The arrest yesterday of a man allegedly responsible for a £1.3bn loss at Swiss bank UBS is just the latest in a string of high-profile rogue trader cases. Stuart Arnold reports.

IT’S unthinkable to most of us, but a few select individuals gamble with hundreds of millions – or even billions – of pounds every day. They are traders on the world’s financial markets, working for banks and other institutions, who with just a few phone calls or even the press of a keyboard key can make or break a company’s fiscal fortunes.

By and large, the public doesn’t get to hear about the vast majority of these deals. It is only when losses so huge as to be catastrophic are made – by those who don’t play by the rules – that they make the headlines.

They are the “rogue traders” – professional traders making unapproved financial transactions.

It’s a phrase that has slipped easily off the tongue ever since Nick Leeson hit the headlines in 1995 when he single-handedly destroyed the 233-year-old Barings Bank, which proudly counted the Queen as a client.

Notoriety and even a Hollywood film followed for perhaps still the most famous rogue trader.

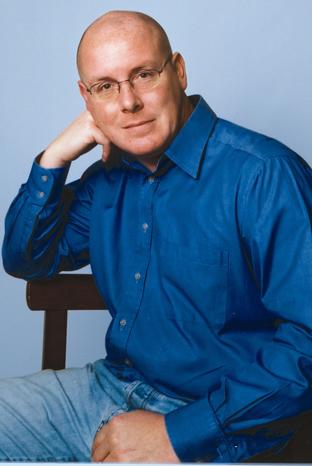

A Watford schoolboy-turned-City whizz kid, Leeson’s early career was a success, quickly making an impression with Barings and being promoted to the trading floor.

He was appointed manager of a new operation in futures markets on the Singapore Monetary Exchange (Simex) in the Far East and made millions for Barings by betting on the future direction of the Nikkei Index.

His problems began when he started making losses and set up a secret account to hide them.

Leeson began taking more risks to recoup his losses, but things soon spiralled out of control and he fled the country, leaving behind a devastating financial hole worth £827m and a note on his desk which simply said: “I’m sorry.’’ He was eventually arrested in Frankfurt, Germany, where he tried to fight an extradition warrant back to Singapore.

He failed and was sentenced to six and a half years by a Singapore court.

Leeson eventually wrote a book about his experiences, which became a Hollywood film starring Ewan McGregor and Anna Friel.

He has his own official website and is now a sought-after conference and after-dinner speaker around the world.

Like Leeson, others have also racked up huge losses on the financial markets.

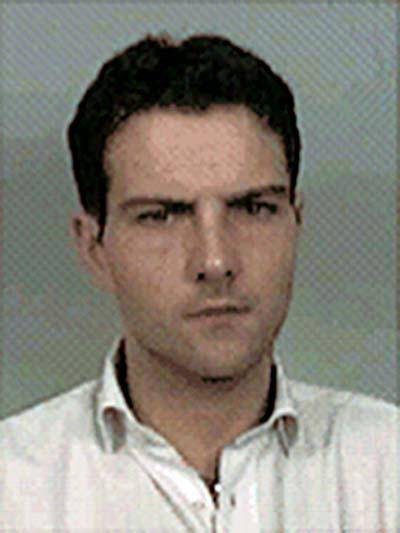

Last year Societe Generale trader Jerome Kerviel, from France, was convicted of being responsible for losing the bank about 4.9bn euros (£3.7bn), the biggest single amount of any rogue trader to date.

Kerviel also landed a book deal and in the book – Trapped in a Spiral: Memoirs of a Trader – said he believed the bank was happy with his work. At the trial, he also claimed the bank knew about the risk-taking.

The bank, in turn, said Kerviel, 34, made bets of up to 50bn euros (£43bn) – more than Soc- Gen’s total market value – on futures contracts on three European equity indices, and that he falsified offsetting transactions to mask the size of his bets.

Kerviel, who was born in Brittany, was sentenced last year to three years in prison, although he remains free because he has lodged an appeal. He is reportedly working as an IT technician in the Parisian suburbs. HIS moody Gallic good looks and story won him sympathy across France, with women wearing T-shirts with the slogan “Jerome Kerviel’s girlfriend”.

Another, bolstering his cult status, read: “Jerome Kerviel, 4,900,000,000 euros. Respect.”

John Rusnak, a currency trader at US bank Allfirst, based in Baltimore, Maryland, and then a subsidy of Allied Irish Bank, pleaded guilty in 2002 to fraud amounting to $691m (£345m).

Like Leeson, he came from a relatively humble background, a steel worker’s son who grew up in a suburb of Philadelphia.

He was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison for his crime, after doing a deal with prosecutors.

Toshihide Iguchi, a former car dealer, lost more than $1bn (£500m) at Japanese bank Daiwa, in fraudulent trading over 11 years from 1984 onwards. He claimed losses spiralled after he tried to cover up his initial bad bets.

Meanwhile, Yasuo Hamanaka, a trader at Sumitomo Corporation, one of Japan’s largest banks, lost the company $2.6bn in unrecorded copper market trades.

Known as “Mr Five Per Cent” or “Mr Copper” for the share of the global copper market he controlled, he was jailed for eight years for forgery and fraud in 1996.

The company paid about $150m to regulators as a result of the scandal.

And in one of Britain’s biggest banking scandals, 90,000 investors were left out of pocket after Morgan Grenfell fund manager Peter Young, who controlled £1.5bn of funds, broke City rules by investing in high-risk unlisted European securities.

He later appeared at City of London Magistrates’ Court wearing a woman’s jumper and dress, high heels and holding a pink handbag.

Young was eventually found unfit to stand trial.

So notoriety, cult status, book and film deals and even T-shirts with their name printed on them may await the person behind the £1.3bn UBS fallout.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here