA Cup finals between 1905 and 1911 and this was the club’s greatest-ever period, its greatest-ever team.

A cornerstone was McCracken. He was a defender, but that description

hardly does him justice. He was a thinker, a player who worked out from his Distillery debut that the offside law as it stood had plenty of space to

exploit.

McCracken became the master of the offside trap. When he first started playing, a player could be offside in his own half. A tactic was

to condense the play. In 1907 that was changed to only the opposition’s half. But it did not stop McCracken. He altered his game and became, as he said, “an overlapping wing-back before the term was invented”.

McCracken’s quick wit meant forwards kept falling for his trap. For this he was idolised on Tyneside and despised everywhere else.

Add his colourful personality and his willingness to join a confrontation, and he became the most infamous player in English football.

He was targeted by opposition supporters with missiles and once at Roker Park was hit by so many apples and oranges that he said the pitch “looked like the fruit market”.

At Stamford Bridge he was spat on, at Villa Park he was hit on the head

with a pipe, at Manchester City he sparked a pitch invasion.

An Ireland international, McCracken was banned from playing by the Irish Football Association for asking for the same wages his Newcastle

teammate, Colin Veitch, received from England. The ban lasted ten years.

Long after McCracken had retired from playing, the Manchester Guardian called him the “storm centre of his generation . . . the cause

of more demonstrations of hostility and resentment than any other player before or since”.

It was the offside trap which provided McCracken’s notoriety, and in 1925, a rule that had stood since 1886, was changed because, in large

measure, of his tactics. From 1925 onwards there needed to be two players behind the ball played forward, not three.

In theory this would make goalscoring easier and in season 1926-27 George Camsell scored 59 goals for Middlesbrough. The next season Dixie Dean scored 60 for Everton.

But one club resisted this tide of goals. They were Hull City and they had a new manager, Bill McCracken. After 19 years with Newcastle, McCracken left for management. He was to return to St James’ as a scout and, as his early identification of Charlie Hurley shows, he still knew a defender when he saw one.

JOHNNY CROSSAN

SITTING in a hotel in his native Derry, Johnny Crossan mentioned the Beatles, Fred Trueman, Patrice Lumumba and the Pope.

There were references to numerous footballers as well, from Alfredo Di Stefano to Brian Clough and George Best.

Crossan was reflecting on a career which did not seem captured even by the term 'unique'.

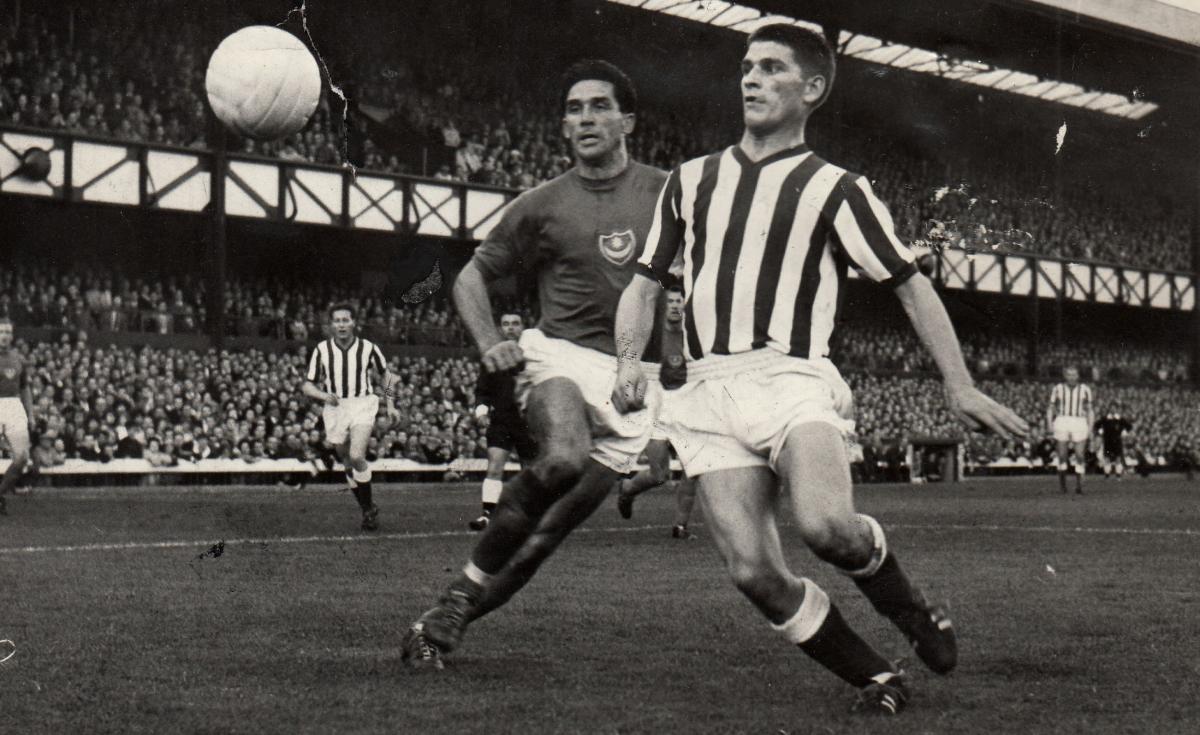

In the North-East, Crossan is known for his spells with Sunderland (1962-65) and with Middlesbrough (1967-70), but

the sprightly inside forward had a genuinely extraordinary career before those periods.

From the mid-1950s, when he was 16, until 1962, Crossan was at first a Derry City teenager, then a Coleraine player and then a Bristol City

signing. Only he wasn’t. Sunderland had tried to sign Crossan and the Irish FA found discrepancies in the proposed transfer. They reported

Crossan, the Bristol City deal was cancelled and he was banned from all football sine die – for ever.

He became as infamous as Bill McCracken and had to leave for Sparta Rotterdam to get a game. From there he joined Standard Liege, where

he marked Di Stefano in the semi-final of the European Cup.

After four years, Crossan’s ban was overturned and he at last joined Sunderland. There he became firm friends with Clough, the pair bonding over Yorkshire cricket. They went to see the Ashes series of 1964.

“At Old Trafford,” Crossan said, “we saw Bobby Simpson, captain of Australia, score 311.”

That’s around half the number of stories Johnny Crossan can tell.

Green Shoots, by Michael Walker is priced £20 and available on line from decoubertin.co.uk/greenshoots

Michael Walker has been a football reporter for over 25 years working for The Observer, Guardian, Irish Times, Independent and Daily Mail. Born in Belfast, Walker attended his first match in 1975 - Northern Ireland versus Yugoslavia at Windsor Park. He has reported regularly on both Irish International teams and has covered four World Cups and five European Championships. He has been based in the North-East for most of his career and continues to report on Sunderland, Newcastle United and Middlesbrough.

His book Up There is an examination of football in the North-East, how it came to matter so much and why it matters still despite a formidable lack of success.

http://www.decoubertin.co.uk/up-there-the-north-east-football-boom-bust-paperback/

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here